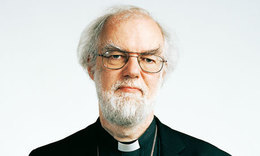

David Hare interviews Archbishop

Photograph: Spencer Murphy for the Guardian

Photograph: Spencer Murphy for the GuardianSaturday 9th July 2011

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, was interviewed by writer and director David Hare. The following article was published in the Guardian newspaper.Rowan Williams: God's boxer

The Archbishop of Canterbury talks to David Hare about taking on the coalition, the atheists – and why life isn't like a Woody Allen movie

In 2002, when visiting Manhattan, I was surprised to find a photo of Rowan Williams pinned proudly on the fridge of my two best friends. As they remarked at the time, "Who'd have thought a couple of New York Jews would have a Welsh churchman for a hero?" It was just at the time when Williams was about to be enthroned, and from 3,000 miles away they had already noticed that at last we had a public figure in the west who was something other than an easy object of contempt. Better still, once taking up office, he might have some interesting things to say.

It is so deep in the nation's prejudice to believe that the Church of England is weak and wishy-washy that the thoughtfulness and radicalism of this Welsh poet and priest tend to get overlooked. Even when, early last month, he edited the New Statesman and made some clear-sighted observations about both the coalition and the Labour party ("We are still waiting for a full and robust account of what the left would do differently"), the rightwing press couldn't stir itself to offer much more than a routine lather. Williams often speaks in public in a regulation-issue churchy voice, so tone can tune out content. But this is a man, remember, who in 1985 was arrested during a protest outside the US air base at Lakenheath. What was his offence? He was singing psalms.

The only time I had met Williams before this interview was for a Newsnight discussion during the 2008/9 banking crisis about which the archbishop had been notably eloquent: "Every transaction in the developed economies of the west can be interpreted as an act of aggression against the economic losers in the worldwide game." Williams came upon me in the make-up room. I was waiting for Paxman and passing the time by writing my diary. When he asked me about its contents, I admitted it was the usual unattractive mix of whingeing and self-pity. I said I thought that his own diary, recording his fractious years as archbishop, would be far more interesting. Did he keep one? He said he didn't, but that he feared, if he had, it would have been pretty much like mine.

Even at the time, I thought this an odd revelation. Like Barack Obama, Williams seemed a good man dealt an impossible hand. If you had happened, at any point, to follow the unending rows about gay clergy and women bishops, then it was obvious that the archbishop had endured a great deal from some insufferable oafs in the higher reaches of Anglicanism who had always been ready to pretend that their lack of Christian kindness towards colleagues was somehow justified by faith. A friend of Williams had even described his period of office as a crucifixion. But even so, I had read enough of his distinctive theology to know how strongly he felt that Christianity should be an escape from self, not an indulgence of it. "Jesus," he had written, "is the human event that reverses the flow of human self-absorption."

So for me it was a great privilege to be able to question him properly, this time by strolling down Miss Havisham's draughty corridors all the way to his vast study in Lambeth Palace. It's hard to believe that such an enormous room can be overwhelmed by files, papers, candles and icons, but it is. If the archbishop's echoing, cavernous mind sometimes seems to resemble this room, then that's because he's both prodigiously learned and, perhaps to the frustration of his admirers in New York, now also considerably more guarded. "I know some people may find this rather difficult to believe, but I just don't see myself as an individual public commentator. The first thing is to try and hear what's not being said and weave that into the public discourse. Of course there are occasions when, as a teacher, I do want to say what I think about the ideal social order, but the tar-baby morass of argument about what I think myself is not a place I want to go. After half an hour of wrestling with the tar-baby, you're immersed in the tar. Things get lost."

I point out that in aiming solely to give voice to the voiceless, he sometimes seems reluctant to draw some very obvious conclusions. To me, for instance, a political editorial that asserts, "We are being committed to radical, long-term policies for which no one voted" is implicitly accusing the Conservative party of deceit. Surely we all know Tory politicians went into the election with one agenda, and dishonestly started implementing another? Why doesn't he say so? "No, I genuinely don't think it was a deceit. In a coalition, policies get pooled. And there was a degree of, 'We've got to sort this financial question out quickly, and if that means radical cuts, radical restructuring, then we'll do it. Whatever the cost.' I wouldn't even call it breach of trust, because again, that suggests there's a line of betrayal. I really, really don't think it's that. But I do think the marriage between a localist agenda and a difficult financial squeeze means people don't feel able to see these changes as a vision of the former. They see it as the latter.

"The 1944 Education Act isn't the Law of Moses, but there's something about it that says we need to have a coherent national policy for the delivery of standards. We need to have the kind of system that supports the less advantaged. Now the sense in some of our schools is that things are going a lot more quickly than is comfortable for people to feel confident. You can unravel things, but they will take a long time to put back together."

The archbishop is clearly resigned to the inevitability of being misrepresented ("Did you know the editorial would excite the press?" "I had a shrewd suspicion." "Are you now immune to it?" "Not entirely, but I'm inured to it"), but on occasions, I suggest, it happens because he lifts the knife, then fails to plunge it in. When he observes that economic relations as they are currently played out threaten people's sense of what life is and what reality means, surely what he's really saying is that capitalism damages people. To my surprise, he agrees. Does he therefore think economic relations should be ordered in a different way? "Yes." So is it fair to say, then, that he's anti-free market capitalism? "Yes," he says and roars with laughter. "Don't you feel better for my having said it?"

He goes on to rehearse what he insists he's said before ("I don't mind saying it again") about how no one can any longer regard the free market as a naturally beneficent mechanism, and how more sophisticated financial instruments have made it even harder to spot when the market's causing real hurt. But he sounds more passionate when he relates his theories to his recent experiences in Africa. "I came back yesterday morning from the Congo. What I've been looking at there and in Kenya is localism of a certain kind. The church is doing really remarkable things with new farming techniques, in a cluster of villages. Things like a biogas project to prevent the cutting down of trees for fuel – very low-investment, very low-technology solutions. I think one of the most moving experiences – yes, moving – was at a village in Kenya that had, thanks to the work of the local church, rethought its farming practices, restocked with indigenous plants, begun to explore very tentatively local fisheries and, out of the modest profits, was just about to start credit union arrangements for the whole community. Now that's localism, if you like."

I can't help responding to his enthusiasm by noticing that he seems to be one of those people who always sounds refreshed when talking about the micro-picture and depressed when contemplating the macro. "There's a lot in that." In Congo, he says, he has been especially impressed by his meetings with youngsters who have been abducted and brutalised, and women who've been raped. He had realised there was nobody but the church to hang on to these people. "Especially the youngsters who'd been in the militias. They talked about how the church hadn't given up on them. Their own communities wouldn't receive them back because of where they'd been and what they'd done. But the church tried to keep the door open."

Inevitably Williams joshes me when I say how struck I have been by the depth of his belief in the church ("Headline: Archbishop believes in church"), but I assure him I am not being facetious. In fact, I've wondered whether the attitude he displays in his writings – "We can trust the church because it is the sort of community it is... I have seen the church and it works" – has left him obsessively frightened of schism. Is he paying too high a price for keeping together people who believe different things about gender, priesthood and sexuality? "I've no sympathy for that view. I don't want to see the church so balkanised that we talk only to people we like and agree with. Thirty years ago, little knowing what fate had in store, I wrote an article about the role of a bishop, saying a bishop is a person who has to make each side of a debate audible to the other. The words 'irony' and 'prescience' come to mind. And of course you attract the reproach that you lack the courage of leadership and so on. But to me it's a question of what only the archbishop of Canterbury can do."

It's striking that throughout his eight years in charge, Williams has been touring as God's fairground boxer, willing to go five rounds with all comers. Up steps AC Grayling, next day Philip Pullman. But his fondness for quoting Saint Ambrose – "It does not suit God to save his people by arguments" – suggests how little store he sets by such encounters. "Oh, look, argument has the role of damage limitation. The number of people who acquire faith by argument is actually rather small. But if people are saying stupid things about the Christian faith, then it helps just to say, 'Come on, that won't work.' There is a miasma of assumptions: first, that you can't have a scientific worldview and a religious faith; second, that there is an insoluble problem about God and suffering in the world; and third, that all Christians are neurotic about sex. But the arguments have been recycled and refought more times than we've had hot dinners, and I do groan in spirit when I pick up another book about why you shouldn't believe in God. Oh dear! Bertrand Russell in 1923! And while I think it's necessary to go on rather wearily putting down markers saying, 'No, that's not what Christian theology says' and, 'No, that argument doesn't make sense', that's the background noise. What changes people is the extraordinary sense that things come together. Is it Eliot or Yeats who talks about a poem coming together with an audible click? You think, yes, the world makes sense looked at like that."

I ask if that's the criterion – that the world should make sense. "Make sense not in a great theoretical system, but that you can see the connections somehow and – I tend to reach for musical analogies here – you can hear the harmonics. You may not have everything tied up in every detail, but there's enough of that harmonic available to think, 'OK, I can risk aligning myself with this.' Because you're never going to nail it to the floor and eat your heart out, Richard Dawkins!

"You know that scene in the Woody Allen film where they have an argument in a cinema queue, and Marshall McLuhan is standing behind them and able to interrupt to settle the argument? Woody Allen turns to the camera and says, 'Wouldn't it be wonderful if life were like that?' Well, no Marshall McLuhan will ever step forward in the queue and say to Richard Dawkins, 'The archbishop's right.' It's not going to happen."

Williams speaks so gingerly about human beings, always unwilling to impute motive, that it's shocking when you move on to theology and realise how uncompromising his version of God is. He rarely uses the word "faith". He prefers the word "trust" because, he says, "it sounds less like product placement". In print, he goes out of his way to emphasise that God doesn't need us. "We must get to grips with the idea that we don't contribute anything to God, that God would be the same God if we had never been created. God is simply and eternally happy to be God." How on Earth can he possibly know such a thing? "My reason for saying that is to push back on what I see as a kind of sentimentality in theology. Our relationship with God is in many ways like an intimate human relationship, but it's also deeply unlike. In no sense do I exist to solve God's problems or to make God feel better." In other words, I say, you hate the psychiatrist/patient therapy model that so many people adopt when thinking of God? "Exactly. I know it's counterintuitive, but it's what the classical understanding of God is about. God's act in creating the world is gratuitous, so everything comes to me as a gift. God simply wills that there shall be joy for something other than himself. That is the lifeblood of what I believe."

I say that's all very well, but how then can he be so critical of self-absorption when he himself is a poet? Surely self-study is necessary to create art? "Ah, yes, two very different things. Self-absorption means thinking the most interesting thing in the world is myself. Self-scrutiny, on the other hand, is very deeply part of the Christian experience." So is his religion a relief, a way of escaping self? "Yes. We are able to lay down the heavy burden of self-justification. Put it this way, if I'm not absolutely paralysed by the question, 'Am I right? Am I safe?' then there are more things I can ask of myself. I can afford to be wrong. In my middle 20s, I was an angst-ridden young man, with a lot of worries about whether I was doing enough suffering and whether I was compassionate enough. But the late, great Mother Mary Clare said to me, 'You don't have to suffer for the sins of the world, darling. It's been done.'"

As we both relish this, my time as his guest is nearly up, but not before I toss out a succession of quick questions, designed to throw him off balance... If you could change one thing about British society, what would it be? "A more realistic prison policy." If you could change one thing about the church? "Rethink the General Synod." What music will you have at your funeral? "Bach and a bit of Dowland." In 2007 you called people who want to attack Iran or Syria criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous. Do you still feel that? "Yes." Libya? "Protect civilians, fine, stand up for reconstruction. But look at the experience of the last 10 years." But even as he screws up his eyes in response to my bullying, I can tell he's longing to return to the subject of poetry and to give me a book of his own.

Earlier in the conversation, Williams has attributed to Auden a quotation about poems never being finished, only abandoned. For the pleasure of forever being able to boast that I've gambled with the archbishop of Canterbury, I have tried to bet him £5 that it's Eliot. (Research later reveals we're both wrong. It's Valéry. Money to charity, of course.) So as he signs a dedication, I ask him if he's happy to be thought of in a tradition of Welsh poet-priests – George Herbert, Gerard Manley Hopkins, RS Thomas? "I always get annoyed when people call RS Thomas a poet-priest. He's a poet, dammit. And a very good one. The implication is that somehow a poet-priest can get away with things a real poet can't, or a real priest can't. I'm very huffy about that. But I do accept there's something in the pastoral office that does express itself appropriately in poetry. And the curious kind of invitation to the most vulnerable places in people that is part of priesthood does come up somewhere in poetic terms.

"Herbert's very important to me. Herbert's the man. Partly because of the absolute candour when he says, I'm going to let rip, I'm feeling I can't stand God, I've had more than enough of Him. OK, let it run, get it out there. And then, just as the vehicle is careering towards the cliff edge, there's a squeal of brakes. 'Methought I heard one calling Child!/And I replied My Lord.' I love that ending, because it means, 'Sorry, yes, OK, I'm not feeling any happier, but there's nowhere else to go.' Herbert is not sweet."

"And you like that?"

"Non-sweetness? I do."