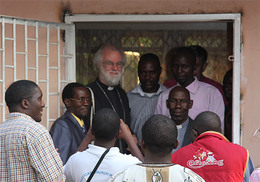

Archbishop addresses Zambian Clergy

Wednesday 12th October 2011

The Archbishop delivered a keynote address to the Zambian national clergy conference held in the Mindolo Ecumenical Foundation, on the Challenges to and opportunities for growth in the Anglican Communion.Making reference to the contribution of Richard Hooker to Anglican identity in the sixteenth century, the Archbishop highlighted the enduring insight within the Anglican tradition of relying not on a single authority within the Church but on a commitment to reciprocal discussion, so as to learn from each other's wisdom in order to discover the widsom of God.

The unity of the Church amidst its diverse expressions worldwide depended, he argued, on relationship rather than regulation. He outlined four areas requiring special focus:

- real excellence in theological education rooted in the different contextual realities around the world;

- use of communication which reflected the mind of Christ, “Holy Communication”;

- authority expressed as the willingness to stick with our fellow Christians during disagreement, such as through the commitments to common discernment made voluntarily in the Anglican Covenant;

- a more co-ordinated approach to development, through a common social vision of what the kingdom of God might look like expressed in love and service.

While not creating instant agreement, such approaches he hoped would enable the Church to grow in faith and mutual recognition, offering a vision of community through prayer and deepened relationship.

Read the transcript of the address below.

Address by Archbishop Rowan Williams

to Zambian National Clergy Seminar

at St John’s Theological College, Kitwe, Zambia

First of all thank you very much for the opportunity of being here with you this afternoon, which I hope is not simply an opportunity for you to listen to me but for me to listen to you. I don’t (in spite of the programme) intend to speak for an hour and a half, but I want to share some thoughts with you which I hope may encourage you, whether you are Anglicans or not, to ask some questions. Because I believe that many of the problems and challenges facing our Anglican communion are in fact problems that in different ways face every Christian family at the moment. In a little while I will spell those out further.

But I hope you’ll forgive me if I begin by speaking for a while about what I think the Anglican identity truly is. What is it that first prompted this particular expression of Christianity? You’ll know something of the history of the sixteenth century in England – a Reformation in England, which at the end of the day became neither Lutheran nor Calvinist but followed a line of its own, which no one has ever quite been able to define since.

But at the heart of this, there were I believe two or three very important preoccupations. The first was the idea that the laity of the Church, as represented in those days by the monarch and the government, had a significant role in the actual governance of the Church. While that may seem very strange to us now in the way it was expressed, it was in its own context an important affirmation. A church which had been dominated by a very distinctive clerical group, the celibate clergy of the medieval Catholic Church, that church was about to become something different – a church governed for certain purposes by the assembly of the nation, the society itself (taking for granted that that society was Christian of course).

Now that was revolutionary in many ways, and some of the expressions of that revolutionary newness were not pleasant. The reformation period was not an easy or an edifying period. Terrible things were done by Catholics to Protestants and by Protestants to Catholics, by Protestants to other Protestants and by Catholics to other Catholics.

Nonetheless, that revolutionary idea that the church did not need to be governed by a corporation of celibate clergy was crucial to the Anglican experiment. But because it was revolutionary, and because there were concerns about losing roots and continuities, the Church of England at that time laid great stress on certain sorts of visible continuity. It continued to ordain the bishops, priests and deacons in the old style. In its prayer book, it preserved many of the treasures of early Christian and Medieval devotion, many of them of course rewritten in English by that great master of the English language, my predecessor Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

That emphasis on continuity was not always appreciated in the sixteenth century by either side of the Reformation divide. Those who still wanted to identify themselves as Catholics, said there wasn’t enough continuity - there was no continuity in obedience to the Pope, no continuity in the principle of celibacy, no continuity in many of the outward forms of faith.

On the other hand there were Protestants, convinced and sometimes rather fanatical Protestants, who said there was too much continuity. If you look at an Anglican minister officiating at evening prayer, he looks suspiciously like a Catholic priest. He’s wearing a long white gown, which extremists of the day described as a ‘Popish rag’. Too much continuity: continuity in some aspects of devotion to the Holy Communion, the Holy Eucharist, continuity in infant baptism, and continuity in another and rather more subtle sense, which is I think very interesting.

That other kind of continuity is expressed quite movingly in a controversy that took place in London in the 1580s between two famous Church of England preachers. They both had a job in the same church. One of them was a very straightforward loyal Church of England priest. The other was a very convinced, very learned and eloquent Puritan. They worked in the same church, and every Sunday, apparently, whatever you heard in the sermon in the morning would be contradicted by the sermon in the evening.

But what provoked the greatest controversy was the suggestion by one of these preachers, the one who was more obviously a mainstream Church of England man, that not every Roman Catholic would go to hell. That was quite a radical idea in some circles at the time.

This man, whose name was Richard Hooker, said: for centuries our fathers and mothers in the faith have done the best they can. They’ve had the wrong ideas about many things, so we believe, but they’ve struggled to be faithful. We cannot say that before the Reformation there were no true Christians, and even now we cannot say that outside the Reformed Church there are no true Christians. A Roman Catholic may go to heaven.

Well, if he was saying that at eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning, by four o’clock on the Sunday afternoon his opponent, Richard Travis, had said exactly the opposite – that it was absolutely essential to believe that all Roman Catholics went to hell, and probably on his way to hell with them was the preacher of the morning.

They were robust days of theological argument.

But the point I’m making is that Richard Hooker, like many in the Church of England at the time, believed in a continuity that was not just about ministry or sacraments, but was actually a continuity of community. Our fathers and mothers in the faith may have been mistaken, but they’re still part of one body with us. Those who don’t want to identify with the Reformation now in the sixteenth century, we disagree with them strongly and yet we may find ourselves standing together in the grace of God.

And I believe that continuity is one of the really profound things about the Anglican legacy. We as Anglicans have often prided ourselves that we preserved the apostolic ministry of bishops, priests and deacons, but I think perhaps a better cause for pride is the fact that we preserve that sense that it was possible for Christians to disagree and yet belong in one body.

I want to say just a little bit more about Richard Hooker - and I hope you’ll forgive me for this but he is a great enthusiasm of mine, as you’ve probably guessed already. Hooker was a scholar trained at Oxford. He spent much of his life as a parish priest. He ended his life as a simple country pastor just a few miles away from Canterbury. He published very little in his lifetime, but after his death the great mass of his important work on the Church saw the light of day and has ever since then been a major source of inspiration for Anglicans. Now I could talk at length about the theology of Richard Hooker and it’s very tempting to do so, but I want to single out one or two passages that are not perhaps all that well known.

Hooker has a great deal to say about wisdom, about how God deals with us in wisdom and how our faith has to absorb the wisdom of God. And wisdom in the Bible is the principle through which God holds things together – holds diverse things and persons together in harmony and interaction. If you read the book of Proverbs, if you read other ‘wisdom books’ in the Old Testament, if you read some passages in the book of Job, you’ll see how the wisdom of God is understood in that way. It holds things together.

And that is, you might say, a theme on every single page of Hooker’s great work. But he illustrates it beautifully in two passages where he brings this very much down to earth. He is writing in response to criticisms of the Church of England from those who call themselves Puritans, those who are very very strong Reformed Christians, who believe that the Church had to start all over again. One of the things that some of these Puritans disliked was music in church. Hooker gives himself a long and rather wonderful passage about this. (I have to say, no Puritan would survive five minutes in Africa, that’s clear.) But Hooker asks, why do we have music in church? He answers by pointing to the practice of the Anglican Church at that time of singing the Psalms, one side of the church and then another in alternation. And he says, that is a picture of the Christian life. We’re singing together and yet we’re singing in conversation. One side speaks, the other side answers. And that meeting of voices, as we sing, is a visible and audible sign of what the Church is like.

I think that is a wonderful image, that the Church is musical, that music expresses something completely essential in the life of the Church because it is many voices coming together – many voices, one answering the other. You don’t even have to think of the two sides of the choir in a great cathedral, you just think of the way in which, so often in music, a voice answers another voice and there is a kind of dialogue going on.

And then there’s another passage, where he speaks about how we read the Bible. Again, he’s responding to opponents, to critics. He’s responding to people who say: the Bible is the book of the law of God, everyone can agree with that, and that means that anything that is not mentioned in the Bible must be forbidden. Which of course rules out quite a lot of things that happen in church, and indeed elsewhere too.

Hooker says the Bible is indeed the book of the law of God, and law is essential for human life. But law works in many ways, and is discovered in many ways. And it’s simply not the case that the Bible is just a book that drops from heaven and is given into the hands of an individual to open it and find the answer. No, he says, no one of us alone is able to read the Bible properly. We need one another to read the Bible. And in his sixteenth century English, he says it is because of our ‘common imbecility’ that we need one another to read the Bible. In other words, we’re all more or less stupid, and therefore when we come to read the word of God we need each other’s wisdom in order to discover the wisdom of God.

So the Bible is not just a book dropped from heaven and opened by an individual, who looks up the index, finds the answer, and puts it back on the shelf. The Bible is a book through which God invites us to discover him again and again. It’s a book of authority. It is indeed a book beyond which we cannot go, we can’t teach or say things that are just contradictory. But discovering what it really means, that takes time and wisdom. And most importantly of all it takes a neighbour, a Christian neighbour, to help you.

I found a quotation a few months ago from a Canadian poet [Robert Bringhurst], who was talking about a particularly difficult poem with three different parts to it. He said “To understand a poem like this, you might think that what you really need is three heads. But”, he said, “I’d rather say that what you need is two friends.” And the Christian approaching the reading of the Bible needs two or more friends. We do it together.

I picked those two passages from Richard Hooker’s enormous book to show you some of the ways in which he thinks a healthy church should work. This sense of the musical coming together of different voices; this sense of our need for one another to discover what the Bible is really like. And, at its best, I think that the Anglican tradition has carried those two insights through the centuries. There has been some real commitment to mutual, reciprocal, two sided exchange and discussion. We have never had a single authority that finishes every debate just by saying so. Some people think the Archbishop of Canterbury is that authority, or should be that authority, but I’m very relieved that he isn’t and I don’t believe he should be.

So that is some of the heritage which I think Anglicans bring to share with the worldwide Christian family. I think it is expressed in a number of ways. Over the centuries it has been expressed in a particular attitude to scholarship, especially Biblical scholarship. There was a great classical period in the nineteenth century when, especially at Cambridge in Britain, a number of Anglican scholars took some of the best of what was coming out of Germany in terms of scholarship and (as you might say) brought it back into the life of the Church. Westcott, who became a great Bishop of Durham, and his friends Joseph Lightfoot and Fenton Hort, worked together establishing the best text for the New Testament and writing very profound theological commentaries on scripture. And Bishop Westcott very famously said, and I think it’s a wonderful motto, God gives us work to do in the Bible. He invites us to work. When a passage of the Bible is before us, even if it looks simple, God wants us to stretch our minds and our hearts, to go on being willing to learn as we read.

And that’s a great principle. I think also it’s true that Anglicans through these centuries have very often wanted to say that their theology is best expressed in the prayer book and in hymns - not in text books, but actually in the language of worship. For a long time people were able to say if you want to know what is important in the life of the Church of England, read the prayer book. And although the Methodists took off much more dramatically than we did in writing and singing hymns, remember that Methodists did start as Anglicans – and the reason they’re Methodists is that the Anglicans were so terrible to them in the eighteenth century. But Methodists and Anglicans alike found that it was the language of hymns that best expressed what the theology was.

Now all of that is a bit of history – it’s trying to give a bit of a picture of where the Anglican tradition comes from. It’s a tradition which for many centuries was mostly present in Britain, a little bit in America and not very much anywhere else. Then with the expansion of the British Empire and a number of other factors, the Church of England found itself, much to its surprise, beginning to exist in other places as well. At first when it existed in other places, it simply acted as a chaplain to English settlers and soldiers, but once again without quite noticing how, it found itself attracting others and having to find out about the culture in which it lived. It did that sometimes very slowly and very unsuccessfully. It’s still trying, and I’m glad that it’s still trying.

All of that may help to explain why when you look at the Anglican Communion today (and I’m moving onto the second part of what I want to say) you will see quite a bit of variety and indeed quite a bit of tension. The history that we have means that we were never likely to have one great global organisation that made sure that all the rules were kept. We have developed as a family of local churches, of thirty-eight provinces, culturally very very different - ranging from the Church of England, the ‘Mother Church’, to the United Churches of South Asia, which although they are a marriage of Anglican and non-Anglican elements are also a full part of our family, and the Church of the Province of Central Africa - central of course in the whole Anglican family.

But it does mean that the challenges that we have as Anglicans worldwide are going to be quite considerable, because we do not have, immediately, a mechanism for solving our problems globally. If you are a Roman Catholic you do have such a mechanism in the shape of the Pope in Rome. Other churches have varying degrees of international global organisation. But we are quite deliberately a family of self-governing churches.

And yet we are a family of self-governing churches for whom it matters enormously that we are a family, that we recognise one another, that we share the same kind of ministry, the same - broadly the same - kind of worship, and therefore the same kind of theology.

So the challenge, the basic challenge, for being an Anglican in these days is how to preserve the diversity and independence of our local churches, while at the same time preserving the family resemblance, preserving our ability to recognise one another. Because it’s only when you recognise somebody else that you can actually have a real conversation with them. And going back to Richard Hooker’s analogy of music, you need at some point to know that the other person means roughly the same thing you do, by being in tune.

One implication of that is that the unity of the Anglican Church is always going to depend very heavily on relationship rather than regulation. And at the present moment when we have such a lot of tensions in the global communion, there is a strong temptation to say we need regulation. Yet most people when you press them will say “We really need better relationship” – because only when our relationships are better do we respect one another sufficiently to work together.

I want to touch on four areas of challenge and opportunity in the life of the Anglican family today. These, to my mind, are the areas where there is most hope and also most possibility of things falling apart.

I will begin, appropriately in this place, with theological education. The fact that our family consists of so many different self-governing provinces does mean that we’re not able always to impose a single policy or practice about theological education right across our communion. Unfortunately that sometimes means that there are parts of our Communion where theological education is not at its best, where sometimes clergy are not trained to the same level of education as some of their own flock. And I think this is a tragedy, because as people in general become more and more educated and literate, it’s very important for their pastors to be able to deal with them. If one of your people comes to you and says “I have this problem” and all you can say is “I’m sorry, I don’t understand” then perhaps that’s not the best way of dealing with the life of the Church.

It doesn’t mean that everyone has to become a scholar and an academic. It does mean that every church, every local bit of the Anglican Church needs to take very seriously the question, how do we give the best kind of education to our pastors? How do we allow them to grow to the full extent of what they’re capable of, so that they can indeed sing with the understanding as well as the spirit.

In recent years the leaders of the Anglican Communion have sponsored a project around theological education which has drawn together people from around the globe in some very creative ways. This project has resulted in setting out a number of statements, listing the kind of things – the kind of expertise – that a deacon, a priest, a bishop, might need and indeed that a layperson might need. I feel very grateful that we’ve had the services of so many gifted people in that project.

But for it really to take root we need, I would say, far more investment of resources in theological education and far more centres of real excellence right around the globe. We can’t indefinitely assume that if somebody wants a high quality theological education they need to go to England or America or Singapore. I think our local churches need to be working harder and harder to guarantee real quality, real excellence, in their own context. And that’s why I’m deeply grateful that the Church of the Province of Central Africa is now giving such clear attention to this question.

So that’s the first area, theological education.

The second area I want to touch on is communications. The challenge here is, of course, that everybody knows everything straight away across the globe. Thanks to electronic communication you can find out what’s going on in Papua New Guinea, in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne and Vladivostok by just clicking a button. The trouble is that global information doesn’t always tell you real truth. It may sometimes tell you what’s going on, it doesn’t necessarily tell you what it means. And quite often, of course, it doesn’t even tell you truthfully what’s going on.

In recent years, as you know, the Anglican Communion has had endless controversies over sexuality. These have been made even more difficult than they need to be by the fact that people have written extensively, inaccurately, sometimes even violently, about each other on the internet and have poisoned the possibilities of real discussion and mutual understanding. I think this is again a real tragedy.

Professor David Ford of the University of Cambridge likes to say that if we believe in Holy Communion, we ought to believe in holy communication. That is to say, the way in which we communicate with each other should be holy. The way in which we talk to one another should be holy. It should reflect our allegiance to Jesus Christ, our valuation of life in the body of Christ, our seriousness about the life of the Holy Spirit. And so often our communication, especially in recent years, has become unholy, unloving, unspiritual. We need real communication, we need to know what’s going on, yes. But again we need the relationships within which that communication makes sense and actually builds us up instead of surrounding us with anxiety, unhappiness and prejudice.

So: theological education, communication, the need for high quality theological education in every context, the need for holy communication, the need to learn how to talk to each other as responsible, grown-up Christians.

The third challenge is in some ways the most difficult of all. And it’s a challenge in the area of power and authority. As I’ve said, some people think that there is a quick answer to our problems if only somebody had the power to shut down an argument and settle a question. That’s where, as I say, the Archbishop of Canterbury sometimes gets looked to by people who think that he ought to be doing it.

Another great Anglican theologian about a hundred years ago, a priest called John Neville Figgis, once said about the Church that one of our troubles is that we often think the only real authority is the authority of a policeman - the only real authority is the authority of somebody who can come along, brandish a big stick and make sure you do what you’re told. But he asks, is that the authority that Jesus exercises in the Gospels? Well no, and yet ‘all authority in heaven and on earth’ is given to the risen Jesus. How does he exercise authority? He does it, it seems, by being who and what he is. He does it in love. He does it in the extraordinary faithfulness that he shows to those who want to run away from him, or reject him. That’s authority as Jesus exercises it.

And the challenge for all of us – and I mean all of us, especially my brothers and sisters in the pastoral ministry – is to re-think our authority as the authority to go on being with people. The authority to stick with our fellow Christians, even when it would be much more comfortable to have nothing to do with them.

There are days in my life (and I’m sure there are days in your lives) when you wish that most other Christians would go away, and I’m afraid that there are probably days in the lives of most other Christians when they wish that you and I would go away. But the authority of Jesus is his freedom to stay there and not to give up on those he loves. Can we understand authority in that sense? Because this is, in some ways, at the heart of our disagreements at the moment.

Some parts of our Anglican communion, as you know, especially across the Atlantic, have taken revolutionary steps in approving same sex relationships, in spite of the advice given by the Archbishop of Canterbury and all the other bodies that represent the global family. They have deliberately decided to be a minority, you might say, and that has strained relationships to breaking point.

People in other parts of the world feel “if they take that decision then I’m somehow involved in it, but nobody asked me about it”. And that’s very hard. Yet I don’t believe the answer is just to break things apart. Here is a real disagreement, a real source of tension. Here is what in some people’s eyes is almost an abandonment of biblical teaching. And yet our brothers and sisters across the Atlantic still read the same Bible and pray to the same Father. Somehow, I believe it’s worth working to see if we can go on recognising one another, even across those gulfs. It doesn’t mean we approve or agree, but the relationship still matters.

As always the question of authority is very much tangled up with the question of power. Very often people in Africa and Asia will look to the churches in North America or Northern Europe, and say “For generations you’ve had the power. You’ve had the economic power, the political power, you’ve been telling us what to do. And here you are again telling us what to do, or telling us what’s right and wrong.” I think that dimension of power in our international debates is a very important one. Someone who’s very eager to push forward a change in England or America might need to remember from time to time that for somebody in another context, in Africa or in Asia, it can feel like yet another bit of imperial power being exercised.

So that’s why in recent years we have been working hard in the communion to see if we can find a way of voluntarily, freely, expressing our willingness to live together. The text that’s circulating at the moment, the Anglican Covenant, is an attempt to give some kind of structure to that. It’s a text which lays out the common faith that unites us, that makes us recognisable, and that lays out a possible way of resolving disputes.

It’s a text that assumes we are capable of self-restraint. Rather than just going ahead with what seems right to us, we share it with the whole body and try and find discernment in that way - which is really, isn’t it, just another version of what Richard Hooker said about reading the Bible. We need to be reading and thinking together. And I hope that if the Covenant is approved by our provinces, that will quite simply give us a way of reading together and thinking together and so rebuilding relationship.

My fourth and last area of challenge and opportunity is a very much more practical one, and that’s to do with development. The Anglican churches throughout the world have played a very significant role already in education and healthcare in the grassroots care of communities. The Mothers’ Union plays an extraordinary role in the Communion by the work it does in raising the awareness and the skills of women. You don’t need me to tell you that in this country and in this continent and throughout the world, skilled, confident women are so often the key to better education and healthcare for everyone. I think that cannot be stated too strongly, and it’s one of the great glories of the Church in Africa that it has done so much for the status of women in that respect. I pay tribute, very gladly, to the Mothers’ Union in that context.

A few years ago on returning from a visit to Burundi, I wrote an article for one of the newspapers in Britain on what I’d seen in Burundi and, not by my choice, the newspaper gave this the headline, “How the Mothers’ Union is riding to the rescue of Africa.” It’s a fine phrase and I’ve often thought of it. It conjures up a wonderful picture in the mind. But that means that part of our identity, in context after context across the world, has been and is this commitment to the good of the whole society around. Not just the care for our own people but commitment to the good of everyone – again, one of the principles which, in Britain, was part of the original vision for the Church of England.

So again, to talk about recent developments in the Communion, many voices were raised at the last Lambeth Conference of Bishops in 2008 saying we ought to have a more unified, a more co-ordinated approach to our development work across the communion. That was reinforced by the Anglican Consultative Council and by the Primates of the Communion. So very recently we have been able at last to put together an Anglican Alliance for relief and development, which does not seek to be another big global NGO but tries to join up the work that is being done - to make sure that there isn’t duplication; to make sure that best practice is shared; to make sure that we have a sense of priorities in our giving. I think that will be one of the things I shall look back on with greatest gratitude in my time as Archbishop, that it has been possible for that Alliance to take off and to begin its work with a number of important regional consultations. It is served with great skill and dedication by some very high quality people.

And it’s as we work together in the service of the whole community - working for the empowerment of women, working against violence especially gender violence, working with those with HIV or Aids, working with (and I saw this in Congo recently) those who’d been child soldiers, working to develop sustainable agriculture, all of those things - working in those ways is part of what it means to be an Anglican. It is one of the things which holds us together in a common social vision, even when we disagree over other things. A common vision of what the Kingdom of God might look like in love and service.

So there are four areas where I believe our Anglican communion worldwide has great challenges but great possibilities.

Theological education - the need for excellence in theological education, whatever the context. Not necessarily the same kind of excellence everywhere, but the best that can be done in this place and this place and this place. If we don’t have that, as I say, we lose our pastoral skill, our lay people are going on ahead of us, and we also lose the ability to think carefully together.

Communication - holy communication. Making sure that we check the way we talk to each other and about each other against the mind of Christ.

The right approach to authority - not looking for someone to step in and exercise power to close down an argument and make everybody think the same way, but an understanding that real spiritual authority comes from the willingness to stay with the neighbours God has given us.

And development - making sure that before us there is a coherent, powerful, persuasive vision of the Kingdom of God, that sets us together working for the good of our neighbours, for the common good of our society, whatever our disagreements and tensions may be.

There’s a great deal more that I could say by way of illustration of our present situation, but I hope that those four points may give some foundation for questions and discussion as the afternoon goes on.

Before I finish, I want to go back to the beginnings, back to Richard Hooker. Hooker was arguing for a church that did not exercise political power and yet had an absolute commitment to the good of society. Hooker was arguing for a church which did not have one single Papal figure to sort out questions, but he was also arguing for a church deeply rooted in the wisdom, in the doctrine, of the centuries and deeply rooted in painstaking patient labour in reading the Bible. Hooker was arguing for a church in which you didn’t immediately want to see total agreement about everything from everybody, but he was also arguing for a church in which people went on growing in their faith, to the point where they could indeed see the face of Christ more clearly in each other.

Hooker was arguing for a ‘musical’ church - a church where, perhaps rather slowly and with a lot of effort and a lot of false starts, eventually the voices might just come together. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the experience of trying to find out what the harmonies are when you hear a tune or sing a tune for the first time. I have something of a history of singing over the years and I always like to sing in harmony when I can. But that means if I’m singing a hymn tune that I’m not familiar with or haven’t heard before, I’ve got to try and find what the harmony is if I don’t have the music in front of me. And that means that I’ve got to go on listening rather carefully to what everybody else is singing. Sometimes I make horrible mistakes, and anybody standing next to me will shudder when they happen. But at the end of it all, I hope that I’m growing into harmony, that after six or seven verses I may be beginning to get a sense of what the bass part might be for this tune, and not come up with appalling discords.

I think Hooker would have understood what that was about. I think he hoped and prayed that, in the church he believed in, we would be growing into harmony. Because above all, he saw the Church not as an assembly of individuals doing their own thing and occasionally meeting with a rather distant politeness, he saw it as essentially a community in which everyone depended on everyone else and everyone was constantly learning from everyone else. It’s a very ambitious vision of the Church, but I don’t think we ought to be ashamed of it. It is a vision which demands of us a great deal of patience and a great deal of imagination, and I don’t think it is any the worse for that.

Whether you’re Anglican or not, those are some of the themes which I think belong to the Anglican identity these days, and some of the insights which the Anglican might want to offer to fellow Christians of different traditions. As I said right at the beginning, we’re not unique. Anglicans have problems that other churches have; we’ve had them in recent years perhaps rather more publicly than many others. Other churches have the same issues about harmony, about international, intercultural disagreement, about power, about the anxiety that comes when you see other people apparently driving an agenda that you’re not happy with.

So it’s not as if we alone have problems. Sometimes I’m asked in interviews or whatever, “Isn’t it terrible that the Anglican Church is so divided – what are you going to do about it?” And all I can really say is “Well we’re not the only church that’s divided. And what I’m going to do about it, is what I think any Christian ought to do about it, which is to try and pray harder and grow into deeper relationship.” And while that may not be a slogan that immediately answers the questions that journalists might want to ask, I think it’s a pretty good one. I hope you do too.

© Rowan Williams 2011