Archbishop: 'What's the martyr's message to our society?'

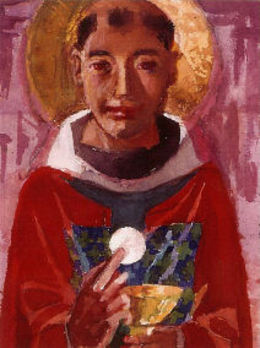

St John Roberts

St John RobertsFriday 16th July 2010

The Archbishop of Canterbury preached at Westminster Cathedral on the occasion an ecumenical celebration of the four-hundredth anniversary of the death of St John Roberts.The service was attended by the Anglican and Roman Catholic bishops of Wales and many pilgrims from the churches in Wales.

The Archbishop of Canterbury addressed the congregation in both English and Welsh. This was the first time the Welsh language was used in an official capacity within the walls of Westminster Cathedral.

The Archbishop said: "It was a real joy, when we gathered in Westminster on 17 July to give thanks for the witness of St John Roberts, that we were able to celebrate the grace and holiness of God in all the saints of Wales - the famous and the not so famous - and to share in the language and the music that has given voice to their prayers and witness over the centuries."

Read a transcript of the Archbishop's sermon in Welsh and English below, or click download on the right to listen [15Mb]

Sermon for 400th anniversary of the death of St John Roberts

Lectionary: Wisdom 3.1—9; John 12.23—26

Mae hi'n ddigon hawdd, rhy hawdd yn wir, meddwl am merthyron Cymru a Lloegr yn ystod teyrnasiadau Elisabeth Tiwdwr ac Iago I fel pleidiwyr gorffenol Catholig – dynion a benywod yn gwrthwynebu cyfnewidiad, gwrthwynebu yn arwrol, mewn modd mor brid a phosib. Fallai credwch fod y cyfnewidiad hon wedi bod yn fradychiad ofnadwy; fallai credwch ei bod hi'n wawr oes newydd, oes gwelliant a chynnydd crefyddol. Beth bynnag, oedd pobl fel John Roberts siwr o fod yn amddiffynwyr teyrngarwch i ddoethineb canrifoedd 'Christendom', yr hen byd a'i hen ffydd.

Ond mae'r gwirionedd yn ddramatig wahanol, a llawer mwy ddiddorol. Wrth gwrs, oedd llawer o'r merthyron yn bobl syml, pobl oedd – yn wir – yn deyrngar i'r etifeddiaeth yr 'hen ffydd'. Ond mae hi'n tamaid bach o syndod sylweddoli pa sawl o'r merthyron Cymru a Lloegr oedd yn flaen mudiadau newydd y cyfnod. Oeddynt yn ddinasyddion Ewrop, gynefin â datblygiadau ysgolheigaidd, datblygiadau athronyddol a diwylliannol; oedd llawer—fel John Roberts ei hunan—yn eiddgar ynglŷn ac addysg werinaidd; oedd llawer ohonynt—fel John Roberts unwaith eto—yn aelodau cymdeithasau gyfreithlon yn Llundain, drigolion byd Shakespeare a John Donne. Nid oeddynt yn byw mewn byd sy wedi hanner marw, ond mewn byd yn symud tua orwelion newydd. Oeddynt plant y Dadeni, y 'Renaissance', a phlant ailenedigaeth dychymyg a chreadigolrwydd y cyfnod anarferol hwnnw.

A hefyd oedd llawer ohonynt yn blant mudiadau newydd mewn bywyd ysbrydol. Aeth John Roberts o Lundain i Paris a wedyn i Sbaen, i fynachdy Sant Martin yn Valladolid – canolbwynt teulu mynachaidd yn erwin ac yn ddwys, mewn cyd-destun lle oedd llawer o bethau newydd yn digwydd ynglŷn â bywyd gweddi. Etifeddiaeth bwysig yma oedd etifeddiaeth pobl fel Ignatius Loyola, Teresa o Avila a Sion o'r Groes; pwyslais mynachdai teulu neu 'cynulleidfa' Valladolid oedd bywyd mewnol, bywyd cynhemlad a hunanwybodaeth. 'Renaissance' gweddi a chynhemlad oedd hon – rhyw fath o gyfochrog i'r Dadeni diwylliannol. Yn yr ill dau, oedd ysbryd dynol yn darganfod dyfnderau newydd, posibilrwyddau newydd. Yn Valladolid, oedd John Roberts yn eu calonogi symud tua'r ddyfnderau hyn. A phan oedd e'n mynd yn ol i Loegr, gallodd siarad, gallodd gweithredu, oddiwrth y dyfnderau – yn ei wasanaeth er y cleifion, yn ystod y pla yn Llundain, yn ei gydymdeimlad tua phawb, tua'r tlodion yn y ddinas. O'r diwedd, gallodd wynebu ei farwolaeth ddirboenus oddiwrth yr un dyfnderau – ar sylfaen distawrwydd a chariad ei brofiad mynachaidd.

Nid yw'r merthyr yn berson sy'n dweud 'Na' i'r byd mewn unrhyw ystyr syml. Mae'r merthyr yn gweld cyfoethogrwydd y byd, cyfoeth bryd a dychymyg, cyfoeth diwylliant a phrydferthwch ysbryd dynol. Ac oherwydd y mae'r merthyr yn gweld y cyfan fel anrheg ac arwydd Duw, mae e'n gwybod bod prydferthwch y Rhoddwr yn ddidderfyn fwy na'r byd i gyd. 'Mwy trysorau sy'n dy enw / Na thrysorau India'i gyd' mewn geiriau ananghofiadwy Williams Pantycelyn ('Iesu, Iesu rwyt ti'n ddigon'). Ac felly y mae'r merthyr yn cychwyn ar y taith i'r 'India' nefol, gwlad rhyfeddodau, yn ei farwolaeth. Mae hi'n gamsyniad ddifrifol a dinistriol meddwl am y merthyr fel rhyw fath o brawf ein cywirdeb, rhyw fath o 'bwynt' mewn ymresymiad. Dathliad yw busnes y merthyr, dathliad y groes a'r atgyfodiad, dathliad creadigaeth newydd. Dim syndod mae hanesydd merthyron yr eglwys hynafol yn aml eu datgan mewn termau sy'n dod o ddiwinyddiaeth ewcarisdtaidd – y merthyr fel ddelw corff sacramentaidd Crist, yr anrheg oruchaf, yr arwydd ddigymar, 'gronyn gwenith' yr efengyl heddiw. Dyma rheswm y gallwn dathlu'r merthyron o eglwysi eraill – gan edifeirwch, gan ddiolchgarwch, Catholigion Rhufeinig yn dathlu merthryon Diwygiedig, a'r Eglwys Anglicanaidd, fel heddiw, yn dathlurheina sy wedi dioddef trwy ei ffyrnigrwydd a rhagfarn. Rwy'n hollol ymwybodol o ddarlun esgob Anglicanaidd Llundain – George Abbott, wedi hynny archesgob Caergaint – yn llywyddu ar dreial John Roberts. Ond heddiw, mae hi'n bosib o'r diwedd dathlu ynghyd – dathlu John Roberts fel arwydd ysblander Duw a felly arwydd nerth a rhyddid Duw sy'n ei ddatguddio mewn cymod cyffredinol.

Felly, pan edrychwn tua dyfodol ein cymdeithas, yng Nghymru neu yn Lloegr, beth yw neges y merthyr? Yr un peth ââ neges yr Eglwys ei hun: os mynnwn weld adnewyddiad cydymdeimlad a gwasanaeth yn ein cymdeithas, mae eisiau arnom gwybod ble mae gwreiddiau prydferthwch ac urddas dynoliaeth i'w ddarganfod. A gwybod lle mae nhw, dyma rhywbeth sy'n tyfu ar ddaear cynhemlad a sy'n dod yn weledig mewn dathliad, hyd yn oed yn wyneb perygl a dychryn a marwolaeth. Mae tystiolaeth y merthyr yn dweud rhywbeth inni ynglŷn ac urddas dynol – ond, pwysicach na hyn, rhywbeth ynglŷn a'r ffaith bod dynion a benywod wedi'u creu er mwyn llawenydd. Mae llawenydd sy'n dod o bywyd diwylliannol a chreadigol, llawenydd a balchder am etifeddiaeth cenedl, yn ein atgoffa o'n gwreiddiau, nid yn unig mewn bywyd y genedl, ond mewn anrheg Duw. Oedd John Roberts yn eitha gynefin a phleserau'r bryd a dychymyg, gogoniant a chymhlethdod dyn; ond aeth ymlaen, aeth yn fwyfwy tu mewn i'r ddyfnderau, i'r ddaear lle bydd y gronyn yn marw mewn tywyllwch. Ond yna daeth o hyd i ffynhonnau adnewyddiad, sy'n dyfrhau eglyws, cymdeithas, bydysawd i gyd – creadigaeth newydd, lle 'ni bydd marwolaeth mwyach', ni bydd anghyfiawnder a thrais mwyach . Fel pob Merthyr, ac yn wir fel pob Cristion, meddai John Roberts, gyda'i gyfoeswr John Donne, 'Marwolaeth, byddit ti'n marw.'

It's easy, indeed it's far too easy, to see the Welsh and English martyrs of Elizabeth I's and James I's reigns as champions of a Catholic past – men and women who heroically resisted change in the most costly way possible. You may believe that this change was a terrible betrayal of a universal Christian history; or you may think that it was the dawn of a new age of religious progress. But whichever way you come at it, surely figures like John Roberts were standing for loyalty to the inherited wisdom of the centuries of 'Christendom', the old world and its old faith.

The truth is dramatically different and far more interesting. Of course many of the martyrs were unsophisticated people who were indeed simply loyal to the heritage of the 'old religion'. But it's a bit of a surprise to realise just how many of the English and Welsh martyrs were in the forefront of the new movements of the age. They were citizens of Europe, familiar with the developments in scholarship that were going forward, with movements in philosophy and culture. Many—like John Roberts himself—were enthusiasts for popular education. Many—again like John Roberts—were members of the Inns of Court, inhabitants of the world of Shakespeare and John Donne. They didn't live in a world that was half-dead but in a world moving towards new horizons. They were children of the Renaissance, children of the rebirth of imagination and creativity in that extraordinary period.

Many of these people were also the children of the new movements in spirituality. John Roberts went from London to Paris and then to Spain, and first to the monastery of Saint Martin in Valladolid – the centre of a severe and serious monastic family, in a context where many new things were going on in the life of prayer. The heritage that mattered here was the heritage of people like Ignatius Loyola, Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross; the emphasis of this monastic family, the Congregation of Valladolid, was on the inner life, the life of contemplation and self-knowledge. This was a 'renaissance' of prayer and contemplation, a kind of parallel to the cultural renaissance. In both, the human spirit was able to discover new depths and new possibilities. In Valladolid, John Roberts was encouraged towards these depths. And when he returned to England, he was able to speak and act out of these depths – in his ministry to the sick at the time of the plague in London, his compassion for all, his service to the poor of the city. And at the end, he was able also to face the appalling agony of his death out of those same depths, on the foundation of the silence and love of his monastic experience.

The martyr isn't a person who says 'No' to the world in any simple sense. The martyr sees the richness of the world, the wealth of mind and imagination, the wealth of culture and the beauty of the human spirit. And because he sees the whole as the gift and sign of God, he knows that the beauty of the Giver is infinitely more than the whole world itself. 'More treasures are found in your name than in the whole of India', in the unforgettable words of Williams Pantycelyn in the greatest Welsh hymn of the eighteenth century ('Iesu, Iesu rwyt ti'n ddigon' – 'Jesus, Jesus all-sufficient'). And so the martyr sets out on the journey to a heavenly 'India', a land of marvels, through his death.

It is a serious and destructive mistake to think of the martyr as some sort of proof of how right we are, some sort of 'point' in an argument. The martyr's business is celebration, celebration of the cross and resurrection, of the new creation. It's no surprise that the records of the martyrs of the early Church are so often couched in terms of eucharistic theology – the martyr as an image of the sacramental Body of Christ, the supreme gift, the sign without parallel, the 'grain of wheat' of today's Gospel. Which is also why we are able to celebrate the martyrs of churches other than our own – with penitence and with gratitude, Roman Catholics celebrating the Reformed martyrs, the Anglican Church celebrating, as we do today, those who were victims of its own violence and prejudice. I'm very conscious of course of the picture of the Anglican bishop of London—George Abbot, later Archbishop of Canterbury—presiding at the trial of John Roberts. But today it is possible at last to celebrate together – to celebrate John Roberts as a sign of the splendour of God and so of that divine power and liberty that is revealed in universal reconciliation.

So, when we look towards the future of our society, in England or in Wales, what is the martyr's message? The same as the message of the Church itself: if we want to see a renewal of compassion and service in our society, we need to know where the roots of human beauty and dignity are to be found. And to know where these roots are is something that grows on the soil of contemplation and becomes visible in celebration, even in the face of danger, terror and death. The martyr's witness tells us something about human dignity – but, more importantly, something about the fact that men and women are created for the sake of joy. The joy that comes from the life of culture and creativity, the joy and pride we feel in the heritage of a nation, reminds us of our roots not only in the life of the nation but in the gift of God. John Roberts was familiar enough with the pleasures of the mind and imagination, the glory and complexity of humanity; but he travelled further still, more and more deeply into the depths where the seed dies in darkness. (John 12.24) But there he found the wellsprings of renewal that water the Church, the society we live in, the whole world, the whole universe – the new creation where 'death shall be no more' where injustice and violence shall be no more. Like every martyr—indeed, like every Christian—John Roberts proclaims, with his contemporary John Donne, 'Death, thou shalt die.'

Welsh and English originals © Rowan Williams 2010