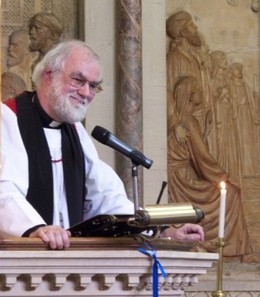

Archbishop commemorates 100th anniversary of the death of Florence Nightingale

Saturday 15th May 2010

The Archbishop preached at a service held in the chapel of St Thomas' Hospital by the Nightingale Fellowship in commemoration to mark the 100th anniversary of the death of Florence Nightingale.Read a transcript of the sermon below, or dlick download on the right to listen [14Mb]

The vision of the prophet in our first reading this afternoon has at its centre that extraordinary picture inviting us to 'lift our eyes' -- as our wonderful anthem also recalled for us -- to the heavens and see the multitude of the stars, and to think of a God who calls all the stars by name. To think, that is, of a love which is both universal and intensely particular, a love more comprehensive than we can begin to imagine and a love which, in each and every case, sees precisely and names exactly what is before it, a love which is clear, a love which is exact. To lift our eyes to the heavens as the prophet invites us to do is to be reminded of the challenge of God-like love - a love which has to be comprehensive and yet, at the same time, exact. A love that has to see clearly, that has to bring light into dark places.

No accident, then, that we are celebrating today a light-bringer: somebody who very literally brought light into dark places. But somebody who was also able to name with precision, with exactitude, the need and the suffering that was there before her. Someone who was able to see what others couldn't see or refused to see. Somebody who, in lifting her eyes to eternal love, at the same time focused her eyes on earthly suffering. It's quite a balancing act and the extraordinary character of Florence Nightingale lies very much in the way she held that balance. She reminds us all - as she reminded Victorian society - that love needs clear sight, that it isn't enough to say the right things, to make general noises. Love, if it was going to make a difference, had to be precise. And that is why the nursing training, the professional tradition that derives from her, is not simply a training in nursing skills but a training in seeing clearly. A trained nurse, in Florence Nightingale's vision, was somebody who could see, who was educated to see the particular, not to gloss it over, not to make it easy, but to see it as God sees the numberless stars; each face unique, each name special, and out of that to see what the needs are which love must serve.

It's often said, isn't it, that it's very easy to love humanity - the problem is human beings. And to love with clarity means of course loving human beings in their particularity and to cast light on the individual, the particular needs of this person, this patient, not to generalize but to attend, to look. Lift your eyes to the heavens, because that's the only way of focusing them on earth. Lift your eyes to endless, exact, intelligent love, the love that sustains everything - and something of that intelligent love will spill over into your own care, into your own devotion and attention. But of course that is as much as to say that caring changes you. Caring is not simply something you do: put on, put off, switch on, switch off. It changes you as a person. And one of the hardest challenges for anyone in the 'caring' professions is to know how to cope with that in ways that are not invasive and crippling or crushing; to let the reality of what is there change you and not to let it devour you.

And so to the NT lesson and to one rather odd feature of that lesson. St Matthew is showing us Jesus the healer. He tells us that vivid little story of Jesus' visit to Peter's home and Jesus noticing, seeing clearly, the problem with Peter's mother-in-law. We go on to hear of the healings he does on a larger scale with a bigger crowd. And the passage ends with a recollection of another piece of the prophecy of Isaiah: 'He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows'. But how very odd - because that prophecy is not about healing it's about identification. It's not a prophecy of a saviour who will come, wave his wand, cure people and go away; it's a prophecy of somebody who is alongside the needs of the people, who carries something with them. Care, changes; Jesus in his care, in his healing, is a Jesus who is himself vulnerable, who is moulded by the suffering, the pain that he himself engages with, that he heals. He is changed in his encounters. We read in another of the stories of healing about Jesus saying he felt that 'power had gone out of him'. He was changed by proximity to suffering.

So caring is about clear vision, realism, the clear sight of what's there, the refusal to turn away from the particular to the general; and because of that it's also about being changed in the encounter, having your heart and your mind stretched, growing up in and through the business of caring, in and through the encounter with suffering. All of this is part of Florence Nightingale's legacy. She was certainly a person changed by her encounter with suffering, a person who was in many ways a good example of the cost that comes with honest engagement. She was in many ways a phenomenally difficult woman - obstinate, self-righteous, generous, sacrificial, angular, judgmental, compassionate all at once, so much changed by the encounter with suffering that her life showed cost, damage even. The risks were real, and they still are. And yet in letting herself be changed, be in some ways almost moulded out of shape by the suffering she encountered, she made a difference that no one else could have made.

We can't any of us plan to be obnoxious, and angular and difficult – mostly we just are by nature. We can't plan to be difficult and unique saints. We manage normally to be rather average sinners. But we can look at someone like Florence Nightingale and think of the cost of attention. What did it cost her to see clearly, exactly, to see the specifics? How did it change her? Only because it changed her did it change the face of nursing care in Britain and far more widely. It may give us of course a little bit of patience with ourselves and one another, recognizing that sometimes things are only changed when they become more, not less, difficult. But above all she ought to remind us that it is quite simply possible, if your eyes are fixed on an uncompromising love, to see more clearly and then to love more exactly, possible to be changed, and changed in such a way that everything is changed around you.

We speak often of the saints as burning and shining lights in their generation. And as I've said that is an image very much at the heart of the mythology of Florence Nightingale. But, for all of us who seek to follow the calling of care, something of the same applies. We are all called to enlighten, to provide a perspective that will allow things to be seen clearly, all called to give that focused, specific attention which begins to give light to those most deeply in darkness because they feel they've been forgotten and never attended to.

We talk perhaps less often than we used to about nursing as a vocation. And that's a pity. Because a calling of any kind is a calling to be changed, not just a calling to do a job but a calling to grow into a certain kind of humanity. And generations upon generations of nurses responded to that call because - as much as anything - they wanted to be a certain kind of human being. It's my hope and prayer – and I trust the hope and prayer of many in this chapel this afternoon – that the nursing profession continues to be something that calls people who want to be a certain kind of human being, not just to do a job, not just to write things on lists, not just to contribute to some analysis of productivity and efficiency, but to be a kind of person, to be someone who sees with precision, who attends to the particular, and, in all of that, risks being changed. Not just caring from outside but being alongside; negotiating the great difficulties that brings, and keeping your own space, your own integrity and your own freedom, yet at the same time being generously open. No one pretends that that will be easy. But when it happens, when people do grow into that kind of humanity, things change. Light shines in dark places, other people's eyes are lifted and they discover something of that extraordinary promise at the end of the Old Testament lesson; 'they shall mount up on wings like eagles. They shall run and not grow weary.' Florence Nightingale like many another reformer ran fast and furiously to achieve her ends. She didn't always mind very much who she elbowed out of the way in the process, either. But, with that eagle eye of hers she saw what needed to be done, she did it; and she saw because she was changed by the love to which day after day she lifted her eyes.

© Rowan Williams 2010