'Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread' - Archbishop's address at Lutheran World Federation Assembly

Thursday 22nd July 2010

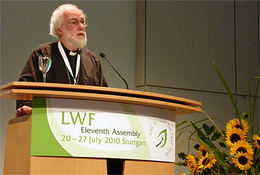

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, has delivered the keynote address on the theme' Give us this day our daily bread' at the 11th Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation in Stuttgart, Germany.The Assembly is the Lutheran World Federation's highest decision-making body, which this year runs from 20-27th July, normally occurring every six years.

The Archbishop's keynote address reflected the Assembly's theme of 'Give Us Today Our Daily Bread', in which he explored a number of interpretations of this line from the Lord's Prayer: "The bread that is shared among Christians is not only material resource, but the recognition of dignity...and to recognise human dignity in one another is indeed to share the truth of what humanity is in the eyes of God. We feed each other by honouring the truth of the divine image in each other."

Dr Williams also used his address to outline the close connections that can be observed between this prayer for daily bread and that of forgiveness, describing forgiveness as ""a radical way in which to nourish one another's humanity" and that "Forgiveness is the exchange of the bread of life and the bread of truth; it is the way in which those who have damaged each other's humanity and denied its dignity are brought back into a relation where each feeds the other and nurtures their dignity".

The Archbishop concluded his address by saying:

" 'Give us this day our daily bread' is thus a prayer for the fullness of the Church to be made manifest: in a pattern of recognising our own need and the neighbour's, and being able to turn with confidence to each other so that the need may be met; in the desire for the freedom to forgive and be forgiven; in the fuller understanding of the Eucharist as the centre of our Christian identity – not purely as a ritual act but as a foundation for community, a sharing of bread embedded in a practice of shared life, flowing out into the service of the world's hunger. It is a prayer, simply, for Christ to be our food and sustenance, so that all self-sufficient pride, all individual anxiety and defensiveness, all greedy effort to live at the expense of the neighbour are overcome; and the Church declares with clarity and conviction that there is indeed bread for the world's hunger to be found in the Body of the Lord. May that clarity and conviction – and the repentant self-awareness that goes with it – be always ours."

Read a transcript of the Archbishop's address below, or click download to listen [29Mb]

Keynote Address by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams

1.

Jesus speaks in the gospel (Mt7.9) of how the human parent will not give a child a stone when the child asks for bread. If we ask for bread, one thing that will persuade us that the response is satisfactory is the knowledge that our own declaration of what we need has been heard. Part of the nourishment we need is knowing that our sisters and brothers in faith see and hear our needs as they are, not as others imagine them to be. The bread that is shared among Christians is not only material resource but the recognition of dignity. One of our great Welsh Christian poets, R.S.Thomas, published a collection of poems in 1963 called The Bread of Truth; and to recognise human dignity in one another is indeed to share the truth of what humanity is in the eyes of God. We feed each other by honouring the truth of the divine image in each other.

'Give us this day our daily bread' thus becomes a prayer that asks God to sustain in us the sense of our humanity in its fullness and its richness; to give us those relations with other human beings that will keep us human, aware of our mortality and our need, yet confident that we are loved. It is a prayer to be reminded of our need: let us never forget, we pray, that we have to be fed, and that we cannot generate for ourselves all we need to live and flourish. And at the same time, it is a prayer that we shall not be ashamed of our mortality, our physical and vulnerable being. We start from need – where else can we start? But that is a way into understanding how and why we matter, why we are valuable. The prayer poses a critical question to anyone who imagines that they can begin from a position of self-sufficiency; it affirms that to be in need of this 'bread of truth', in need of material or spiritual nurture, is in no way a failure but, on the contrary, a place of dignity. The prayer both challenges the arrogance of those who think they are not in need and establishes that the needy are fully possessed of a treasure that needs to be uncovered and released, the humanity that draws them into mutual relation.

2.

Part of what we are praying for in these words is the grace to receive our own humanity as a gift. We ask for openness and gratefulness to whoever and whatever awakens us to our dignity and helps us realise that, while our dignity is essentially and primarily given in our creation, it is always in need of being called into active life by relation, by the gift of others. And the implication is clear that we should in doing this pray to be kept awake to what we owe to the neighbour in terms of gift; their humanity depends on ours as ours does on theirs. Many commentators on the Lord's Prayer, such as Gregory of Nyssa, underline the irrationality of praying for our daily bread while then seeking to hold on to it at the expense of others in one way or another. And in the framework I have been outlining, this can be by way of a concern for defending my own dignity rather than being willing to receive it in love.

Praying for our daily bread is praying to be reacquainted with our vulnerability, to learn how to approach each other, not only to approach God, with our hands open. So to pray this prayer with integrity, we need to be thinking about the various ways in which we defend ourselves. We cannot fully and freely pray for our daily bread when we are wedded inseparably to our own rightness or righteousness, any more than we can when we are wedded to our own security or prosperity. And perhaps this explains why the Lord's Prayer at once goes on to pray for forgiveness, or rather for the gift of being forgiven as we have learned to forgive. The person who asks forgiveness is a person who has renounced the privilege of being right or safe; he has acknowledged that he is hungry for healing, for the bread of acceptance and restoration to relationship. But equally the person who forgives has renounced the safety of being locked into the position of the offended victim; he has decided to take the risk of creating afresh a relationship known to be dangerous, known to be capable of causing hurt. Both the giver and the receiver of forgiveness have moved out of the safety zone; they have begun to ask how to receive their humanity as a gift.

Forgiveness is one of the most radical ways in which we are able to nourish one another's humanity. When offence is given and hurt is done, the customary human response is withdrawal, the reinforcing of the walls of the private self, with all that this implies about asserting one's own humanity as a possession rather than receiving it as gift. The unforgiven and the unforgiving cannot see the other as someone who is part of God's work of bestowing humanity on them. To forgive and to be forgiven is to allow yourself to be humanised by those whom you may least want to receive as signs of God's gift; but this process is intrinsically connected with the prayer for daily bread. To deny the possibilities of forgiveness would be to say that there are those I have no need of because they have offended me or because they have refused to extend a hand to me.

To forgive is clearly the mark of a humanity touched by God – free from anxiety about identity and safety, free to reach out into what is other, as God does in Jesus Christ. But it may be that willingness to be forgiven is no less the mark of a humanity touched by God. It is a matter of being prepared to acknowledge that I cannot grow or flourish without restored relationship, even when this means admitting the ways I have tried to avoid it. When I am forgiven by the one I have injured, I both accept that I have damaged a relationship, and accept that change is possible. And if the logic of the Lord's Prayer is correct, that acceptance arises from and is strengthened by our own freedom to bring about the change that forgiveness entails.

Forgiveness is the exchange of the bread of life and the bread of truth; it is the way in which those who have damaged each other's humanity and denied its dignity are brought back into a relation where each feeds the other and nurtures their dignity. It is a gross distortion of forgiveness that sees it as a sort of claim to power over the other – being a patron or a benefactor towards someone less secure. We should rather think of those extraordinary words in the prophecy of Hosea (11.8-90) about the mercy of God: 'How can I give you up, O Ephraim? For I am God and not a mortal'. To forgive is to share in the helplessness of God, who cannot turn from God's own nature: not to forgive would be for God a wound in the divine life itself. Not power but the powerlessness of the God whose nature is love is what is shown in the act of forgiving. The believer rooted in Christ shares that powerlessness, and the deeper the roots go the less possible it is not to forgive. And to be forgiven is another kind of powerlessness – recognising that I cannot live without the word of mercy, that I cannot complete the task of being myself without the healing of what I have wounded. Neither the forgiver nor the forgiven acquires the power that simply cuts off the past and leaves us alone to face the future: both have discovered that their past, with all its shadows and injuries, is now what makes it imperative to be reconciled so that they may live more fully from and with each other.

3.

This assembly is today focusing on the gifts and needs of Asia – which means, ironically, that the imagery of bread is less apt and immediate than that of rice. That in itself reminds us that so often we try to give to the other what they do not want or need, what is not familiar or nourishing. Sharing the bread of truth means also attending to the truth of the other's actual condition. And much of what we European Christians ask forgiveness for is always going to be those moments in our history when we have offered a gift in a way that cannot be received – perhaps because it is bound to alien cultural assumptions, or more seriously because it is associated with practices of oppression and exploitation. In the Body of Christ, sooner or later, we cannot avoid the moment when we make our peace by recognising that we need each other; that we must learn to open our hands for the rice that our Asian neighbour offers.

In contrast to what the secular culture sometime seems to think, this turning to one another in recognition of mistakes and hurts is not a futile indulgence in meaningless collective guilt or an attempt to settle scores. It is rather that we come to see how our history together has often made us less and not more human, and acknowledge that the effects of that are still powerful in our lives now. So we begin to ask one another for nourishment, including the not always easy or welcome nourishment that comes from hearing the truth.

One other crucial focus today is, of course, the act of reconciliation with Christians of the Mennonite/Anabaptist tradition. It is in relation to this tradition that all the 'historic' confessional churches have perhaps most to repent, given the commitment of the Mennonite communities to non-violence. For these churches to receive the penitence of our communities is a particularly grace-filled acknowledgement that they still believe in the Body of Christ that they have need of us; and we have good reason to see how much need we have of them, as we look at a world in which centuries of Christian collusion with violence has left so much unchallenged in the practices of power. Neither family of believers will be simply capitulating to the other; no-one is saying we should forget our history or abandon our confession. But in the global Christian community in which we are called to feed one another, to make one another human by the exchange of Christ's good news, we can still be grateful for each other's difference and pray to be fed by it.

4.

Scholars at least since the time of St Jerome have worried over the odd Greek word that is used in the gospels for 'daily bread' – epiousios, whose exact meaning has proved elusive. Jerome rendered it with grim literalism as 'supersubstantial' – not a very helpful translation, and not one that has survived in liturgical Latin, but it has prompted a good many fanciful speculations. It probably means simply 'the food on which we subsist'. But Jerome himself refers to an ancient Aramaic version which presented the prayer as 'Give us today the bread of tomorrow.' If that represents what Jesus said, then he was telling us to pray for the gifts of the coming Kingdom to be received in the present. And if so, all that has been said so far is cast in a new light. The need, the hunger, we must learn to express is a need not simply for sustenance but for God's future. What we need is the new creation, the bread that comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.

This suggests a still closer connection between the prayer for daily bread and that for forgiveness. Mutual reconciliation is one of the marks of the work of the Spirit, a radically new possibility opened up through the Body of Christ: it is itself a sign of God's future at work, and so an instance of 'tomorrow's bread'. To put it more fully, the unveiling of our mutual need and the shared recognition of human dignity as something realised in communion are dimensions of our human experience in which God's future is visible. And where these things happen, whether or not they are named in the context of Christ and his Spirit, there is something of the sacramental reality of 'tomorrow's bread' – 'five minutes of heaven', to borrow the title of an English television drama (based on real events) which explored the cost of reconciliation in the setting of Northern Ireland. If forgiveness is the most demanding instance of learning to offer one's own resources for the sake of the dignity of another, if it is in so many ways the least 'natural' or most counter-cultural form of service to each other, it is surely right to see it as a gift from the future, as God's undefeated purpose for us draws us forward.

'Give us this day our daily bread' is, then, a prayer that inevitably looks beyond the present moment and the settling of immediate needs – though at the same time it forbids being anxious about tomorrow. It is as if in order to live in peace and hope today, we have to ask for that foretaste or 'advance payment' of God's future which Paul identifies as the Holy Spirit (II Cor.5.5, cf. Eph.1.14). It has been said that every petition in the Lord's Prayer is implicitly a prayer for the coming of the Spirit (several of the early Fathers noted the ancient variant of 'Thy Kingdom come' as 'May thy Holy Spirit come'), and this is no exception. Praying for the Spirit is indeed praying for the grace to receive our humanity from God at each other's hands in the reality of communion – with all the struggle that this involves in turning towards the reality of the other, not remaining content with our images of each other. Becoming bread for each other means breaking the stony idols of ourselves and the other.

5.

But to speak in these terms of bread and forgiveness and the future presses us towards thinking more about the act in which Christians most clearly set forth these realities as the governing marks of Christian existence: the Lord's Supper, the Eucharist. We celebrate this Supper until Christ comes, invoking the Spirit of the coming age to transform the matter of this world into the sheer gift of Christ to us and so invoking the promise of a whole world renewed, perceived and received as gift. This is, supremely, tomorrow's bread.

But it is so, of course, not as an object fallen from heaven, but precisely as the bread that is actively shared by Christ's friends; and it is eaten both as an anticipation of the communion of the world to come and as a memorial of the betrayal and death of Jesus. That is to say, it is also a sacrament of forgiveness; it is the risen Jesus returning to his unfaithful disciples to create afresh in them this communion of the new world. The bread that comes down from heaven is bread that is being handled, broken and distributed by a certain kind of community, the community where people recognise their need of absolution and reconciliation with each other. The community that eats this bread and drinks this cup is one where human beings are learning to accept their vulnerability and need as well as their vocation to feed one another.

So we can connect the prayer for daily bread directly to what goes before it as well as after it in the Lord's Prayer. We ask for the Kingdom to come and for God's purpose to be realised as it is in the liturgy of heaven, in the heavenly Temple, where our basic calling to love and praise is fulfilled. And in the light of that, we pray for today's and tomorrow's bread, for the signs among us of the future of justice and reconciliation, above all as this is shown in mutual forgiveness.

The Lord's Supper is bread for the world – not simply in virtue of the sacramental bread that is literally shared and consumed, but because it is the sign of a humanity set free for mutual gift and service. The Church's mission in God's world is inseparably bound up with the reality of the common life around Christ's table, the life of what a great Anglican scholar called homo eucharisticus, the new 'species' of humanity that is created and sustained by the Eucharistic gathering and its food and drink. Here is proclaimed the possibility of reconciled life and the imperative of living so as to nourish the humanity of others. There is no transforming Eucharistic life if it is not fleshed out in justice and generosity, no proper veneration for the sacramental Body and Blood that is not correspondingly fleshed out in veneration for the neighbour.

If, then, we are called to feed the world – recalling Jesus' brisk instruction to his disciples to give the multitudes something to eat (Mark 6.37) – the challenge is to become a community that nourishes humanity, a humanity on the one hand open and undefended, on the other creatively engaged with making the neighbour more human. 'Give us our daily bread' must also be a prayer that we may be transformed into homo eucharisticus, that we may become a nourishing Body. Our internal church debates might look a little different if in each case we asked how this or that issue relates to two fundamental things – our recognition that we need one another for our own nourishment and our readiness to offer all we have and are for the feeding, material and spiritual, of a hungry world.

As things are, we are liable to fall into a variety of traps. We may conduct our interchurch quarrels in a spirit that sends out a clear message of unwillingness to live with the other and be fed by them. We may consume our time and energy in what we like to think of as service to the needy, while ignoring our own need and poverty, especially our need of silence and receptivity to God. We may imagine that by faithfully performing the liturgy we embody the reality of the Kingdom, whether or not we are being transformed into a community of mutual nourishment. We may focus so closely on the rights of human persons that we lose sight of their beauty and dignity, the beauty and dignity that help to feed us. The list could go on. But the point is that the intimate connection between our mission and the prayer for our daily bread impacts at so many levels on the life of discipleship that the range of possible areas of failure is correspondingly broad.

The worst reaction to this would be simple anxiety. The best is to recognise that our vulnerability to failure is itself a reminder of our basic hunger, our need for each other. The bread of truth is also the bread of honesty about ourselves, and a church that is genuinely growing up into Christ will be one that is prepared to hear its judgement on these and other matters with patience and gratitude. So when we pray for our daily bread, we pray too for awareness of our failure, and – hard as this always is – for the grace to hear the truth about it from one another, and also from the wider world. For God can also act to nourish our humanity by the challenges and questions and rebukes that the rest of the human race puts to the Church.

6.

'Give us this day our daily bread' is thus a prayer for the fullness of the Church to be made manifest: in a pattern of recognising our own need and the neighbour's, and being able to turn with confidence to each other so that the need may be met; in the desire for the freedom to forgive and be forgiven; in the fuller understanding of the Eucharist as the centre of our Christian identity – not purely as a ritual act but as a foundation for community, a sharing of bread embedded in a practice of shared life, flowing out into the service of the world's hunger. It is a prayer, simply, for Christ to be our food and sustenance, so that all self-sufficient pride, all individual anxiety and defensiveness, all greedy effort to live at the expense of the neighbour are overcome; and the Church declares with clarity and conviction that there is indeed bread for the world's hunger to be found in the Body of the Lord. May that clarity and conviction – and the repentant self-awareness that goes with it – be always ours.

© Rowan Williams 2010