Relations between the Church and state today: what is the role of the Christian citizen?

Tuesday 1st March 2011

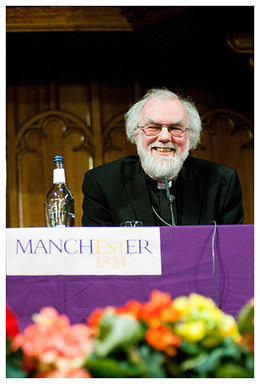

An address given by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, at Manchester University, 1 March 2011, during a joint visit to the city of Manchester with the Archbishop of York.The full text of the address is below:

In reflecting on Church and state, I want not simply to talk about two kinds of institution, but about one particular area of political and religious thought where I believe very strongly the concerns of Church and state overlap, and overlap creatively; which is why the subtitle of my lecture tonight is about how the Church contributes to the identity we call the identity of a citizen. And I begin with the simple question: how do we define a citizen? To do this, it may help to go back in history a little bit and to think about the context in which the language of citizenship first appeared in the ancient world, in Greece and Rome.

What you could say in a nutshell is that the definition of a citizen is somebody who is not a slave. A citizen is someone whose choices and destiny are not owned by someone else. And a citizen therefore is someone who has a voice in the community, who is protected as an individual by the law and who can in some significant degree decide the circumstances of their personal life. A slave is someone who enjoys none of those privileges. A slave is someone who does not have a voice in public decision-making, who does not have protection by law, whose circumstances are decided by someone else. So to be a citizen is to have both a public and a private dignity – the public dignity of being a decision-maker, someone whose voice is guaranteed a hearing, and the private or personal dignity of contributing what you have to a common project, a public project, a vision or purpose shared in the community. To be a citizen is to be responsible for maintaining your environment, your personal and social environment.

A voice guaranteed a hearing and a person protected by law: even in the Roman Empire—which was certainly not a model of democratic government—that reality had some residual force. And of course one of the most powerful examples of that is the stories we encounter in the book of the Acts of the Apostles in Christian scripture, where St Paul is able more than once to surprise and alarm soldiers and administrators who are ready to bully or torture him, by reminding them that he is actually a Roman Citizen and that therefore there are certain things that they cannot do to him. When he is summarily thrown into prison in Philippi and released by an earthquake, in one of the more dramatic episodes of his career, he demands an apology from the civic authorities the next day because they have failed to treat him as a citizen.

Now that example from Acts is not just an interesting anecdote, because if we look at Christian scripture and early Christian literature in general we find that the image and the idea of being a citizen play a very important role indeed in the self-identity of early Christians. To be a member of the early Christian church was to be a certain kind of citizen. The ekklesia—the Greek work which we translate as ‘church’—was, in the usage of the ancient world, the name you gave to the assembly of citizens. So if you joined the church you were joining a body whose main metaphor for what it was about was a metaphor drawn from civic and political life. You were a citizen – not of the Roman Empire perhaps (you might or might not be), but you were a citizen of somewhere, of something. You belonged to what St Paul in one of his letters calls a politeia, a political unit and your citizenship was given from God in that political unit, the new community of the new creation. Early Christianity thus from the start said that, whatever may be the case in the political arrangements around you, there is another polis, another city, another political unit, in which, whatever your status in this world, you have non-negotiable rights and dignities. There is a human community, never mind the political arrangements around you, in which you have a voice, a gift to share; in which you have the dignity of being a decision maker and a capacity to build and sustain the environment in which you find yourself.

The Christian Church presents itself in its very origins as a political body, a polis, a kind of city. And its members therefore are citizens before anything else. To belong in the body of Christ, to use the other great metaphor in the New Testament, is to have the dignities of a citizen. Civic liberty, civic dignity is one of the favoured ways of expressing what it is to come into the community established by Jesus Christ. Which is why, from the beginning, the Christian community looked like, and in many ways was a counter-culture. It was what some sociologists and historians call an imagined community (which is of course not the same as an imaginary community, like having an imaginary friend): an imagined community – the community of the human imagination, which allows you to ‘image’ and imagine yourself in a particular way, with consequences for the other communities that you are part of. In principle, to belong to the Christian community is to learn civic virtues that will create civic flourishing, and to learn how to exercise those tasks of decision-making within community and maintaining and sustaining a human environment.

I underline this because I believe it’s very important to recognise that early Christianity is not an opting-out of politics but a living-out of another kind of political identity and vision. It’s not removing people from civic responsibility; it is saying you learn the deepest kind of civic responsibility and civic virtue in this community. And at times in the ancient world the civic identity, the political identity of being a Christian and the political expectations of the Roman State came into deadly collision, so that martyrdom resulted.

But at its deepest this is a vision which reminds the Christian community that part of its purpose is to treat people as capable of civic dignity ad civic liberty, capable of that responsible maintenance of their environment by free decision taken in consultation. Because of course the point of having a citizen’s assembly or ekklesia, a Church, is so that responsible citizens can argue about what’s good for the community. The Church, then, from that point of view, is a community where we argue about what’s good for the human race. And we do so in the light of what God has shown concerning the calling and the dignity of humanity overall; because of course this is a city, a polis, which has no ethical or local boundaries, a political community which is in principle open to the whole of humanity. That is one of the things that makes it distinctive. To learn to be a Christian therefore is to learn how to exercise decision-making freedom and the maintenance of your environment in the context of a vision for all human beings, which is one of the things that makes it both exciting and complicated and liable to appalling failures.

A word about some of those failures and some of those mistakes. This potentially quite exhilarating picture of Christianity as a kind of citizenship in an imagined community can go wrong in a number of ways. One of the most obvious is to say that this is simply a rival identity to all other societies: that that there are human societies with their limits, boundaries and rules, and, alongside them, competing for space and jostling for privilege, is the Christian community – the real political unit, the real state with real authority. It’s one of the things that went rather badly wrong in the Western Middle Ages where the Christian Church all too often saw itself as a rival state with a rival government and a rival system of law. This was the state governed by clergy; by the international corporation of real experts with its supreme court in Rome. And it wasn’t that surprising that a lot of medieval monarchs took a rather dim view of this when they were trying to establish their own legal authority in their own countries. A distinguished predecessor of mine, Thomas Becket, discovered that this was not at all an academic argument. It’s also at the root of some of the passion and the suffering of the English Reformation. But that would take me far afield. I simply mention it here as one illustration of what can go wrong – the assumption that if the Church is a kind of political unit surely it must be in competition with other kinds of political unit. And at times both Church and State have fallen into that error, and played out that unhelpful—and sometimes murderous—script.

Equally mistaken or course is the idea that this new citizenship is simply something that goes on inside your head. Your actual political circumstances may be miserable and oppressive but you know secretly and privately that you’re a child of God. You never find ways, or never try very hard to find ways, of expressing that in the world around, and you may even want to discourage other people from seeking to express it. This can lead unfortunately to Christianity being a tool of oppression: ‘Yes, I know you’re poor, I know you’re disadvantaged, I know you have no legal privileges. Never mind, you’re a child of God really. Just don’t expect anything in the outside world to reflect that fact in any effective way.’

Two mistakes about the relation of Church and state or Church and society: two understandable but very damaging mistakes; and if we want to avoid them we have to tread a very complex and delicate path between those errors. We have to find a way of saying the new citizenship is about beings of flesh and blood, and thus we may expect it to have visible and tangible effects in the world. But because it’s a citizenship created by God and effected through the world of God, it’s never simply going to be another system competing with alternative human political systems, because no human arrangement of affairs is simply going to embody the will and the work of God. St Augustine at the beginning of the fifth Christian century treads this complex and delicate path with enormous skill and imagination in his great work on the City of God. It’s a work, as he says at the end of Book 14, which deals with two kinds of human belonging together, and two kinds of love. It’s not about systems or institutions but it is about the way in which human beings visibly live together. Do they live by bearing one another’s costs and one another’s burdens? Or do they live at each other’s expense? At the end of the day, says St Augustine, those are the two great human options. If you go for the first you are moving slowly in the direction of the City of God – the polis, the political reality that the Church represents. If you live by some other principle you’re not just opting for an alternative political system (Augustine says rather sharply and brutally), you’re eventually opting for chaos. And the best you can hope for is indifferently controlled selfishness.

So we’re not talking about rival institutions or rival political systems, but about a spectrum of images, metaphors and ideals of what’s possible for human life together. In Augustine’s world, at one end of that spectrum stands, very clearly, a world in which the citizens are living for one another because of their love of the infinite, the limitless, endless good and beauty that is God: because they are torn out of their selfishness by that love for the divine beauty. They are instinctively generous to one another and able to live by bearing each other’s costs and burdens. And the more you move along the spectrum towards the chaos of selfishness, the more you move away from truth and beauty, the more you find it difficult, baffling, to think about the common good, about a good that is essentially everybody’s, not just belonging to one individual or one group.

You may or may not agree with the way Augustine sketches out the territory. But it’s important I think to recognise that what he is putting before us is an ideal of human citizenship; a way of living out your human dignity in which the capacity to make decisions is real and central and the responsibility for sustaining your human environment is real but is never going to be reduced to one system of management or government.

Oddly enough I think we sometimes see this most vividly expressed in modern situations where the name of Augustine may very well be unknown and some of these theological refinements may not be familiar. What many people will say is that, amid the chaos of developing economies, impoverished societies and failing states, the one source for creative and dependable civic virtue is in communities of faith. It is communities of faith in which people learn to trust and to be themselves trustworthy; in which people learn to take a long view, and to value honesty and dependability; in which people learn to share one another’s costs and burdens – which is why, in so many situations of developing economies and chaotic post-conflict political realities, in many African countries for example and many Latin-American contexts, it is the Christian Churches that are the places where civic, political virtue is taught and learned. I believe it’s very important in our international policy to take with deep seriousness the creative political role of communities of faith, and particularly the churches, in these contexts if we actually want to see people learning civic virtue and shared responsibility.

It’s a message which many of us have been seeking to communicate in recent years to successive government as to how aid and development are best conceived. It’s not always the best idea to route aid through government where government is ineffectual or corrupt. It may be that you have to seek out those institutions of civil society best equipped at grass roots level; and in so many instances those will be communities of faith, close to the grass roots, educating people in trust and trustworthiness, capable of delivery.

And all of a sudden some of these issues have become rather pertinent to the UK. The language, the rhetoric, of the ‘Big Society’ has arrived to stay, whether we like it or not, and is currently puzzling a great many people – puzzling, I hope, constructively (it’s always good to be puzzled in our public reflection on society) because it challenges us to ask questions about where political civic virtue and responsibility are best learned and best exercised. And if the Big Society is to be anything more than a slogan looking increasingly threadbare as we look out at a society reeling under the impact of public spending cuts, then reflection on this subject has got take on board some of those issues about what it is to be a citizen and where it is that we most deeply and helpfully acquire the resources of civic identity and dignity.

About 100 years ago a very distinguished Anglican theologian by the name of John Neville Figgis, a priest of the Community of the Resurrection in Yorkshire, wrote about how the Church should be seeking to shape public opinion. And by that he meant, first and foremost, shaping public opinion within its own boundaries. The Church ought to be a place where people were educating one another about civic questions and human dignity, where people were educating and being educated about liberty, responsibility, the creation of a sustainable human environment. And Figgis said that the significance of trying to shape public opinion within the Church was something quite different from an institutional programme on the part of the Church to impose its vision on everybody else. The Church’s first business, he says, is to live differently, to be the kind of learning community where civic dignity is all the time being developed and explored. And that civic dignity, as it is developed and explored, becomes the organ, or the motor by which people are stimulated to go out into the wider society and talk about, argue about, what is good for the community. We may say that, among other things, the Church is a ‘political seminar’, because it loves and worships a God who transforms human society not just human individuals. Through God’s love, the Church is a place where we argue about civic virtue and common good. And the better we get at that argument within the Church, the better we shall get at arguing in public about the values and visions that we derive from what God has done.

To quote an authority rather nearer home: Graham Ward [Professor of Contextual Theology and Ethics at the University of Manchester] has written about the fluid boundaries ‘between physical bodies, civic bodies, social bodies, sacred bodies and the body of Christ’. A working society is one in which all those kinds of bodies are reflecting on themselves by engaging with each other. Action that shows hope moves ‘in and through’ all of those different kinds of bodies and identities. And once again the body of Christ, the political reality that is the Church is a place where image and ideals and policies are generated and thought through in a way that allows them to move into wider discussion and debate.

If the Church has, as it still has in this society to some extent, a guaranteed public platform by the visibility of the Establishment (even if that is just simply a matter of Archbishops of Canterbury in Westminster Abbey from time to time), then the justification of that is not that the Church has a God-given right to tell people what to do or to think. It is because the kind of argument the Church should be having within itself about human dignity and human hope is the kind of argument any healthy society needs to make room for. And when the religious dimension and depth that is embodied in the vision of humanity that we’re talking about is overridden, forgotten or marginalized, what happens is that politics in the public square ends up operating with a desperately impoverished version of what human beings are like, and what they are capable of. The only justification for the public presence of the Church in British life or the life of any society is in its God-given capacity to keep that argument alive, to remind people that humanity is never exhausted by any particular political definition or social order, that there is always more to discover about human beings made in the image of God. It is that dimension of depth that we are here to celebrate, acknowledge and empower in public debate.

So it’s not a matter of the Church binding its vision to the agenda of this or that party, not a matter of the Church creating a political party to embody its vision and its priorities – another of the mistakes frequently made in Christian history. Much more, it’s a matter of the Christian gospel motivating a grass-roots politics and activism of generosity and mutuality. The polity, the shape of the common life of the Body of Christ needs to be translated into policies and politics. And that is a matter that needs reflection and involves risk and, as we have noted, sometimes real mistakes. But as the Church seeks to nourish and encourage civic virtue, to encourage generosity, mutuality, the bearing of on another’s costs, it will be gaining the authority and experience to talk about this in the wider discussion of our society

So if the Church isn’t running political parties or telling you exactly who to vote for, what is it doing and why might it matter? The Church’s commitment to civic virtue appears in all kinds of grass-roots ways. It may appear in the local parish’s involvement in running a credit union; it may be apparent in the willingness of church members to serve on school governing bodies; it may be visible in some of the enterprises the Archbishop of York and myself have had the privilege of seeing already during our visit to Manchester. But it also shows itself in other more personal ways. Christians are committed to domestic virtue, the virtues of family life, the faithfulness and generosity of personal relationships, promise-keeping and dependability in their sexual relations and honesty in their financial dealings, because they are committed to political virtue, to shared responsibility, bearing one another’s costs, creating a sustainable environment both politically and domestically: the sustainable environment that matters for the bringing up of children in security and in love. So there isn’t a great gap between personal and public morality, between supposedly private issues and political ones. Instead, for the Christian there is a real continuum uniting all of these areas of our lives and decision-making, because in the whole of that complex of activities which makes us human, every area has the capacity to show (or fail to show) the basic virtues of faithfulness, generosity, awareness of and sensitivity to the needs of the other. A marriage, a family, a governing body, a credit union, a farmers’ cooperative, a project for those young people excluded from schools: all of those things and many more are the ways in which Christian politics first becomes apparent. And the Christian citizen who has learned these citizen’s virtues in the Church through the language of the body of Christ is then called on to go out and make sense of all that in the policy-making and decision-making of a wider world, where those visions and values are not taken for granted. That’s where we have to have the argument. And that’s why I find it a little odd sometimes when the right-thinking or left-thinking critics in the media say that the Church should not be in the public arena because we do not want the Church to tell us what to do. I don’t particularly want the Church to tell everyone what to do, either; but I want the argument in public to be real and honest, a genuine argument about what it is tat makes a good citizen, a good city and a good society. And because I’ve already mentioned the significance of some o f this in terms of international development I would just add hat the Christian living in a universal society, a society without local and national boundaries – the Body of Christ, is bound to take it for granted that the welfare, the well-being, the cost, the suffering and the hope of any other human society on the face of the globe, is involved with their own. Once again there is no great wedge to be driven between the local and the global.

Now that of course does finally suggest there is a strong critical dimension to Christian citizenship. I’ve sketched a picture of the Christian citizen as somebody prepared to have arguments in public. I hope that doesn’t suggest simply that the Church is educating people to be a public nuisance and no more, though there are many creative ways of being a public nuisance in a democratic society. I hope Christians will be working at good ways of doing just that. It means that there can be no Christian citizenship without the Church nurturing in its members a certain ‘nose’, a certain instinct for the dishonest, the shabby and the evasive in public life. There ought to be a lie-detector being implanted into the Christian citizen. The Christian citizen is somebody who ought to be critically aware of when it is that people in public are using rhetoric that demeans or diminishes human beings, when they are telling lies about what human beings are really like.

There’s a powerful passage here from Jim Wallis, the great American Christian political commentator, in his book God’s Politics (there’s an ambitious title for you); remember that it’s written in the context of the USA: ‘Politicians try to makes us afraid of the problem and then they look for somebody to blame for it. Then they watch to see whose political spin succeeded either in the next poll or the next election.’ What he is saying is that when politics is dominated by the language of fear and scapegoating the Christian lie-detector ought to be springing up into operation. This is not real politics. This is playing with fear and paranoia, and games about blame.

The word ‘prophecy’ is thrown around quite a lot in talking about the Church’s involvement in politics. People sometimes say that the Church is not being prophetic enough; they want to know why archbishops, among others, are not being adequately ‘prophetic’. They claim there is a prophetic role for every Christian in public – and I understand what all that’s about. The word is an important one, and because it’s important we need to use it correctly. To be prophetic is not simply to be negative, critical – or just loud. To be prophetic is not making radical noises: in this context it is about trying to identify the truths that lay beyond party squabbles and short term advantage, about trying to identify what it is that lies beyond winning and losing in the secular political game. It is about being politically and civically virtuous in the way I’ve been trying to describe, and encouraging the Church to be itself: that is, to live differently, to form intelligent prayerful public opinion within its own membership, and then to move into the risks of argument.

So our calling is indeed a ‘prophetic’ one, and to exercise it properly we need a great deal of self-awareness and a great deal of patience – which is not a virtue that always goes with being prophetic. But this is patience in the sense of letting ourselves ‘see’ those truths that are beyond the winning and the losing, beyond scapegoating, blame and fear. At that level I make no apology at all for saying the prophetic and political calling of the Church requires Christians also to be, in some degree, contemplatives. The capacity to be quiet enough to learn is essential in all of this, and the word contemplative is really just a rather long and frightening version of having this capacity to be quiet enough to learn.

How do you define a citizen? And how does the Church contribute to the identity of a citizen, to civic virtue and welfare? By treating everyone it encounters within and without its boundaries as potentially an adult agent; as somebody capable of grown-up action, self-aware, self-critical, willing to carry the cost for others, not only to talk about the cost to themselves; someone ready to take responsibility for taking meaningful decisions, decisions that communicate something in a community, and to create the conditions which help other people’s decisions to be meaningful in the same way by being creative and communicative within a shared life. To be a Christian, a member of the ekklesia—the Christian citizen’s assembly—is to seek to grow up into this responsibility with self-awareness, with repentance (because of all the ways in which we can get it wrong), to think and act and speak for a common good set before us in that transforming vision of the Body of Christ – the community in which no-one lives for him or herself alone.

The bold claim we make in confronting the wider political discourse of our society here and now in the UK, our global society today, or any imaginable human society, is that this kind of adult, mutual, self-aware, responsible, and thoughtful virtue is the heart of any sustainable civic freedom, any sustainable or lasting political well-being for the human world. People may or may not agree with that claim, but I hope you might think it’s certainly worth discussing.

© Rowan Williams 2011