How does God reveal himself? A Christian Perspective

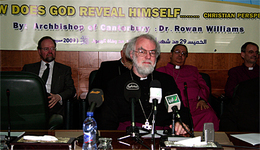

The Archbishop at the World Islamic Call Society campus

The Archbishop at the World Islamic Call Society campusThursday 29th January 2009

Lecture given by the Archbishop of Canterbury at the World Islamic Call Society Campus, Tripoli, Libya.The World Islamic Call Society is the world's foremost Islamic benevolent organisation with members from every corner of the globe. Its mandate is to work co-operatively with organisations, Muslim or non-Muslim, to serve the needs of humanity.

The lecture was hosted by Dr Mohammad Ahmed Al-Sharif (Secretary General of WICS) and attended by Most Revd Munir Anis (Bishop of Egypt), Rt Revd Bill Musk, WICS students and staff.

Read a transcript below, or click download on the right to listen [31Mb]

How does God reveal himself? A Christian Perspective

It is a great privilege to be asked to address this body, and I must begin with an expression of my sincere gratitude for your welcome and for the honour of being your guest.

It has been suggested that I speak to you about some of the ways in which Christians understand how God speaks to human beings. In what follows, I shall be speaking of how Jews, Christians and Muslims alike believe in a God who freely speaks to his people and so shows himself to be a God who cares for humankind. I intend to discuss briefly how Christians see the acts of God in the history of humankind and in the life of Jesus Christ, and also to examine how we think of our Jewish and Christian Scriptures. On the basis of this, I hope to draw out further some of the areas where Christians and Muslims find themselves speaking of similar things and where the differences remain to be examined.

Neither Christian nor Muslim thinks of God as a passive reality, waiting to be discovered by human beings. It is true of course that they will want to point to the various signs which God gives of his existence and his nature in the creation. Our own St Paul says at the beginning of his letter to the Church in Rome that 'since the creation of the world God's invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what he has made' (Rom. 1.20). St Paul is reminding his readers that the order and effectiveness of the processes of nature are part of God's loving provision of reminders of his presence and action – and that, therefore, no-one can complain that they have been left without evidence of God. Refusal to worship God as creator has no excuse, says St Paul; when the first human beings turned away from God, it was in the full light of God's gifts in the universe.

But since then, according to the Christian understanding, human hearts and minds have become dull. They have become accustomed to not seeing God in the natural order, because they inherit the distorted mind that resulted from the error and rebellion of Adam; we are not all guilty in the same way that Adam was, says St Paul, but we all inherit the results of his wrong choice (this is the often misunderstood doctrine of 'original sin'). Yet the gifts of God remain in the universe for us to see. And the Christian reader of the Qur'an recognises the same message about these things at many points. Sura 7.185 appeals to those who refuse the message: 'Have they not contemplated the realm of the heavens and the earth and all that God created, and that the end of their time might be near?' And the same is said in Sura 13.4: after a description of the order of the heavens and the variety of provision for human needs in the environment on earth, it is said, 'there truly are signs in this for people who reason'. Many more texts in both Christian and Muslim Scripture could be quoted.

Yet this is not the whole of what we say. God has made the world to display something of his nature and his power, but he also speaks through his witnesses in history. So for St Paul, the habitual ignorance of human beings as a result of the betrayal and fall of the first human beings has to be addressed first by the giving of the Law to Moses. But sadly, this Law has itself become – against God's purpose – another means by which human beings try to get beyond their dependence on God, so that they imagine they can make themselves pleasing to God simply by their own efforts. So God acts once again to overcome this new error and rebellion. He acts in history to open the door to a new possibility for human beings , and he does so in the person of Jesus Christ.

Thus God always seeks to make himself known. God knows that when we fail to see him and know him, we condemn ourselves to a darkness of spirit that means we never become what God wants us to be. So he desires to bring light into that darkness – not only for the sake of human beings but for the good of all creation. In the eighth chapter of the same Letter to the Romans, Paul says that the whole of the creation is held back from becoming what God wants it to be by the failure and sin of human beings – so that when this is overcome, there is a foretaste of the glory of God appearing in everything that has been made. Revelation is the beginning of the restoration of all things in the universe to their proper condition. And so Christians will speak of Jesus as the beginning of a 'new creation'. St Paul in another letter writes about how all things hold together in Jesus. And because it is through Jesus that the creation is brought to its new condition, the condition in which it is set free to become what God made it to be, the early Christians concluded that creation had always held together because of the eternal Word of God which was embodied in Jesus. Jesus' life came to be understood as the translation into human terms of an everlasting dimension in the life of the one God – the eternal outpouring of divine love and its reflection back to the heart of God, the movement outwards and then back into the depth of divinity that allows us to speak of God 'the Son', though not in any material or literalistic sense.

So we do not say that Jesus 'becomes' divine, or that he adds something to God. He is simply the human form of the eternal Word which, says St John in his gospel, is always 'in relation to' the God who is the source of all things. When we as Christian believers identify ourselves with him in the ritual of baptism, we are made able by the gift of the divine Spirit to call God 'Father' just as Jesus does. In other words, God makes himself known to the believer not by telling us new information about himself, and not even or not only by revealing a law, but by making us able to enter into a relationship with him in which we have confidence and intimacy – like the intimate relationship that a child has to a parent.

When Christians speak of God making himself known, they mean that God, in addition to the signs he spreads abroad in creation and in addition to the revelation to Moses of the Law for his people, makes himself known as a loving father to us. Because Jesus in the gospels prays to God as father, and because we believe that he is more intimate that any other with God, we understand that when we are made able to pray in his words, we are brought as close to God in love as we can be. And because we also believe that Jesus perfectly expresses the one unchanging will of God, we know that in Jesus' life and death and rising from the dead we encounter a God whose purpose is always love and forgiveness. It is the whole life of Jesus that is the revelation, not only his teaching.

This may sound very different in many ways from what Muslims believe about the way God makes himself known. But let us think for a moment about some of the things in common – because they are in fact very significant. First, we both believe in a God who freely creates the world and sets it in order and adorns it with beauty, so that human minds may see the signs of his power and grace and loveliness in what he has made. They believe in a God who wishes to be known, since he has made human beings to find peace and joy in knowing him. They believe in a God who not only shows signs of his power in creation but also tells us what his will and purpose is for us: he shows us what kind of life we must lead in order to be at peace with him – a life of justice and truthfulness, mercy and self-control, a life in which we do not follow our selfish instincts all the time but learn to live in a community where all are treated with fairness and compassion. This is the pattern spelled out in the Jewish Law, in the Christian Scriptures and in the Qur'an. And even more than this, they believe in a God who speaks in appropriate language. It is a special feature of the Qur'an that more than once it insists that God has given the Qur'an in Arabic, so that no-one can say that it is obscure or foreign (Sura 41.44); God has spoken in a language that Muhammad's contemporaries can hear as their own (Suras 42, 43 and 44), and this is a testimony to his mercy and his willingness to communicate with us. For Christians, this is not expressed in the same terms; but the same belief comes through. God speaks in our own language – the language of human beings who suffer and struggle and endure trials. Jesus is identified completely with human beings so that no-one can say that he speaks as a 'foreigner' to human experience. He even endures the experience of being tested by God through suffering and mental struggle, so that we can recognise that he truly speaks out of a human heart and mind, even when he speaks divine truths (this is the theme of much of the anonymous Letter to the Hebrews, as for example in 2.10, 14,18, 5.7-9 and elsewhere).

Thus we can say that Muslims and Christians share the conviction that because God in his compassion freely chooses to communicate with human beings, he also chooses to address them in appropriate ways so that they may understand – and also so that we may be confident that God understands us and knows us better than we know ourselves. In both our faiths, there is a conviction that only when we hear God speaking do we really come to know not only who God is but who we are; so that in our obedient response to what God says, we become more fully what God made us to be. As I have already noted, Christian Scripture also says that the whole world becomes more truly itself when men and women are in harmony with the will of God, and it would be interesting to discuss further what if anything in Islam corresponds to this idea. But the most important thing is that revelation not only tells us specific things about what God wants but also tells us that God is a God who cares about us and knows us, and that we are never absent from his presence; never absent therefore from both his judgement and his love or mercy.

What then for Christians is the role of Scripture? Because of the considerations already outlined, Christians do not regard written Scripture itself as the primary source of revelation. God makes himself known in the entire life of Jesus, including his death and resurrection, and calls men and women into relationship with himself through the gift of the Hoy Spirit. The first generation of Christians used the sacred writings of the Jewish people as the only Scripture they had, although at the same time writings were being produced which were to become the distinctively Christian Scripture of the New Testament. In the Jewish Scriptures, revelation first happens in and through events like the delivery of the Hebrews from slavery by the hand of Moses, and the giving of the Law to Moses is only to be understood in the light of this event (compare Sura 7 of the Qur'an). The witness of the prophets of the Hebrew Scriptures is in the nature of a call back to loyalty to the patterns of justice and mercy laid down in the Law of Moses. The history of the Hebrew Kingdoms is part of the revelation because it shows the alternation of obedience to God and disobedience, so that the reader understands more and more fully what the Law implies. So in Christian Scripture, what we see is the telling of the story of Jesus, followed by the reflections of the first Christian generation, especially those who were Jesus' immediate followers or the hearers of those first followers. The purpose of Scripture is to make us today contemporary with the events of Jesus' life and to open us up further to the Spirit who makes us more and more like him in our life together.

So Scripture is 'inspired' not because it is directly spoken by God but because it is used by God as part of the work of the Holy Spirit in bringing us into relationship with Jesus. Human writers are used by the Spirit to speak the words that will bring Jesus' presence clearly before us – in the accounts of his life and in the accounts of the experience of the people closest to him. Everything else Christians say has to be tested by the standards of what Scripture says, because it is the first and most direct witness to Jesus. For many Christians, this means that any teaching not directly present in Scripture is to be rejected; but for the majority of the historic churches, there is a tradition of interpreting Scripture which allows more development from the words of Scripture alone and the introduction of teachings not explicit in the Bible. Even in that case, however, Christians would deny that anything can be added that is in contradiction to Scripture.

Muslims sometimes find it puzzling that Christians use a scripture that is written in a variety of styles and genres by a large number of human authors during a period extending over a thousand years. Christians on the other hand sometimes have a view that the Qur'an is a somewhat monochrome document of law and instruction. Muslims may wonder whether there is any coherence in the Jewish-Christian Bible, and Christians may conclude that there is no proper history behind the Qur'an. Both would be mistaken. The Bible is understood by Christians to be the record of a single story unfolding over the long history of God's dealings with the world and reaching its climax in the life of Jesus, which has been prepared for beforehand by prophecy and other kind of foreshadowing in the events and persons of the history of the Hebrew peoples. Its divine origin is thought of not simply in terms of God directly controlling its composition or even guaranteeing the absolute historical truth of every portion but in relation to the unity of witness to God that is there to be traced in the changes and chances of history. God is understood as speaking first through his activity in this long history, and it is this to which Scripture bears witness. St Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth Christian century writes of Scripture as the record of the persons in whom revelation reaches us. But the Christian needs to recognise the importance of history for the Qur'an also: here too there is a strong sense of God's consistency in history, with appeals constantly made to the pattern of God's dealings with many of the same figures that Jews and Christians speak of – Joseph and Moses, not to mention Mary and Jesus. There remains a serious difference of emphasis in how Scripture is understood, since the Qur'an is written throughout in the voice of the Creator and the Bible is not. But it is important to see that the contrast is not necessarily just between a faith that understands revelation as taking place through human history and a faith that understands it as taking place through a single text in isolation.

However, the most important point of convergence remains the belief that God wills to communicate, that God is a God who speaks and whose will to speak with us is grounded in his disposition to mercy. Christians and Muslims alike believe that they have been invited by God into relation with him, according to his own free decision. And this means that they are both inevitably missionary religions, in the sense that they believe they have been given a gift that must be shared, and shared with all. Neither of our faiths can be content with a merely local or ethnic base for faith; we believe that God has a purpose for all human beings, in a unified community of justice and mercy, a community where the needy are not forgotten, as our Scriptures say, and the hope of the poor is not taken away – a crucial challenge in our present time of economic anxiety when many pressures might so easily combine to take away the hope of the poor. In this area we can certainly work more closely together, especially in Africa, where it would be a tragedy if our differing understandings led us to forget the extreme human need that faces so many and which cannot be relieved by the actions of one set of believers alone.

Yet the fact that we are both missionary faiths with a universal vision of justice also means that we are not likely to come quickly to a full accord. Our understandings of revelation are, as I have suggested, very close in many ways, yet they diverge sharply over the question of the status of Jesus and thus over the nature of the relationship with God that we Christians believe becomes available through Jesus and the Spirit. It is right that we continually seek to grasp more fully and intelligently what one another is saying and move away from distortions; and it is right that we find ways of working together in the face of anti-religious pressure and indifference to the claims of justice and the needs of the suffering. Yet we shall still have a debate in which to engage.

What matters then is our resolve to debate only with intelligence, and with gratitude for the good things we see in one another. And it also matters greatly that, when we seek to persuade people of the truth of the gift that we have received, we should resolve not to use false or violent inducements, not to say or believe the worst of one another, not to punish people for the conclusions they come to in good faith. This is, I realise, an audience committed to proclaiming the truth of Islam and the final authority of the Qur'an, because of the conviction that this is the gift God has given, in its fullest form. As a Christian, I am bound to proclaim the offer of forgiveness and transformation made in and through the Person of Jesus as the supreme embodiment of God's eternal love. For us, 'love casts out fear', as the Apostle St John says, so that no-one should be compelled into belief out of fear. For you, 'there is no compulsion in religion', as is said in the Qur'an. If we both believe in an all-powerful God who wills to communicate with his people on earth, we ought to be free from the anxiety that drives people to enforce their beliefs through brutality and assault – as if God depended on our violence for his Word to prevail. Both our histories have long shadows on them in this respect; but our own age, with all its renewed and in many ways worsened problems of tension between religious extremists, has also been an age in which Christians and Muslims have learned more about one another than they have for centuries and have identified once again the words and thoughts that enable us to speak to one another as kinsmen, not as complete strangers. My prayer is that today's will, by God's grace, be one small part of that learning from one another – even one small part of what God wills to be said and known in the world he has made in his power and glory and love.

© Rowan Williams 2009