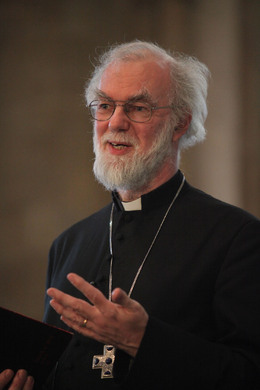

Archbishop of Canterbury’s Presidential Address

Saturday 9th July 2011

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, delivered his Presidential Address today at the General Synod's July 2011 Group of Sessions, held at York University.The full text is below, or listen to the speech by clicking the download on the right.

Two weeks ago in Eastern Congo, listening to the experiences of young men and women who had been forced into service with the militias in the civil wars, forced therefore into atrocities done and suffered that don’t bear thinking about, I discovered all over again why the Church mattered. One after another, they kept saying, ‘The Church didn’t abandon us.’ Members of the Church went into the forests to look for them, risked their lives in making contacts, risked their reputations by bringing them back and working to reintegrate them into local communities.

And I thought, listening to them, ‘If it wasn’t for the Church, no-one, absolutely no-one, would have cared, and they would be lost still.’ It was almost a fierce sense, almost an angry feeling, this knowledge that the Church mattered so intensely. It put into perspective the fashionable sneers that the Church here lives with, the various excuses people make for not taking seriously the idea that God’s incalculable love for every person is the only solid foundation for a human dignity that is beyond question. And it put into a harsh light the self-indulgence of so much of our church life which provides people with just the excuses they need for not taking God seriously. It left me wanting to be a Christian. It left me thinking that there is nothing on earth so transforming as a Church in love.

Congo isn’t unique. I’d just had a week in Kenya, where I saw ample evidence of how the Church stays at the forefront both of national reconciliation and of practical regeneration, and how its teaching programmes blend seamlessly together the new and grateful confidence that the gospel brings with the prosaic business of releasing skills and assets in a community so that food security is improved, soil replenished by better, simpler and more responsible farming techniques, co-operative schemes established and so on – always with the Scripture-reading congregation at the centre, learning what the new humanity means in practice, always with an unquestioning hospitality to the entire community. No, Congo isn’t unique. And today especially we will have particularly in our hearts another of our sister churches that has once again been the carrier of hope and endurance for a whole people in times of terrible suffering, as the new republic of Southern Sudan begins its independent life. But what is special in places like Congo and Sudan is a Church with negligible administrative structures and no historic resources working with such prolific energy. ‘Silver and gold have I none…’ But what they have is, somehow, the strength not to abandon, not to stigmatise, not to reject, but always to seek to rebuild even the most devastated lives. What they have is the strength not to abandon. I wish I had the words to express more clearly to you what that strength looks and feels like, but I can only give thanks for seeing it.

Last year, we identified priorities for the coming five years – growth in numbers and spiritual maturity; service with the best and most focused use of our resources; a renewed ministry. And today we’ve taken the risk of giving ourselves time and space to share our thoughts on what that might mean. What I want to do is to frame those thoughts within the context of this vision of a Church in love as I was privileged to meet it in Congo and Kenya, and to prompt the question of what would be lost in this context or that if the Church of England were not here. Perhaps only as we think about what would be lost do we really get a purchase on what matters most.

We want to see growth, spiritually and numerically. In this connection, spiritual growth must mean growth in the strength I have mentioned – that is, growth in awareness of what it means that God does not abandon us, out of which grows the conviction that we have the resource not to abandon one another or to abandon the setting in which we are placed. Growth, I want to say, is growth in the power to show God’s fidelity – always, by definition, a power unthinkable without the prior act and prompting of the Spirit. To grow in this sense is to become daily more conscious of the words with which the Great Commission of Mt 28 ends – ‘I am with you always.’ Without this, carrying out the Great Commission becomes a programme of human expansion and recruitment only. Begin with this awareness – and it can be a terrifying as well as a consoling awareness – and our own mission is reconfigured as bound up with the same costly ‘walking with’ the human world that Jesus has undertaken in life and death.

And our appeal in mission therefore has to be, ‘Walk with us as we walk with Jesus.’ Walk and continue learning – there is no entrance test except the willingness to trust that walking with Jesus is the way to life and reality. Unless we look purposive in this respect, we shall simply be asking people to accept another ideology, to sign up to another programme. Back to Congo: it is only when believers are passionate about the God who has not abandoned them that others will see faith as the gift of transformed relation with the world (as well as with God) – and so may see that their lives may genuinely become different if they walk with Christ.

The American Presbyterian writer Timothy Keller has recently published a book on Mark’s gospel, entitled King’s Cross. It is a vividly written and often very moving presentation of the great themes of the gospel (and incidentally offers a forceful defence of substitutionary language for the atonement that might give second thoughts to some who find this difficult); but perhaps its simplest and most dominant insight is that Christianity is not advice but news. The world has changed; humanity is not what it was. We are still working out, often in floundering and stumbling ways, what this means, but the one thing to beware of is reducing the news to exhortation, sound moral or even spiritual teaching, alone. We must always be beginning again with the news that God has shown himself to be a God who does not abandon – even when all the evidence has pointed to his absence, he recovers himself and us in the great act of vindication, homecoming and transfiguration that is the resurrection; a moment so alarmingly beyond all expectation that Mark can only present it with the silence, the fear and trembling, of his famous ending at 16.8. And I suppose that what I am pleading for in our discussion today is a revitalised sense of the news we have, the event we celebrate as having changed everything.

When you discuss all this, perhaps the question to ask is first, ‘What does it mean to each of us that God does not abandon us?’ How have we learned this? And what are the habits we have developed to keep this sense alive in us? Arising from this, with Congo in our minds, can we then go on to ask, ‘Where do we see the Church we know locally acting in this way, acting as the sign and presence of the God who does not abandon?’ This may help us focus on the issue I hinted at earlier, the question of what would not happen if the Church were not here.

The main point is really to make the connection between growth and service. To grow in awareness of how God has not deserted us is inseparable from living a life in which we do not abandon those whom God calls us to be faithful to – inside and outside the Church. And the witness of people who have the strength not to abandon becomes itself a powerful appeal, an invitation to new reality and new potential. God reconciled us to himself, says St Paul, and he gave us the strength to serve the work of reconciliation. This is, in Paul’s terms, the substance of the appeal we make, the ‘embassy’ we undertake on God’s behalf – and it is also the heart of the newness of the new creation (II Cor.5.17-20). A new creation is, we might suppose, a newness that touches everything; and this can only be shown where it is clear that God’s love touches everything and does not ignore or desert any created being. If we recognise that God in Christ has touched even the inmost dimensions of our complicated and compromised being, we can bear witness to God’s freedom to be there in every corner of what is made, to be faithful to his original creating word.

News not advice. News that can be communicated only by being acted out in our own efforts at faithfulness. So that when we ask about the use of our resources, the first issue we should be considering is surely how we keep faith with the society in which we are placed, how we show ourselves trustworthy in rapidly developing circumstances. It isn’t an easy matter, because keeping faith is not the same as never changing; as has been said – by Cardinal Newman among others – in a changing world we have to change to stay the same. This doesn’t mean we have to change in the same way that the world is changing, which is an all too tempting misunderstanding, but that we have to work at finding today words and acts that have the same challenging and transforming effect that older words and actions had. You may be reminded of Bonhoeffer’s great letter to his godson in May 1944, struggling to imagine the kind of new language for faith that would have the same revolutionary and liberating force that the very words of Jesus had. We keep faith with our society by searching all the time for the words and acts that keep faith today with the essence of Jesus’ challenge to the culture, the religion and the righteousness of his day. And this means a difficult and constantly renewed discernment.

So with our involvement in, for example, education, we are faced at the moment with a startlingly far-reaching prospect of restructuring. Putting aside for the moment the matter of admissions policies – a good example of how reporting can manufacture a drama out of little more than a restatement of what is already being done – the deeper question is something like this. How, in the context of far-reaching changes to how education is delivered in this country, do we continue to offer what we have always offered? Which is not a system of confessional schools designed to secure our membership, but a critical partnership with the state that seeks to keep open for as many children as possible the fullest range imaginable of educational enrichment – assuming, as we do, that such enrichment involves an honest and thoughtful exposure to the Christian faith. Furthermore, our history as educators in this country – and it’s a theme well worth underlining in this anniversary year of the National Society – is much to do with offering possibilities in social contexts where other providers have practically given up or have settled for less than the best. In recent years, our record with the opening of new academies has been fully in this tradition. As academies change from being a strategy to help the most disadvantaged to being something like the norm, as part of a more ‘choice’-driven system, we have a considerable agenda to work at if we want to stay faithful to that tradition.

One example among many possible ones, but probably one of the most immediate; it focuses the question of what it now means to do the same, to show the same commitment to those who are most likely to feel abandoned or betrayed by the systems of their society. In a similar way, we are currently looking at how the Church Urban Fund continues to operate effectively in a new environment with new challenges. As we come to terms with the agenda of localism, we have to ask as a Church what radical new resourcing of community work is going to be needed in a time of austerity, with heavy new expectations laid on voluntary provision. The question here that you might want to look at is about how we start imagining the new enterprises, policies and structures that will embody faithfulness both to God’s imperatives and to those around us. Synod does not settle the details of resource allocation – but it has a crucial part to play in settling the framework in which such allocations are made. Start by thinking about the local setting, the schools and community projects you know about, and think about what the prognosis for them looks like in the next two to three years.

And mention of resources is bound to raise the issue of ministry, if only because that is where a huge amount of our financial resource quite rightly goes – and also because the presence or otherwise of effective ministry (ordained and otherwise) is felt as one of the most immediate touchstones of whether or not people feel abandoned. Effective ministerial presence is essential if people are to be in touch with the faithfulness of God through the Church. It is more than just the presence of the worshipping community, vital as that is: this community has to have its presence focused and personalised in a way that makes it accessible. And that is a central aspect of the role of the ordained, both directly (as the identifiable face of the worshipping community) and indirectly, as the catalyst that prompts worshippers into service by the repetition of the news of the gospel.

In the light of all that I’ve said so far, we can see, I hope, that an effective ordained ministry in the coming generation is one that is shaped by the determination to keep faith: one that is rooted in what I have already been talking about, the conviction that God does not abandon you as a person, one that is focused on communicating to people the fact that God and God’s Church are to be trusted not to desert them. This puts the issue of formation at the heart of things, because both of these dimensions of ordained ministry require a certain kind of character. The habits have to be developed of reflecting on the single all-embracing story of God’s dealings with us in connection with daily self-questioning and daily thanksgiving – so as to understand more and more how God’s faithfulness in an individual life is a ‘replaying’ of the faithfulness shown in the great story of salvation.

Biblical awareness and self-awareness go together; and both need a steady attention to the tradition, in the sense of the whole deposit of what has been prayed and understood in and by the Body of Christ across the ages. Both also need attention to one’s own way of being in the world. Ministering in such a way that what comes through is God’s refusal to abandon the world requires personal habits and qualities – the refusal of hasty solutions, a suspicion of politicised or polarised religiosity, a sense of proportion, a wariness of easy definitions of success, a real willingness to allow others the right to make their own mistakes and a keen sense of your own capacity for mistake and hurt. It might be a good idea to share some experiences of ordained ministers we’ve known who have lived this out, and then to ask how our training institutions nourish such a character, and what patterns of collaboration and deployment will best serve this vision. We are never likely to return to the mythological past beloved of some critics when every small parish had its resident full-time pastor. But – to pick up ideas and experiments that are being explored at the moment – sometimes what matters is having a person (literally a ‘parson’) in each small community who is genuinely recognisable as the focus of the Church’s presence, ordained or not; so that the ordained minister is there as friend and support for a number of such ‘presences’, and trained to recognise their giftings. But this is not just a matter of encouraging people to ‘do jobs’ for the Church. It is also about the way an ordained person can keep alive and impart to others ways of giving thanks, drawing together the prayer and aspiration of a community. So how far do we currently think about an ordained minister as someone who can as a real priority communicate what the worship of the Church really is and help others to animate it?

The ordained minister as co-ordinator, as liturgist and trainer in liturgy, as well as teacher and inspirer in the more usual ways, the ordained person as celebrant of the community in a very full sense, and one who helps others learn how to celebrate in the name of the Church – this is surely one dimension of where we are being led today, and it poses searching questions to our training processes. Have we yielded too much to the pressures of university accreditation (a quite different issue from the need for theological excellence and intellectual edge)? How do we as a church reclaim some of our own authority in this area without becoming caught in a narrow ‘seminary’ culture (a danger for all varieties of churchmanship, it has to be said)? Can we create a style of ministerial training that enables the ordained minister to be above all someone who knows how to bring together the voice of the universal Church, reading the Bible and remembering the witness of the centuries and the voice of this or that local community? This becomes possible when there is a real fusion between awareness of the tradition and deep empathetic listening to what is being said and felt now – a fusion that is at the centre of any ordained identity, I believe.

I’ve stressed this celebratory aspect of ordained ministry – and the need for the ordained person to be able to assist others to pray and give thanks in the voice and spirit of the Church universal – because the centrality of thanksgiving and celebration is the way in which we are reminded of the priority of news over advice in the Church. This is how we discover the unique treasure of the Church, its strength to be present and not to abandon, given to it in Christ’s Spirit. ‘Silver and gold have I none…’ What we offer is God’s commitment, embodied imperfectly in our own determination to be faithfully committed; offered in the confident hope that it is commitment that creates commitment in others – as God’s own faithfulness draws out our efforts to be faithful. Growth, service and renewed ministry all depend on the constant return to and celebration of God’s promise and his performance of his promise.

This morning is a rare opportunity for members of Synod to talk with each other about what it has felt like for them to be Christians, and to exchange their perceptions of what it is that would for ever be lost if the Church were not here. To repeat yet again a theme I’ve touched on in a good many Synod addresses, we have a chance of discovering what it is for Synod to behave as a cell in the Body of Christ, as a kind of church. We spend a fair amount of time expressing what we want changed in the Church, what frustrates or disillusions us. But I hope that today we can do something different and celebrate a Church that deserves our loyalty – not because it is humanly impressive and successful but simply because it is Church, because it is the visible sign of a faithful God. Make the most of it. It may be that reflecting on this will help us love the Church in the way we should; when we love the Church for what it actually is in the eyes of God, we have a better chance of becoming what I called earlier a Church in love. And only a Church in love can really convert, serve and celebrate. Pray that our work today will bring into focus in new ways what it means to be entrusted with the strength not to abandon and the joy of knowing ourselves not abandoned.

In Thine own service make us glad and free,

And grant us nevermore to part with Thee.

© Rowan Williams 2011