Archbishop highlights importance of local churches in communities

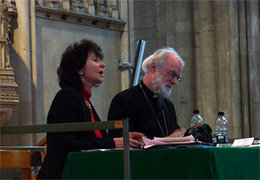

The Archbishop with fellow poet Ruth Padel

The Archbishop with fellow poet Ruth PadelFriday 30th April 2010

The Archbishop of Canterbury spent two days in the Diocese of Norwich, reflecting on the life of the rural church at All Saints', Sharrington, and taking part in a conversation on the relationship between poetry and prayer in Norwich Cathedral. The Archbishop frequently visits other dioceses as part of his ministry.On Friday 30 April, the Archbishop gave the Sharrington lecture in a small rural church. He challenged people: "I think a lot of people take the church a bit for granted. They'd miss it if it wasn't there....If people really want to see that unique presence there in the next generation, they will have to be a bit more proactive about it."

Read a transcript below, or click link on the right to listen to the lecture [30Mb]

In Norwich Cathedral the following day the Archbishop took part in a conversation about the relationship between poetry and prayer with fellow poet Ruth Padel (pictured above), great-great granddaughter of Charles Darwin. During the discussion they each read a selection of their own and others' poetry.

Click link on the right to listen to the conversation and poetry [35Mb]

A transcript of the Archbishop's Sharrington Lecture follows:

To have the opportunity of thinking out loud with you for a bit about the Rural Church and the rural experience has been for me a real stimulus and opportunity to put ideas together which I hope are relevant not just to thinking about rural society but perhaps a little bit to our society as a whole.

One of the things that an Archbishop of Canterbury cannot avoid being involved in is the process of nominating Bishops to the Prime Minister and the Crown. And quite often in the Crown Nominations Commission, somebody will say about this diocese or that, ‘well, we’re looking for somebody who has rural experience’; and we then go into a very long and sometimes slightly bad-tempered discussion about what ‘rural experience’ is, because in this country the reality of non-urban life is astonishingly varied. In the UK, ‘rural’ can mean the hill farms that my fellow countryman R S Thomas writes about in his poems. It can mean the Cotswolds, and the picture book and chocolate-box countryside that’s so popular in parts of the national imagination. It can mean commuters in Ashford, it can mean agri-business in East Anglia, it can mean the seasonal poverty of a tourist-dominated economy in Cornwall or the Lake District, and – even in one county like this – it can mean a wide variety of realities which you know better than I do.

Is there anything that all these varieties of non-urban life have in common? Sadly, the first thing that they seem to have in common when we begin to reflect on this, is a series of absences: things that aren’t there. Public transport for example, or concentrated retail outlets – and that means of course that rural life (in contrast to the fantasies of some people), is not ever these days simply a matter of sitting in one place for ever. Rural life is remarkably mobile. It involves budgeting for travel in all kinds of ways, travel to shop, travel for medical services and very often of course, for farming communities, the routine travel involved in that. And that’s before we even begin to think about the lives of commuters in some bits of supposedly ‘rural’ England.

It’s quite important to remember this, because the language about the countryside as ‘timeless’ and ‘static’ is still very deeply ingrained in some people’s minds. While I think I see what that means, whenever I’ve been in rural environments the words ‘timeless’ and ‘static’ have actually not been the words uppermost in my mind. Some of you will remember a speech by John Major about the essence of English identity, which had to do with warm beer and the sound of bats and balls on a summer evening and spinsters cycling to Holy Communion through the early morning mists. It was a catalogue which he derived from an essay by George Orwell some fifty years earlier, and it does of course sum up the mythology that surrounds rural experience in lots of people’s minds. But in fact, even fifty years before John Major, it was a rather slanted and partial picture of the countryside. It took for granted that image of something unchanging, something which in a way took us right out of the stresses, changes and choices of modern life.

And the first point I want to make tentatively (because you know more about rural experience than I do) is that I really don’t think that it’s helpful to see the countryside as timeless in that way. The countryside, as we’re often reminded, is partly a human creation. Generations and generations of labour, of real involvement, wrestling with the environment, have made the countryside what it is. We are not stone-age peasants huddling in huts surrounded by untamed nature. Rural life is life which reflects a long history of -- could we dare to say? – humanising the environment around us. And that of course is one of the things that is sometimes forgotten when people speak about rural experience – especially about farming life; the aspect of what I can only call the custodianship of the faming community in the countryside. They have transformed a landscape, made it their own and that is part of the legacy we all share. Ignore that aspect of rural life and especially farming life, and you ignore something really central and really significant in the life of the wider national community.

But I suppose what is true, in a way, about that rather romanticized picture of the countryside is that there is always in rural experience the element of having to wrestle with what’s there, to deal with and engage with what is given. You don’t choose the soil, you don’t choose the landscape and above all you don’t choose the weather. But the countryside is the result of generations of engagement, creative involvement with a landscape – which means quite simply that human skill, human labour and human imagination have been caught up in trying to make something out of an environment which pushes back, which resists, which is difficult, stimulating and sometimes intensely frustrating, whether it’s landscape, soil or weather that we’re speaking of. It means that the human experience in the rural environment is never going to be one in which the human will, human choices, are completely in charge, and it’s never going to be one in which one place is exchangeable with another. The particularities of landscape and soil and weather mean that what rural life is like in Norfolk is not what rural life is like in Carmarthenshire. Back to where I started: rural is a hugely varied term because landscape and soil and weather are different and ‘rural experience’ means you can’t avoid the sense of particularity; being here rather than somewhere else. One of the great sadnesses of an age of mass-communication – I don’t think it’s reversible – is that we all increasingly are drifting towards speaking the same kind of English; the erosion of dialect as part of the distinctive local identity does seem to me rather sad.

Life in the country is never going to be life that is nowhere in particular. And one of the problems that the modern urban experience faces is a question of what it does to the human mind and imagination to live ‘nowhere in particular’. I used to know an eccentric Canadian sculptor who argued that airports were a systematic attempt by those in authority to prepare us for living in outer space – because, he said, an airport is the supreme example of being nowhere in particular, and because there’s no ‘landscape’ in outer space – as far as we can see – that’s how we get ready for it.

But rural experience involves that dialogue between what’s there, what’s given, and the needs and skills of human communities and human individuals; a dialogue, which, like every dialogue, produces something utterly distinctive and utterly different in every context. What’s given is different, and the needs and the skills are different as well. The landscape matters and the weather and the soil matter. So is it right to say that rural experience is about human interdependence? Recognising that the human world is not just one that we’ve made up, but one that we’ve worked out in dialogue? Human experience is not just human beings deciding that ‘this is what we’re going to be, this is how we’re going to exist’, and driving on with that agenda. No, it is about pushing and being pushed at, giving and receiving, feeling, molding, sensing and proposing a dialogue. And there’s something about the essence of being human contained in that which certain kinds of modern urban experience encourage us simply to forget. Rural experience deflates some of our more extravagant expectations around human power and human control. The weather and the soil mark the inescapable physical dimension of being human. You can’t suppose that you’re just a mind or a will or a fancy floating in mid-air. Urban experience seems to be so consistently put before us as the norm for all real serious human experience, and this can corrupt our sense of what is genuinely human.

I’m talking of course about the experience of prosperous urban life - because of course the experience of the urban poor is an experience of even greater helplessness and powerlessness than that of those in a rural environment; they, at least as much as anyone in the countryside, have to negotiate their own freedom in relation to what is often a very brutally and inhumanly given environment. But I’m speaking about the way in which a highly metropolitan media, a very metropolitan and cosmopolitan sense of what is an appropriate and achievable lifestyle, constantly reinforce in us the feeling that real ‘grown up’ contemporary humanity is about choice and control. And because in rural life choice and control are never going to be everything, rural life has something to say that is really rather important for our humanity’s good.

I was speaking the other day to someone who was expressing an increasing concern about the way in which electronic communication pushed us further and further away from face to face relation, to the extent that in some electronic contexts people seemed genuinely to believe that their real identity is what they construct through that medium rather than their own embodied reality, vulnerable and local. We do, I think, have some real cultural questions there, which we’re not thinking seriously enough about at the moment.

So far I’ve spoken in rather general terms about rural experience and I haven’t spoken very much about Christianity and the rural church. I want now to move on to reflecting a bit on what Christianity has to say about the rural and urban reality of human life. One of the great slogans sometimes used about the Bible is that it is a story that begins in a garden and ends in a city. I think that’s a very important half-truth. The garden where things begin is of course a garden in which the experience I’ve just been talking about hasn’t yet begun – the experience of real creative engagement and struggle. And the city where the story ends is remarkably unlike some of the modern metropolises that that we think about; it has, for example, a very considerable river running down the middle of it with trees by the side. It also has at its centre a mystery: in the Revelation of John the City of God is centered on the new temple, which is the person of the Lamb of God. So far from this city being a place where every individual’s choice and control is privileged, everything in this city flows to and from the mystery which makes us human; the sacrificed lamb, the saviour, the one with whom we all have to find our way to be human; because if we try to go by any other route we shall end up being less than human; the Way, the Truth and the Life.

This is a city in sharp contrast to the typical modern city because at its heart is what we can never manage and never control: the mystery of God’s love. In dialogue with that mystery we become human. It’s as if the city that comes at the end of the Bible story is a city which has embraced what is most significant in the rural experience. Becoming human in dialogue with what is mysterious, strange, uncontrollable, sometimes beautiful and often terrifying, this element of the rural experience is carried over into the vision of the city of God, so that we cannot say that the city of God is a city like the average metropolis of late modernity – a place on the one hand dominated by technological wizardry and control, and on the other hand living with an immense surplus human population of powerless and forgotten people. God’s city is a city where every eye is drawn towards the mystery which creates community. Something of what is learned of the rural experience in other words is there at the heart of that ultimate, creative, redeemed community which stands at the end of the Bible story; and the worst fate for any city would be to be sealed off in its own fantasies about technology and control, wealth and security.

So in our contemporary society, I’m suggesting, the rural experience has something profoundly challenging, disturbing and necessary to say to the whole of our experience of our culture. And the rural church – to come at last to that central topic for tonight’s reflections – is among other things, a sign of the rural community being aware of itself. The rural church is there to remind people what the human experience is like, in this place, in this time. And that works in at least three ways. The rural church speaks of the past, it speaks of the cumulative heritage of art and imagery and skill. It speaks of people’s engagement with both nature and the materials that it uses – the wonderful presence in so many churches across our country of local material built into and sanctified by a church building. It speaks too of an engagement with faith, it speaks of the images of an integrated, more healed, life that emerges from that engagement with the mystery of the world around. It speaks of the past; all of that legacy of skill and imagination, born of the experience of local wrestling and engagement with the mysteriousness and the uncontrollability of the environment is held, physically, in this building.

Second – as you’ll be reminded if you look out of the window – it speaks of death. It speaks of the fact that human beings come and go in this place. It speaks of limits, frailty, ends, the passage of time. It tells us that death is both tragic and normal, that there is no way of living humanly that doesn’t at some point and at some level have to come to terms with the fact that we die and that that is all right. Death is here, recognized, visible – faced not simply feared, made something of, faced and understood a bit, but part of a human, imaginative landscape.

And the rural church speaks, thirdly, of solidarity, of belonging, the fact that the community of any one place is not just the people who happen to be there at any one moment. Somehow, who we are and what we are is bound up with far more than we can see, understand or even imagine. History, death, belonging: great, sombre, significant facts about humanity; and here they are, encoded in this building and what lies around it. A reminder, at the very least, of humanity: creative, mortal, involved with each other, triumphing in imagination, defeated in death, present still. That in itself is quite an agenda for the local church to carry both as a building and as a community – the calling to represent in this locality but also more widely in society those great facts about our humanity. We have a past, we face a death, we belong with one another. That in itself is the beginning of a Gospel. But that alone perhaps doesn’t amount to very much more than the sort of thing that Philip Larkin wrote about in his famous poem on churchgoing: the sense of seriousness, being in ‘a serious place on serious ground’ with the dead lying around. It’s not quite enough as an account of what the rural church is about. There may be – one can imagine it – or could have been, other signs of history and death and belonging. But the rural church is more than that, it’s at least all that (and that’s a lot), but it’s more. This building, the focus of these reflections on time and death and solidarity, this building is also a building that houses something. It houses a table where God, made human, eats with us. It houses a sign of a God who is so hospitable, so welcoming to what he has made that he meets us at our level and speaks to us in our language. This building houses a story, a human story which is also God’s, the story of how God the infinite beyond all place and time has made his own place and time and words, how God has made himself accessible and makes himself accessible day after day. In the memory, the re-enactment, of the story of his time with us in Jesus of Nazareth, that table and that cross tell us what we need to know about the reality that frames all of our thoughts, about history and death and solidarity. It tells us that the history of human beings is in the hand of love, that the death of human beings opens out onto resurrection and that the solidarity and belonging-together of human beings is finally a belonging with God himself. So those three themes may be great and wonderful in themselves, but, housed here in the presence of the table and the cross, they are immeasurably greater and immeasurably more promising. They tell us that the final truth about human beings is indeed not a ‘nowhere-in-particular’, but a real rootedness in a world whose reality has been embraced by God in all its physical and particular truth.

In conclusion then: I’ve been suggesting that at level one, rural experience generally has an essential word for urban experience and for our culture more widely. It is an obstinate and perhaps rather annoying reminder that we’re not ultimately in charge of things like soil and weather, we’re discovering our humanity in dialogue with the world around us, not just imposing an agenda. At level two, all of that comes to be much more visible, much more clearly expressed, in this building which embodies a history, which embodies the facts of the passage of time and the reality of death, and which also opens our imagination out onto the mysterious distant depths of the community we belong to without realizing it. But at level three, this is a building that not only embodies all those facts about human experience as it’s lived out very particularly in the rural setting, it houses the memorials of the story of God’s love holding us where we are as we are, body and spirit, local and universal, limited and creative, all of that together. If rural experience has an essential word for urban experience, the rural Christian experience, the experience of the historic church has still more to say, a word to say on behalf of a particular kind of humanity which I hope is the kind of humanity we really want to see spread around the place these days: a humanity conscious of being created and mortal, and conscious also of being loved and stretched and changed – as opposed to the fictional humanity which sadly so much of our culture seems to be in love with; the humanity that’s in charge, the humanity that seeks greater and greater control, greater and greater independence and greater and greater freedom to live nowhere in particular.

To that, this place, and what it stands for speak a word on behalf of what we can only call wisdom. Wisdom, remember, in the Old Testament isn’t just abstract good advice, wisdom is God’s gift in the world, of clues, pathways, which connect us to one another and to God’s own creative imagination and transfiguring love. ‘Wisdom has built herself a house’ is one of the great images in the book of Proverbs; and perhaps, when we come into a church like this, that phrase could be in our minds: ‘this is a house wisdom has built’. And those who frequent this house are called on to be wise in their generation, as against the folly of an abstract, deluded, saddened and diminished humanity.