Into the Heart of Africa - Church Times article

Friday 1st July 2011

Earlier this week, the Archbishop of Canterbury made a pastoral visit to the Church in north-east Congo, which is rebuilding after conflict. Malcolm Doney went with him.When the Archbishop of Canterbury clambered out of the tiny Cessna 260 on the runway at Bunia airport, the Mothers' Union choir launched into song, scores of children waved, and a panoply of Congolese bishops shuffled into line. For the second time.

Minutes before, a grander aircraft had touched down, and everyone had assumed that Dr Williams was on that.

If there is an aeronautical equivalent to entering on a donkey, the Mission Aviation Fellowship single-prop plane would be it. Despite its impromptu rehearsal, the reception party was enthusiastic. Everyone was proud that L'Archevêque de Canterbury et Père Spirituel de la Communion Anglicane Mondiale was here.

Dr Williams travels in a grey clerical shirt and a black suit — well, a black jacket and trousers that nearly match. This is part-artlessness and part-design, dating back to when he was first made Bishop of Monmouth: "I felt it was probably a bit more important to be identifiably alongside the clergy, than underlining the difference," he said. "And I feel a bit of a fraud looking too much like a sort of imperial legate."

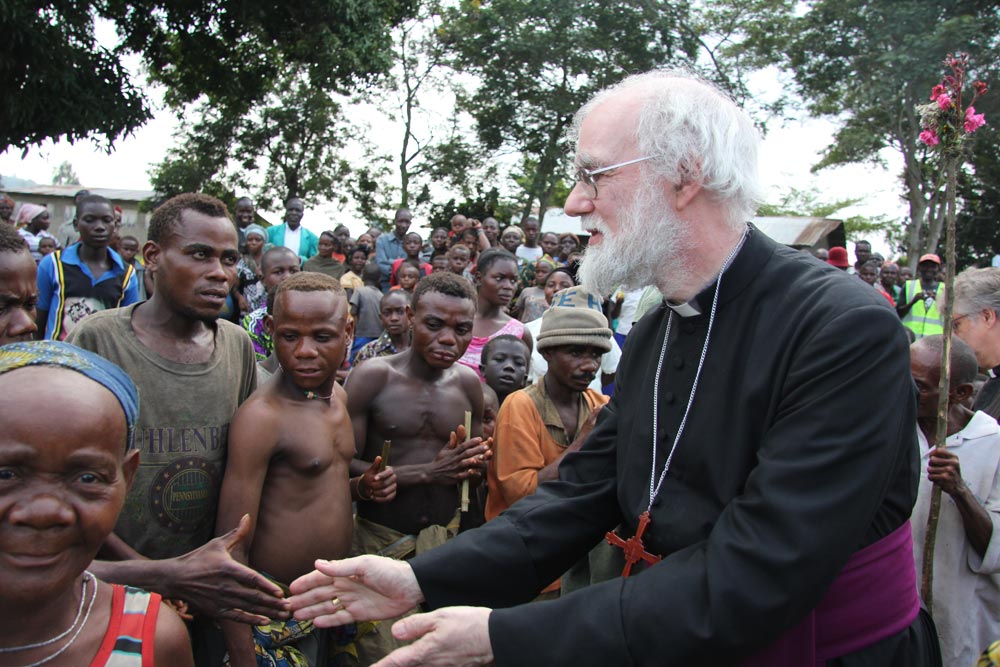

Consequently, he did not throw himself into the dancing, or give high fives to the children. But he waved, shook hands, and beamed widely. The welcome, he consoled himself, was not for Rowan Williams: "it's for a global symbol of the global Christian family, visiting its members." But the warm embrace he received from the new Primate of the Province of Congo, the Most Revd Henri Isingoma, told another story.

Certainly, the Anglican Church here was delighted with the spotlight Dr Williams's visit shone on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), not least because the British ambassador, Neil Wigan, had flown more than 1000 miles from the capital, Kinshasa, to be here for the duration of the visit.

"It's hugely significant for people here to have someone who's a global figure to come and engage with things," Mr Wigan said.

"This is a historical occasion," said Archbishop Isingoma. "He is the first Archbishop of Canterbury to come here since Robert Runcie in 1981."

His wife, Mugisa, concurred. "This visit puts us on the map. As a result of this, the Anglican Church has a voice."

This was last Friday morning. After an impromptu press conference (in French), a cavalcade, including an armed detachment, headed for Bunia's sports stadium. Here, the singing and dancing continued, until the late and theatrical entrance of the Governor of Orientale. He strode into the arena sporting a broad-brimmed leather stetson, and followed by a retinue of supporters. He told the crowd that the President of Congo, Joseph Kabila, had told him to drop everything to fly here to greet the Archbishop.

It was beginning to feel more like a state visit than the pastoral occasion that Lambeth Palace had described it as. But, as the Archbishop's embrace had presaged, it became clear that affection for Dr Williams the man matches the respect for his office. "The problems we have are in your heart," said Archbishop Isingoma, in his welcoming remarks. "You comfort us in our difficulties."

It is because of these difficulties that Dr Williams is here. He came direct to Congo from Kenya, which has had its share of incendiary violence. "What prompted me to want to come was meeting the Congolese bishops last year at Entebbe. Things were quite critical in the country then, and I felt I needed to go and see, and offer some kind of solidarity."

The recent history of violence in the DRC is legendary. "There is a legacy of 30 years of a both brutal and incompetent dictatorship, followed by one of the worst civil wars in post colonial Africa," Mr Wigan said. Almost every participating force has been guilty of massacres and rapes. And the north-east region that we are visiting was described by Human Rights Watch as "the bloodiest corner of Congo".

Here, a bitter conflict was fought mostly between the Hema and the Lendu tribes. Small local militias were armed and directed by manipulating forces, including neighbouring nations such as Uganda and Rwanda, Human Rights Watch says. In and around Bunia, Hema and Lendu lived cheek by jowl and often worshipped together in the same church. They were dangerous times.

Henri Isingoma and his wife were both born in the region, moving away before the war to Katanga, when he was made Bishop. On his return to the diocese of Boga in 2007, even though the war was on the wane, he was distressed at the enmity between the Hema and Lendu.

The main road that linked Bunia to Boga was closed, even to the UN, because it was still dangerous. No one could visit scattered members of their family, and congregations were riven.

One night, against all advice, Bishop Insingoma recruited 30 clergy of mixed tribes to drive down the road to meet Lendu people in their refugee camp. The night before the trip, the fighting grew fierce. The clergy began to cry off, leaving him with a half-empty bus. For the first 25 miles, people were chatting and joking, but, as they drew nearer to Lendu territory, the bus grew strangely quiet.

They reached a camp that held 4000 refugees, and were met with huge enthusiasm. "Many of these people hadn't seen one another for five years." This brave action proved to be a pivotal moment. "After that, we took the bus again and again along the road, and, in the end, the UN agreed to open the road once more."

Such an action was only the start, however. Once these initial contacts were made, the Bishop initiated a programme where the long, slow process of healing could take place. At its core was a practice, perhaps surprising for this essentially Evangelical Church: confession. Through a process of allowing people to share stories of what had taken place during the war, and to eat, pray, and sing together, Bishop Isingoma encouraged individuals to own up to what they had done: killing, rape, assault, theft . . . and to ask for forgiveness.

Confession was also the theme of a remarkable youth presentation that took place on Friday evening in the function room of a hotel. Agape Mahagi is a youth organisation, founded by a remarkable Englishwoman, Judy Acheson. She first came to Congo in 1980 as a nur-sery nurse, but, as her charges grew, she carried on caring for them, eventually training and handing over responsibility to local leaders.

The civil war was a testing time for Agape. Vicious militia raids took place, and many of its young people saw their parents and siblings murdered or raped, and their homes destroyed. Many boys and young men, often still schoolchildren, joined their own tribal militias, either to exact revenge, or because they believed that this was the best way to protect their families and communities.

Agape's director at the time was the Revd William Bahemuka, known affectionately as Willie, who has just been installed as Bishop of Boga, after Henri Isingoma's translation as Archbishop. He, together with other youth leaders and congregation members, were determined not to lose their young people, despite the horrific acts their militia leaders encouraged them to commit.

"People in local villages and communities knew who had left to join the militias," Bishop Bahemuka recalls; "so, when they visited home for food or to see their families, we would make contact, and tried to persuade them to leave." Brave individuals would even follow them into the militia camps, and continue entreating them.

The fruit of this determination was evident last week. A group of about 50 former militia members spoke about how the Church, in the form of Agape, never forgot them. It was hard to imagine these gentle youths as people who may have killed, mutilated, and raped in the past. One by one, they gave their testimony. "We were taught to repay bad for bad," one said, "but the people from the church came to visit me."

One after another they spoke about how, thanks to Agape's surprisingly formal seminars and conferences on peace, they retuned to God and their families, rediscovering the love of Jesus. Many of them were now at college or university, slowly putting their trauma behind them.

Dr Williams was moved. "They were there, talking in a room which included the victims of such activity — able to talk about it because the Church had held on to them. I felt this is so completely what the Church is for.

"Again and again in my visit to Kenya, but much more in Congo, I kept saying to myself: Who else can do this? I thought of Cardinal Newman's remark, that if the Church didn't exist, the world wouldn't last much longer.

"The only reason people have for hanging on to the offenders, hanging on to the victims, hanging on to the different tribes, and labouring away to build something, the only reason they have is because they take the gospel seriously. If they didn't, these people would be far more vulnerable."

The following day, Saturday, the Archbishop laid a foundation stone at a new Mothers' Union centre for women's counselling in Bunia. As a sign of the underlying tensions in the area, even this activity was done under the vigilant eye of "Monsieur Gerry", a Belgian giant lent by the UN as Dr Williams's personal minder.

That afternoon, we flew to Boga, to the Anglican cathedral named after Apolo Kivebulaya, the Ugandan missionary and adopted saint, who, in 1896, founded the Anglican Church in Congo here. He arrived carrying a Bible and a hoe, so that he could preach the gospel and also feed himself.

The Archbishop's schedule was packed and often ran late. The "set pieces" were two large services to preach at, a university to open, a bishops' retreat to close, a chief to visit, and two celebratory lunches at which he was guest of honour.

Sandwiched between the weekend's set pieces are moments of interchange that he values enormously: "I know that the human contacts are going to be slight and transitory. But I'd be very unhappy indeed about a visit that didn't include some of that face-to-face encounter. That's actually what touches and enlarges you, and that's where the gift comes to you as a visitor."

In Boga, he has a fleeting visit with a group of about 50 pygmies, who now purposely call themselves "citizens", because they have for so long been regarded as outcasts. About 500 of them are camped in this region, displaced from their normal forest homeland by the conflict. "We just want to go home," their leader pleads. The appeal is noted.

More significantly, in a discreet corner of the cathedral compound, Dr Williams meets a group of women who have been victims of violent sexual attack.

The use of rape as a weapon of war has been a notorious feature of the conflict in the DRC. A paper published in the American Journal of Public Health estimates that, in one 12-month period at the height of the war, 1150 women were raped every day.

There were immediate consequences of such violence: unwanted pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV and AIDs; but the victims have also suffered isolation and stigma. Those who have been raped are, more often than not, shunned by their families, left without the ability to earn a living.

"It was very important to listen directly to some of the stories," Dr Williams said afterwards. "It was a very private event, simply an opportunity for them to talk in a safe environment about what they'd experienced."

Just like the Agape project among the youth in Bunia, the Church here has responded actively to this trauma. Mrs Isingoma took a lead.

In concert with the Mothers' Union, itself a potent force in Congo, Mrs Isingoma established the Women's Union for the Advancement of Peace in Society (UFPPS). The aim is to give back to these women the "éspoir de vivre" — their hope for life. This national organisation is very active in the diocese of Boga, where they are establishing a clinic, counselling programmes, and training facilities, so that women can develop marketable skills.

Alongside this, a couples' ministry has been established, aimed particularly at the husbands, to restore the bond that had been brutally shattered. "There is a need for the love of Christ to be demonstrated in the healing of these marriages," Mrs Isingoma said.

Dr Williams was struck by the bravery and tenacity of the women. "Listening to someone who had an unspeakable history of abuse, multiple assault, and the murder of most of her family, talking about her university studies. . . That's miraculous, in a way."

Later, in a private meeting with the head of the UN local office of the UN Mission in Congo, the Archbishop is able to outline the work that the Church is undertaking through Agape and UFPPS, and to pass on the plea from the citizens. Dr Williams's standing as a global statesman had obvious value: he was able to act as an advocate for the Church's work, some of which seemed not yet to have appeared on the UN's radar. As Mrs Isingoma had predicted, the voice of the Anglican Church was now made clear.

The Church in Congo told Lambeth Palace before the visit that it was tired of the media image of a country riddled with conflict, rape, and corruption. Within the first five minutes of our arrival, both Archbishop Isingoma and Bishop Bahemuka had told me of their desire that we see Congo as a nation under reconstruction.

Driving through the streets of Bunia with Archdeacon Bezalari Kahigwa — who, as parish priest, had played a significant part in holding on to those young people tempted to join the militia — he remarked on the amount of building that was taking place. "During the war, nobody built anything," he said. "All people could think of was survival. Now they are beginning to look further ahead."

Sitting in Entebbe airport, in Uganda, a couple of hours after an emotional goodbye at Bunia, Dr Williams reflected on this ambition.

"People endure, and do something more than endure: they imagine. That's the key thing: 'I could be different, things could be different. I could be different because people around me help make that true.'

"I never know quite what to say when people ask, am I feeling optimistic? The glib answer, which I've made more than once, is that I'm not optimistic: I'm hopeful. . . But in all seriousness, it's not so much a matter of optimism or pessimism: it's a matter of are there things which are worth investing energy and support in? In Congo, with, for instance, the work among women, the answer is manifestly yes.

"Clearly, you can say that it's a very volatile situation. Just this morning, news came through of another mass rape in South Kivu. Every little advance seems to be paid for with another explosion of misery. But the worst possible response, the most unchristian response, is to say: 'Well, it's all going to hell in a handcart.'

"The Church is a community that transcends tribal and local identities. It doesn't give up on people, whatever the circumstances. The Church is not going to go away."

Earlier that morning, Archbishop Isingoma had said in farewell: "We have a saying: 'The true friend is the one we see in moments of distress.' For the Congolese people, you are a friend because of the pastoral care you have ministered to us as a spiritual father."

Such an accolade might belong formally to the office of Archbishop of Canterbury, but it also belongs to Rowan Williams.