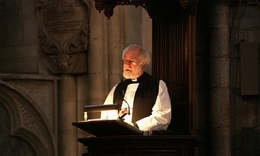

'Life has the last word': Archbishop pays tribute to Oscar Romero

© Westminster Abbey

© Westminster AbbeySunday 28th March 2010

A sermon given by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, at a service to mark the 30th anniversary of the martyrdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero, Westminster Abbey.Archbishop Oscar Romero is commemorated as a martyr in the Church of England's liturgical calendar on 24 March each year. His image is among ten statues of martyrs of the twentieth century placed over the Great West Doors of Westminster Abbey in 1998.

Read a transcript below, or click download on the right to listen [8Mb]

Sentir con la Iglesia: 'feeling with the Church'. This was Oscar Romero's motto as a bishop – you'll see it in many photographs inscribed on the episcopal mitre he wore. It is in fact an ancient phrase, very often used to express the ideal state of mind for a loyal Catholic Christian; indeed, it's usually been translated as 'thinking with the Church'. It can be used and has been used simply to mean having the same sentiments as the Church's teaching authority.

But the life and death of Monseñor Romero take us to a far deeper level of meaning. Here was a man who was by no means a temperamental revolutionary. For all his compassion and pastoral dedication, for all the intensity of his personal spirituality as a young priest and later as a bishop, he seems originally to have been one of those who would have interpreted sentir con la Iglesia essentially in terms of loyalty to the teaching and good order of the Church. And for all the affection he inspired, many remembered him in his earlier ministry as a priest who was a true friend to the poor - but also a friend of the rich. In the mordant phrase of one observer, 'His thinking was that the sheep and the wolves should eat from the same dish'.

His breakthrough into a more complete and more demanding vision came, of course, as a result of seeing at close quarters what the wolves were capable of, and so realising the responsibility of the shepherd in such a situation. The conversion that began with the vicious slaughter of innocent peasants by the Salvadorean National Guard in 1974 and 1975 came to its decisive climax with the murder of his Jesuit friend Rutilio Grande in March 1977, a few weeks after Romero's installation as Archbishop. From that moment on, sentir con la Iglesia had a new meaning and a deeply biblical one. 'The poor broke his heart', said Jon Sobrino, 'and the wound never closed.'

'Feeling with the Church' meant, more and more clearly, sharing the agony of Christ's Body, the Body that was being oppressed, raped, abused and crucified over and over again by one of the most ruthless governments in the western hemisphere. In the early summer of the same year, 1977, in the wake of the atrocities committed by government forces at Aguilares, he spoke to the people in plain terms: 'You are the image of the divine victim...You are Christ today, suffering in history'. These words were uttered in a town where the soldiers had shot open the tabernacle in the church and left the floor littered with consecrated hosts. There could be no more powerful a sign of what was going on in terms of the war of the state against the Body of Christ.

Romero knew that in this war the only weapons of the Body were non-violent ones, and he never spared his criticisms of those revolutionaries who resorted to terror and whose murderous internal factionalism and fighting were yet another wound in the suffering body of the people. For him the task of the church was not to be a subsidiary agency of any faction but to be the voice of that suffering body.

And so his question to all those who have the freedom to speak in the Church and for the Church is 'who do you really speak for?' But if we take seriously the underlying theme of his words and witness, that question is also, 'who do you really feel with?' Are you immersed in the real life of the Body, or is your life in Christ seen only as having the same sentiments as the powerful? Sentir con la Iglesia in the sense in which the mature Romero learned those words is what will teach you how to speak on behalf of the Body. And we must make no mistake about what this can entail: Romero knew that this kind of 'feeling with the Church' could only mean taking risks with and for the Body of Christ – so that, as he later put it, in words that are still shocking and sobering, it would be 'sad' if priests in such a context were not being killed alongside their flock. As of course they were in El Salvador, again and again in those nightmare years.

But he never suggests that speaking on behalf of the Body is the responsibility of a spiritual elite. He never dramatised the role of the priest so as to play down the responsibility of the people. If every priest and bishop were silenced, he said, 'each of you will have to be God's microphone. Each of you will have to be a messenger, a prophet. The Church will always exist as long as even one baptized person is alive.' Each part of the Body, because it shares the sufferings of the whole – and the hope and radiance of the whole – has authority to speak out of that common life in the crucified and risen Jesus.

So Romero's question and challenge is addressed to all of us, not only those who have the privilege of some sort of public megaphone for their voices. The Church is maintained in truth; and the whole Church has to be a community where truth is told about the abuses of power and the cries of the vulnerable. Once again, if we are serious about sentir con la Iglesia, we ask not only who we are speaking for but whose voice still needs to be heard, in the Church and in society at large. The questions here are as grave as they were thirty years ago. In Salvador itself, the methods of repression familiar in Romero's day were still common until very recently. We can at least celebrate the fact that the present head of state there has not only apologized for government collusion in Romero's murder but has also spoken boldly on behalf of those whose environment and livelihood are threatened by the rapacity of the mining companies, who are set on a new round of exploitation in Salvador and whose critics have been abducted and butchered just as so many were three decades back. The skies are not clear: our own Anglican bishop in Salvador was attacked ten days ago by unknown enemies; but the signs of hope are there, and the will to defend the poor and heal the wounds.

On once occasion when Monseñor Romero was returning from abroad, an official at the airport said loudly as he passed, 'There goes the truth'. It is hard to think of a better tribute to any Christian. If we believe that the Church is graced with the Spirit of Truth, we need to remember that this is not about a supernatural assurance that will tell us abstract truths: it is, according to Our Lord in the Gospel of John, a truth that 'convicts' – that exposes us to a divine presence, a light that will show us who we are and what the world is and where our values are adrift. The Church has to be truly the dwelling place of the Spirit by becoming a place where suffering and injustice are named for what they are. It may not make for a superficially placid Church; but only when truth about human pain is allowed an honest voice can there be healing for Church or world. The deepest unity of the Body is created by Christ's own embrace without reservation of the appalling suffering, the helplessness and voicelessness, the guilt, the frustration, the self-doubt of human beings, so as to infuse into it his own divine compassion. With Christ, said Romero in a Christmas sermon, 'God has injected himself into history'.

If that is the foundation for the unity of the Body, a true martyr-saint is someone who does not belong to a faction or party in the Church, who is not just a simple hero for left or right, but one who expresses clearly and decisively the embrace of Christ offered to all who suffer, who struggle, who fear to be lost and fear even more to be found. It is an embrace offered to all, including those who are trapped in their own violence and inhumanity: it is good news for the rich as well as the poor. But the embrace of Christ for the prosperous, let alone the violent, is not a matter of getting sheep and wolves to mingle freely; it is an embrace that fiercely lays hold on the sinner and will not let go until love has persuaded them to let go of their power and privilege.

That was the love out of which Monseñor Romero spoke in his last sermon when he urged the soldiers of the government to lay down their arms rather than obey unjust orders and commanded the rulers of El Salvador to stop the murder and repression. That was the love which provoked exactly what the love of our Lord provoked – that ultimate testimony to the emptiness and impotence of violent power that is murder. Organised evil has no final sanction except death; and when death is seen, accepted and undergone for the sake of the only true power in the universe, which is God's love, organized evil is helpless. It is exposed as having nothing to say or do, exposed as unreal, for all its horrific ingenuity and force. 'Life has the last word', said the great Gustavo Gutierrez preaching in 1995 in memory of the martyrs of El Salvador.

'Life has the last word' is a good text for Holy Week. Exactly thirty years ago today, the Requiem Mass for Monseñor Romero – a mass which was attended by people who are present here today – was interrupted by violence and overshadowed by more deaths. It must have seemed that the forces of death were still active and resourceful. So they were and are; yet the Mass itself embodies the truth that life is triumphant and active in the very heart of evil, betrayal, rejection and violence; it is the breaking of bread in the same night in which Jesus was given up to death, as our liturgies remind us. Today we give thanks for Oscar Romero's witness to life, the life of Christ in his Body; and, as we embark on Holy Week, we are left with the questions that Jesus puts to us again and again, in his own words, his death and resurrection, but also in the life and death of his saints and martyrs: 'Whose is the voice you speak with? Whose are the needs you speak for? What is the truth you embody?' Sentir con la Iglesia: can you – can we – make this more than an aspiration, so that we may 'gain Christ and be found in him'?

© Rowan Williams 2010