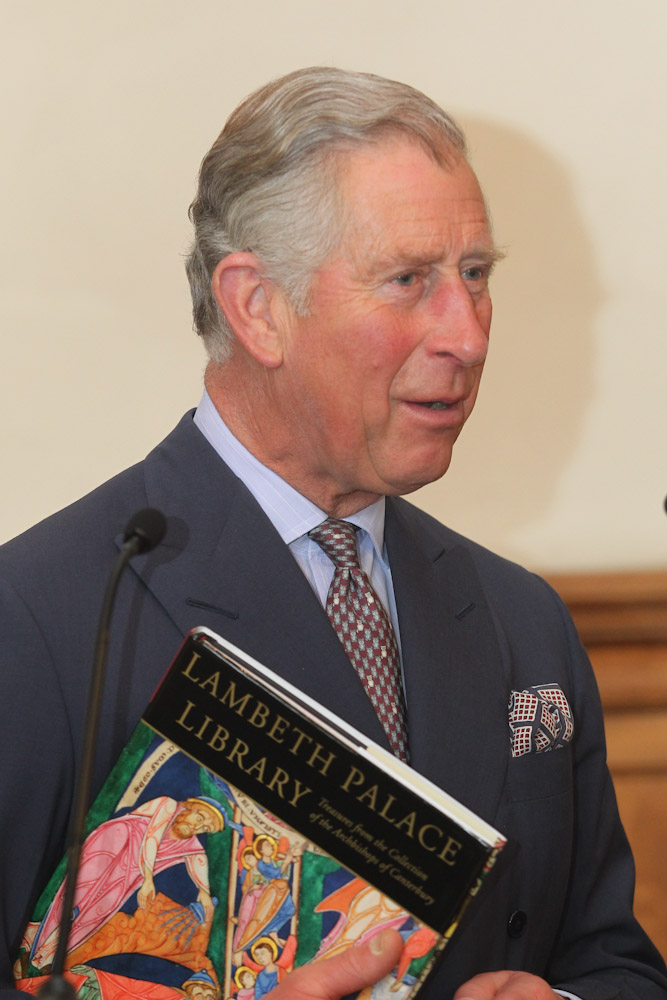

HRH Prince Charles opens exhibition at Lambeth Palace Library

Tuesday 1st May 2012

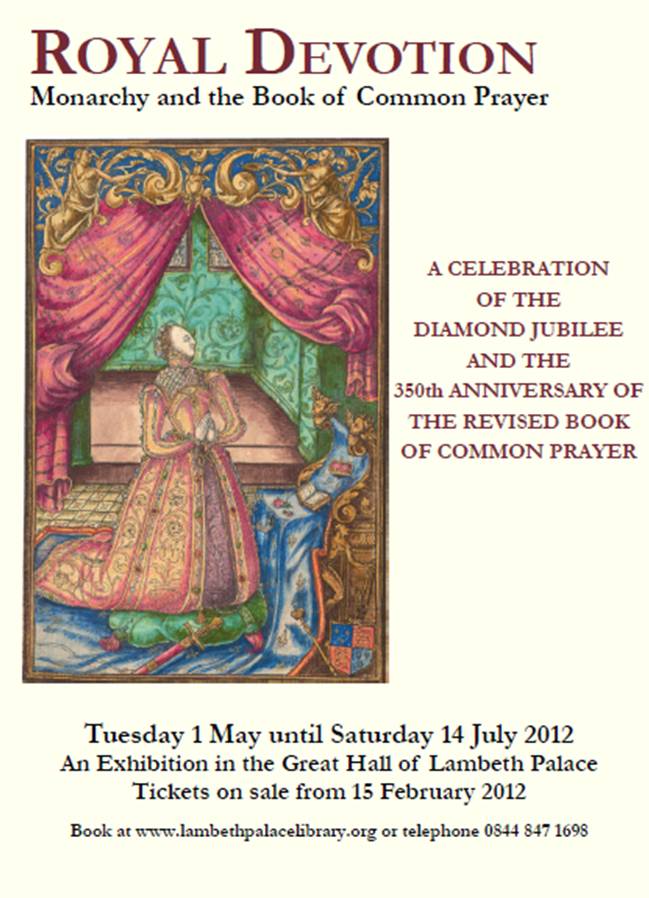

Archbishop Rowan Williams and Mrs Jane Williams welcomed HRH Prince Charles to Lambeth Palace to open a new exhibition at the Lambeth Palace Library.The exhibition, Royal Devotion: Monarchy and the Book of Common Prayer, traces the close relationship between royalty and religion from medieval to modern times. In particular tells the story of the Book of Common Prayer and its importance in national life.

Prince Charles was shown around the exhibition by the Archbishop and the curators of the exhibition, Hugh Cahill from Lambeth Palace Library and Professor Brian Cummings from the University of Sussex.

The Archbishop addressed with an audience of assembled guests [listen here, or read the transcript below] and Prince Charles replied [listen here or read the transcript below], paying tribute to the "beauty of holiness" in the Book of Common Prayer.

The Prince rejected reservations about the "accessibility" of the words of the 1662 edition of the Church of England's service book, saying its value becomes clearer as people grow older and experience more in life.

"As somebody who was brought up on that prayer book - day after day, year after year, Sunday after Sunday, school worship after school worship, evening prayer, communion, everything - those words do sink into your soul in some extraordinary way," he told a group at Lambeth Palace.

"One of the things I have never understood is why there is such an anxiety about accessibility when in fact, if we think about it, we all get older and we are not all 18 or 16 forever.

"Even though you may not understand those words at that age, it is only when you get a bit older and you have lived through life and had all sorts of experiences and you have suffered, and you have survived perhaps, that you then realise just how valuable those forms of words are, just how valuable the sense of the sacred is in our lives.

"And how, when you are up against it, and you have terrible moments to endure or overcome, whether it is being in war or faced with some appalling difficulty, or even facing death, then those words, those wonderful words, come back to you, if you have been lucky enough to have absorbed them over your lifetime.

"So I do think that sense of the beauty of holiness is something of enormous importance."

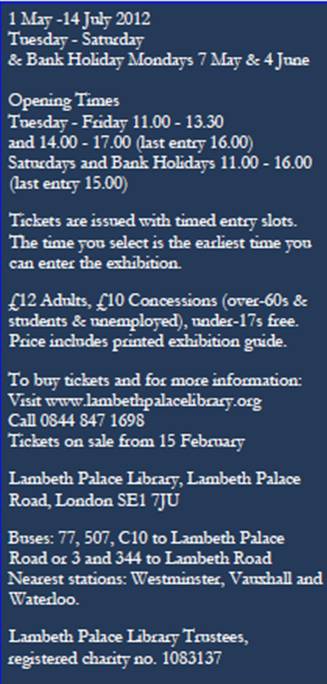

The exhibition runs from Tuesday 1st May until Saturday 14th July 2012. Further information, including how to purchase tickets, is available here or at the Lambeth Palace Library website.

|

|

Transcript of the Archbishop's speech:

Your Royal Highness, Lords, ladies and gentlemen, colleagues: my wife and I are really delighted to be able to welcome you, Sir, to this joint celebration of Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee and of the 350th anniversary of the Book of Common Prayer, as revived in 1662 after the restoration of church and monarchy.

Both of these events which we’re commemorating are significant milestones in the history of church and nation. They deserve to be commemorated and they give us an opportunity for thanksgiving and for reflection, which we greatly value. So it’s a pleasure to welcome all our guests here today, and to express publicly my warmest thanks to those colleagues who have worked so very expertly and very enthusiastically at putting together a wonderfully informative and enjoyable exhibition. And I want to particularly acknowledge the two co-curators of the exhibition, Professor Brian Cummings and Hugh Cahill for giving us such a wonderful collection of material. I hope you won’t think it inappropriate if I suggest we express our appreciation to Brian and to Hugh.

Just over two months ago, so we were honoured to receive Her Majesty the Queen and His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh here at Lambeth Palace, indeed in this room. And on that occasion, we had invited representatives of the nine major faiths in the United Kingdom to come together to celebrate the Jubilee and to share with Her Majesty some artefacts that represented important themes and values in their religious traditions.

It was an unprecedented gathering here within these walls, but it was one which certainly revealed the degree to which our society has changed quite radically in terms of its religious composition just within the past 60 years. It was an event which highlighted both the religious diversity of our society and the willingness to integrate, represented by the elements within that diversity.

Today though, Sir, we are looking at a different kind of theme. Not looking at the way in which our society has changed, but at some of the most significant elements of continuity within that society, represented by the history of our Book of Common Prayer, and by the interweaving of the life of the devotion of the Church of England with that of the monarchy.

You remarked as we went in, Sir, that it was in the year 2000 that you last visited a library exhibition and inaugurated the refurbished narthex outside the crypt downstairs, the oldest part of this building. And that was just prior to the opening of the palace to the public for the first time in the millennium year.

But on this occasion we’re particularly glad to be able to thank you for your active support of this exhibition, of the Prayer Book itself and indeed the Prayer Book Society, for allowing a Prayer Book

But to welcome you here also gives us an opportunity, Sir, to acknowledge your own commitment and focus in the wide variety of interests and good causes which you’ve championed with such enthusiasm and determination over the years. We want to acknowledge the great achievements of the Prince’s Trust, which provides such ample testimony of your concern for the young, the voiceless, the marginal and the disadvantaged.

Despite all the many commitments which press upon you, you’ve given tireless, imaginative support to many cathedral appeals, to the sustaining of the musical and choral traditions within our life of worship in the Church of England, to restoration and conservation projects connected with the church throughout the country, and in all these ways have testified to your own commitment to the continuity of the life of the Church of England – our continuity represented in the lively and creative life of so many parishes and cathedrals throughout the country. In the work that you’ve done for young people, you’ve expressed your own commitment to another kind of continuity – the continuity that wants to pass onto the next generation the deepest convictions and passions that animate our own moral vision through the Church of England. And your own deep attachment to the worship of the Church of England and the Book of Common Prayer are widely and warmly appreciated within the Church. So it’s particularly fitting to have you here for this great occasion and we’re very grateful that you’ve given the time to it.

The exhibition itself is, I think, a marvel of diverse riches in weaving together the life of the monarchy and the church over the centuries. It reminds us that the worship of the Church of England, represented in the Book of Common Prayer, is not in spite of all attempts to present it in this light, simply a minority interest rather on a par with train spotting. It is something which is woven into the kind of society we think we are and more importantly the kind of society we want to be. To celebrate this interweaving of the monarchy and the Prayer Book is a reminder that societies do not last or flourish unless they are able to say corporately, clearly, with conviction, what kind of society they want to be.

The history of the Book of Common Prayer is fairly complex. It is illustrated in all its complexity downstairs in the wonderful artefacts we’ve been able to bring together. It’s laid out with enormous clarity in Professor Brian Cummings’ wonderful new critical edition of the text of the Book of Common Prayer which we also celebrate on this occasion. And we’ll see downstairs some of those elements which fed into Cranmer’s great creative enterprise, not least a German Book of Prayer in the vernacular which represents something about Cranmer himself, first experiencing visiting Germany in the 1530s and discovering that it was possible to worship God in your own language – though I believe it was Thomas Elliott travelling within him who commented that the service in the vernacular in Germany seemed unduly long.

And while the Book of Common Prayer has represented that anchorage in the life of the monarchy, it can’t always be guaranteed that personal devotion spares you private dismay and failure. There’s a personal book of ours belonging to Richard III in this library which does not seem to have brought him a great deal of good fortune, though he carried it at the Battle of Bosworth.

We’re very proud of our library – very proud of the stories it has to tell, and very conscious also that the magnificent buildings in which the library is currently housed are for all their beauty not designed for the purposes of a modern library working at its best. These buildings were never designed to preserve and protect books to a high level of scientific skills. And the work of conservation, the work of maintaining the books in a properly controlled atmosphere is a formidable burden.

If we wish to be responsible custodians of the great heritage that we’re celebrating, we are bound to explore other possibilities. But I think I speak for most people in this room in saying that none of us would like to see this great heritage alienated from its historic home in Lambeth Palace and its historic association with the Archbishop of Canterbury. So we are beginning, very tentatively, to dig holes at the bottom of our garden. We’re beginning to look at the possibility of a new building in the Palace grounds which would ensure the proper conservation of this collection for future generations in the very best conditions that we can manage.

This would be a development which would allow for even greater public access to parts of the site, including the Great Hall. It would create opportunities for the public to become more familiar with the legacy that this building and the library represent. It would enable us to tell the story that we’re trying to tell in this exhibition and indeed all the many other stories the library has to tell. So I will shamelessly make a pitch for our hopes in this respect to create a library for the future which continues, maintains the very best of what we’ve received, and is a proper and worthy part of the legacy that the Church of England, Lambeth Palace and the Office of the Archbishop wishes to transmit to coming generations as part (to connect to what I said earlier) of that central moral and spiritual element in the life of this country.

Your Royal Highness, we are delighted you were able to be with us and to give us so much time, and as a small memento of this visit, I would like to present you with this little book of the Treasures of Lambeth Palace Library.

Transcript of HRH Prince Charles' speech:

Archbishop; ladies and gentlemen. Before I go, I know I’m here really to open this exhibition. But I’m also slightly hesitant, because the last thing I’m going to do is compete with the Archbishop, in terms of his brilliance at making speeches, or sermons.

And having witnessed when we went to the special celebrations around the Dickens anniversary, at Poet’s Corner recently, in Westminster Abbey, when the Archbishop went so brilliantly off-piste as to be quite remarkable; I don’t know how you do it. And it was the most wonderful lesson in Dickens’ relationship to religion, morality and everything else. And how your staff catch up with you, Archbishop, I do not know! But it was a remarkable tour de force, and I can only congratulate you.

But when it comes to the prayer book, ladies and gentlemen, I’m so pleased to have had this opportunity of joining you here today; seeing a little bit of the exhibition. Inevitably I never had enough time to get round all those fascinating exhibits. And having been educated a little bit at Cambridge, I could tell at once that the exhibition had been organised by a former undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge. And Professor Brian Cummings has done a remarkable job, I think.

Having looked a little bit at his book, on The Book of Common Prayer, I was also fascinated to discover a little bit more of the history behind all this. Because what so many of us, who are rather ignorant, never seem to understand is just how much argument and conflict went on ceaselessly about how to devise a prayer book which suited most people. So it would seem that the 1662 version was a remarkable exercise in compromise.

As Professor Cummings put it, there are a few enthusiasts and die-hards left who actually do rather appreciate that Book of Common Prayer. And as somebody who was brought up on that prayer book, day after day, year after year, Sunday after Sunday, school worship after school worship, evening prayer, communion; everything, those words do sink into your soul in some extraordinary way.

And one of the things I’ve never understood is why there is such an anxiety about accessibility, when in fact if we think about it, we all get older, and we’re not all 18 or 16 forever. And that even though you may not understand those words at that age, it’s only when you get a bit older, and you’ve lived through life, and had all sorts of experiences, and you’ve suffered, and survived, perhaps, that you then realise just how valuable those forms of words are. Just how valuable the sense of the sacred is in our lives. And how when you are up against it, and you have terrible moments to endure or overcome - whether it’s being in war, or faced with some appalling difficulty, or even facing death - then those words; those wonderful words, come back to you, if you’ve been lucky enough to have absorbed them over your lifetime.

So nothing could give me greater pleasure than to open this exhibition, ladies and gentlemen.