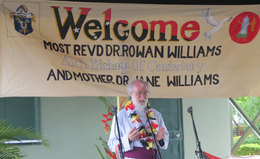

Archbishop's sermon on HIV/AIDS at Anglicare, Boroka, Papua New Guinea

Wednesday 24th October 2012

In his address at Anglicare in Boroka, the Archbishop said the Church should be committed to “boldness and openness” when speaking about HIV/AIDS, because challenging "stigma and discrimination" is the duty of all faith communities.The Archbishop acknowledged that significant medical progress has been made in treating HIV/AIDS. However, he stressed his conviction that treatment is never just about access to drugs. "It's a matter of access to people. It's a matter of access to counselling, access to friends, access to people who share the experience so that there can be a mutual process of healing".

This "humanising" of the situation is "one of the great things that Churches go on bringing to the struggle against the pandemic", said the Archbishop, who visited Papua New Guinea from 18 to 25 October.

The full transcript of the sermon is below.

Bishop Peter, distinguished guests, I am delighted to have the opportunity of visiting Anglicare this afternoon and I am very grateful indeed for the chance to look around, to hear something of the work you do, something of the experiences that you deal with.

Just before coming away to Papua New Guinea on this occasion, we held a seminar in Lambeth Palace on the subject of mental health, and one of the things which was discussed in that seminar was a poster campaign about mental health, which had to do with the fact that it was something very difficult to talk about. The poster, which had on the top, ‘Some conversations are difficult’ with a cartoon ‘difficult conversations’, and underneath ‘some conversations are not difficult’. And the point of this campaign was to persuade people that it’s not difficult to talk about mental health, even if everybody imagines it is. You can do it. And I thought of that this afternoon, because it’s quite clear that conversations about sexual health, conversations about HIV/AIDS are imagined by most people to be difficult, if not impossible. And because it is difficult for many people to talk about it, the sense of isolation and the sense of helplessness is intensified. It’s a kind of suffering twice over that is caused by that sense that it cannot be talked about.

Why can’t it be talked about? Because of the levels of stigma and discrimination that are around this subject. Now, all of you know better than I do some of the stories of how such a stigma and discrimination works, but when I ask what is the contribution of the Church can best make in responding to the challenge of HIV/AIDS in our time, part of the answer surely must be that the Church, all the Churches and indeed all faith communities, have to challenge stigma. They have to say over and over and over and over and over again, until people are tired of hearing it, that HIV/AIDS is not a cause of stigma. It’s not a matter of blame. It’s not a matter of people suffering the consequences of their own actions. It’s not a matter of people being a danger to the community. Again and again and again these things have to be said, said clearly, and said loudly. And said, I think in the spirit of one word in the New Testament which always strikes me with great force. A word that St Paul uses about the kind of speech that ought to be typical of Christians when they talk to God and when they talk to each other; and that word is boldness or openness.

The Church should be committed to boldness and openness in speaking about this, because only if we are consistently bold as Churches in resisting stigma and stigmatising discrimination – if I can put it that way – that is rejecting all possibility of discrimination, only so can we begin to break the deadlock that so holds back the possibilities that we now have in reacting to HIV/AIDS and the challenges it brings. Because the truth is that even within the last decade, immense advances have been made in treatment, and however difficult the situation is, we mustn’t make light of those advances. Far more people have access to anti-retroviral drugs. Far more people are able to talk about it, and far more communities of faith and other communities too are signing up to the agenda against stigma. We have moved, and the number of people now living with HIV/AIDS word-wide is some 33 million. It has ceased to be a death sentence. It has become something people can live with, and live with constructively and well, and even hopefully.

Now that is something that has developed over a relatively short period of time. When we first began to think about HIV/AIDS, I suppose thirty years ago now, there was an element of panic, even despair, and quite a lot of people said there was certainly a sense of the death sentence. We have moved so far. It can be done. So the question is, why isn’t it being done? Churches, voluntary organisations need to put their full weight behind the campaign to make accessible all the resources of medical science and personal care. And Governments need to hold on to the political will to make a difference. Sadly, many Governments, and many other organisations, have to some extent taken their eye off the ball in recent years. It’s become that little bit too familiar, and we’ve forgotten just how much of an advance has been made and therefore just how much difference can now be made when the political will, the medical and scientific resource and the popular awareness go together hand in hand to bring a message of hope to the people in societies where this is so much of a challenge.

I mentioned access to anti-retroviral drugs and comparable treatment a moment ago, but one thing that is brought home very clearly to me every time I meet people who are living with HIV/AIDS is that I meet people who have had traumatic experiences, because the one thing that becomes very clear to me is that the treatment is never just a matter of access to drugs. It’s a matter of access to people. It’s a matter of access to counselling, access to friends, access to people who share the experience so that there can be a real mutual process of healing that goes on, and I can’t underline enough how important that is in our whole response. No medical problem is just a scientific problem or just a technological problem. All serious medical problems are human problems, which is why medicine is a human science. We forget that at our peril. But in this area more than most, precisely because the curse of stigma, because of the fear of discrimination, it is all the more important that people should be given the freedom and the capacity to heal one another by listening, by sharing. Now, I have seen some of how that works here, at Anglicare this afternoon, and been profoundly moved and impressed by what you do in this way. I believe that this humanising of the situation is one of the great priorities, and one of the great things that Churches go on bringing to the struggle against the pandemic.

HIV is often both the cause and the result of violence, especially violence against women. Again and again, going round this afternoon, I have seen posters, campaign leaflets, reminding us that the campaign against gender-based violence is woven into our work about HIV/AIDS: we can’t tackle the one without the other. And I would hope with all my heart that the Churches here in PNG will give a united consistent voice in support of campaigns against gender violence, violence against women, the abuse of children, and all that goes with it. HIV/AIDS is enough of a challenge in itself. When it’s embedded in cultures of violence, disrespect and abuse, once again the suffering is doubled, trebled, magnified enormously. To keep those two things in focus, like the two lenses of a pair of spectacles is, I think, the challenge for the years ahead of us. We have risen – as a global community – we have risen quite well to the challenge of developing medical technologies to respond to the crisis. We have only just begun to realise how deep some of these problems are rooted in cultures of violence and cultures that despise and discriminate against women, and so I have had great hope in seeing how Anglicare keeps those two concerns firmly together. I have been deeply encouraged by what I have seen, of the possibilities that are opened up here, especially for women, to share, to talk about their experience, to begin to find the strength to heal others as well as themselves.

And once again, I believe Churches must continue all the time to pass ask themselves, are we doing what we can do? Are we doing enough to create that boldness and openness of speech, that trustful and safe environment where people can bring their challenges and know that they will be listened to and respected? And are the Churches doing enough to keep up the pressure on Government here and worldwide, not to lose focus, not to become bored with this issue, not to drop it because it’s a little bit inconvenient or a little bit embarrassing. The capacity is there; the vision is there, and I trust and I hope that we will all in the global community and especially in the Christian community step up to that challenge, confident that we have something vital to contribute in building trust, confidence in people, confident that God’s purpose can be served as we keep our focus on this, as we seek to create that boldness in the people we serve, as we seek to work towards a world where there is true safety and respect for all, men, women and children, those with and without HIV, those living with any kind of disability, those living under any kind of discrimination. We work for a world that is safe for all. Simple words but an enormously complex agenda. That’s why we need to keep on examining ourselves, refreshing our vision, refreshing our sense that this is indeed God’s call to us in our global situation today.

Thank you.

© Rowan Williams 2012