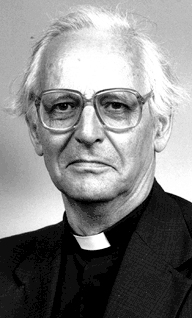

Archbishop pays tribute to Henry Chadwick

Tuesday 24th June 2008

Dr Rowan Williams pays tribute to the life of theologian Henry Chadwick in an obituary published in the Guardian newspaper. 'The Anglican church," it was said, "may not have a Pope, but it does have Henry Chadwick." Nothing could better illustrate the unique position held for many years by this aristocrat among Anglican scholars, who has died aged 87. His erudition was legendary, in practically all areas of the study of late antiquity, but it was also deployed to memorable effect in the work of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission.

'The Anglican church," it was said, "may not have a Pope, but it does have Henry Chadwick." Nothing could better illustrate the unique position held for many years by this aristocrat among Anglican scholars, who has died aged 87. His erudition was legendary, in practically all areas of the study of late antiquity, but it was also deployed to memorable effect in the work of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission.

Many sensed that the more recent history of Anglican-Roman Catholic relations was a source of some sadness to him. He had little love either for radical fashions in theology or for the fierce neoconservatism characteristic of some parts of the Roman Catholic church in recent decades. He represented that earlier and more hopeful phase, begun and aborted in the 1920s at the Malines conversations (named after the French spelling of the Belgian city of Mechelen where they were held), where Anglicans and Roman Catholics discovered unexpected common ground in the study of the fathers of the church and in a deep but unobtrusive liturgical piety.

In that first spring of ecumenicalism exchange, continental Catholic scholars came to regard Armitage Robinson, dean of Wells, as the summation of everything admirable in Anglican devotion and learning. In that respect, Henry was undoubtedly Robinson's heir. It often seemed that, at any major ecumenical gathering, some representative of a foreign communion would sudddenly wax eloquent about what Henry was and represented. And, as a devout savant of the kind he was, he might be said at times to have reminded Anglicanism of its better self.

He once proclaimed ecumenism "a good cause to die for", and was certainly deeply committed to finding consensus - not by coining a conveniently vague formula, but by a real excavation of common first principles. On matters where this seemed utterly elusive - such as the debates over women's ordination - he felt, I think, impotent and frustrated. He had no relish at all for conflict, even for the gentlemanly blood sport of academic controversy. His learned work is notably short on open war with other scholars, even where it is advancing new and potentially controversial conclusions. The fastidiousness made some of his professional life very hard.

Henry was born in Bromley, Kent, into an accomplished, academic family. His father, John, was a leading barrister; his elder brother, Owen, became an authority on ecclesiastical history. Educated as a king's scholar at Eton, Henry became a music scholar at Magdalene College, Cambridge - he retained a lifelong passion for music in general and church music in particular - while also studying divinity at Ridley Hall.

He graduated in 1941 and became a fellow of Queens' College, Cambridge, in 1946 following a short spell as assistant master at Wellington school, Somerset. At a relatively young age he moved from Cambridge to take up the regius chair of divinity at Oxford in 1959, which he occupied with distinction for 10 years.

Henry had already established himself in the field with a superb translation of an early work of Christian apologetic, Origen's Contra Celsum (1953), and had assumed the editorship of the Journal of Theological Studies (1954-85). More books, and a steady stream of papers, followed his move to Oxford, including works on Sextus and St Hippolytus.

In 1969, however, he paid the price of having won the trust and affection of his college when he was appointed dean of Christ Church. The scholarship never dried up, and Henry became a venerated figure on a wider stage, presiding with inimitable grace and dignity in his cathedral. But the college went through some contentious and bad-tempered times, and he was much worn down by the storms of donnish ego that swirl around every Oxbridge institution. He suffered, too, from the last relics of old-style anti-clericalism in Christ Church. Altogether these cannot be said to have been happy years, though in 1976 he produced a widely admired study of the little-known early Christian figure and heretic, Priscillian of Avila.

His move back to Cambridge in 1979, to the other regius chair of divinity, which he occupied until 1983, was clearly a relief. In Cambridge his lectures were as popular as ever with a new generation of undergraduates, and still more substantial research saw the light of day. When in 1987 he was persuaded out of retirement to become master of Peterhouse, Cambridge, the experience did something to redeem the memories of running a college. He was more manifestly at home than he had been in the deanship, and was universally seen to have steered this college into calm waters by the time he left the post in 1993.

Henry was a profoundly shy and private man for all the generous hospitality that he and his wife Margaret "Peggy" Browning, a constant, "lively, intelligent and warm-hearted support" whom he married in 1945, offered in all their various homes. The dislike of confrontation could lead not only to the almost incredibly judicious and Olympian style of conversation (beautifully and affectionately caught by JIM Stewart in his "Surrey" novels about Christ Church, where the provost is clearly drawn from Chadwickian life), but at times to a real unwillingness to express commitments - on matters of learned detail, on issues in contemporary theology, on public affairs - and some found this tantalising, to say the least. Yet its positive fruit was shown in the results of the Anglican-Roman Catholic conversations, where his hugely resourceful reticence somehow drew out possibilities of reconciliation.

Many (sometimes surprising) names from all over the globe will bear witness to his unfailing kindness to, and encouragement of, younger scholars. The innate shyness behind the massive and majestic public and academic presence meant that there was never a "school" of Chadwick disciples. But, if anything, this meant that his mark was more widely imprinted.

No one could replace Henry and no one will. The Anglican church no longer shows so clearly the same combination of rootedness in the early Christian tradition and unfussy, prayerful pragmatism, and the ecumenical scene is pretty wintry with less room for the distinctive genius of another Chadwick. But the work done stays done, and it is there to utilise in more hospitable times.

But, meanwhile, there can be no doubt that Henry will be remembered as one of the most influential and admired Anglicans of the century, in church and academy alike.

He is survived by Peggy and their three daughters, Priscilla, Hilary and Juliet.

· Henry Chadwick, theologian, born June 23 1920; died June 17 2008.