'Faith, Reason and Quality Assurance - Having Faith in Academic Life'

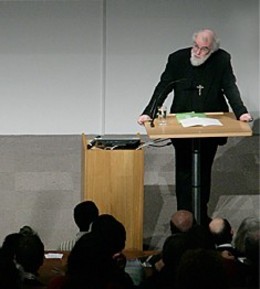

The Archbishop, Babbage Lecture Theatre

The Archbishop, Babbage Lecture TheatreThursday 21st February 2008

A lecture by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, held in the Babbage Lecture Theatre, Cambridge. The event was part of "A World to Believe In - Cambridge Consultations on Faith, Humanity and the Future".Click links on the right to listen to the lecture [29Mb], and the question & answer session that followed the lecture [11Mb].

Read the transcript of the lecture below, followed by the questions & answers - or click here to go directly to the Q & A transcript.

Transcript of the lecture:

'Faith, Reason and Quality Assurance - Having Faith in Academic Life'

I want to begin by referring to a habit of thought which was once prevalent in Roman Catholic theology. Roman Catholic theologians sometimes used to talk about the Church as a societas perfecta – a perfect society; and when people had stopped laughing unkindly, they would explain that what this meant was not that it was a society of perfect persons, but that it was a society existing for goals which it itself specified. The Church was not a sub-committee of anything else. It wasn't a 'sub-contracted' reality, it set its own agenda, and it didn't exist simply to serve the ends that others prescribed for it. What I want to reflect on with you this evening, is what it might to think of the university as a perfect society - that's to say, as a society of people who, broadly speaking, set their own agenda and decide for themselves what they're about.

Centuries ago St Augustine – quoting an even older authority, Cicero – spoke about how communities were unified by the objects of their love. A political community was one where people cared about the same things, and the deepest kind of coherence in any kind of political society was that shared care about the same things. It's another way of making exactly the point that I wanted to make by referring to the 'perfect society' model. What gives coherence and integrity to this kind of human association is not a programme that is fixed from beyond, it's a sense of shared care. And historically the universitas studium, the universe of studies that makes up the university, has cared corporately about the life of the mind. What has made it a society within itself, has been that priority of nurturing the life of the mind.

In case we get a bit romantic about the history of universities, it's important to remember that this has never meant nourishing the life of the mind solely for itself. Universities have never just been places of contemplation. They have been that, and very importantly that, but there's always been more to it. Universities have a long history of orientation towards government and administration. At some point in the histories of universities in Europe, and this country very particularly, one of the main purposes of universities came to be the training of a governing class. This is a very ambivalent legacy, but a reminder that the life of the mind isn't just the life of contemplation.

But in so far as universities have cared about training people for public life, for government and administration, they worked on a buried but very serious assumption that part of what equips you to make decisions in the social world is being able to know what a good argument looks like. It you're going to be a decision-making citizen, you need to know how to make sense and how to recognize when somebody else is making sense. You need to know what arguments are communicable to other people and what aren't. You need to know how to share forms of argumentation. When people don't have methods of argument in common, they can't even have intelligent disagreement, they have a fight; and you could say that one of the purposes of universities is to stop people having fights. Which is not to say the universities are not notoriously conflict-ridden institutions! But there are ways and ways of fighting, and that kind of conflict which depends on people recognizing in one another something like the same processes of making sense is part of the university's public responsibility, part of training people to make decisions in a social world, to communicate those decisions, to win ownership of those decisions, to move forward collaboratively.

So, higher education, like other forms of education, is a training in what you can trust and what you can share, what kinds of argumentation you ought to be able to trust and what you shouldn't trust. We sometimes rather over-emphasize the role of education in teaching you to be suspicious; important as that is, to teach people how to be suspicious ought also to be to teach them something of what they can trust; what meaningful action together is like; how arguments and priorities and visions can be communicated; how common languages can be shaped. And that in itself means that in the enterprise of education at every level but very specially in higher education, faith and hope are at work and they're at work in the training of reason.

Faith and hope – faith as the capacity to trust arguments that can be shown to be trustworthy; hope as the conviction that it is possible to act collaboratively in human society, not just with endless rivalry and jostling for position; and I'd like to think, although it's not always a virtue associated with academic life, that charity comes in somewhere as well. Charity; in the sense of a generous awareness that there are different ways of making sense, there are different sorts of good questions to ask about the world we're in and that insofar as those questions are pursued with integrity and seriousness, they should be heard seriously and charitably. All of that, to my mind, belongs with seeing the university as a society devoted to the life of the mind. It may serve the wider social world, but its duties are not simply prescribed by the wider world. It will nurture and encourage people in the skills and virtues they need to be social decision makers, but it won't exist to solve the problems of the world around in any very simple way.

But that means that there is a perpetual challenge to the university from all those forces that are reluctant to let anybody other than public authority set agendas. The university stops being a society, a perfect society, stops being a place for training people in critical public engagement, when society at large attempts to dictate requirements. And that can happen in a lot of different ways. Throughout the history of university education, universities have at various points been turned fairly effectively into tools of political propaganda. I'm sorry to say that even some of the great chairs of some of our historic universities were founded by the state in order to propagandise for its policies. More recently, and more horribly, in the twentieth century we've seen in Nazi Germany and in Eastern Europe how universities can be conscripted into the service of tyranny. And anyone disposed to be optimistic about the strength and integrity of the life of the mind in a university institution ought to read and ponder some of the history of universities in Germany in the nineteen-thirties. It's depressing and instructive to see how even great historic institutions can at times buckle under intense political pressure and turn into something other than themselves. But equally, the university stops being a university when it is just a kind of reference point for problem-solving, when the state or society at large, simply passes down (and the word down is important) to this little group of specialists a set of questions to which they're expected to produced neat and conclusive answers; to establish the facts so that decisions can be made.

So, throughout university history, there has been that tension between the university as a society, equipping a certain kind of critical skill and excellence; and the university as a temptingly useful tool for other people either to advance their political agendas or to solve their social problems. In our age, those pressures are no less severe than they've ever been. And I think it's very interesting, as you look across the history of universities, to follow the changing patterns in how benefactions are made. What do people give money to universities for? In our climate the simplest, most attractive prospect for money-raising is very often a project with clear outcomes. In earlier generations the classic form of benefaction was to community life: it was the endowment of some aspect of collegiate life as often as not. Further back in the Middle Ages of course, it was frequently prayers for the souls of the departed - and while I regard that as an entirely worthy, proper and possibly entirely necessary contribution to the eternal life of people in and out of universities, it's not perhaps the most obvious priority for the present day! But if you look at those shifting patterns of benefaction you'll see how what once was a fairly obvious and compelling form of doing good to a university, helping to structure and resource a community, can give way over the centuries to the temptation to think the most obvious, natural and important thing you can do is to finance a project with a beginning, an end and a set of outcomes. I don't make any comment on the various excellences of these forms of benefaction, I simply note that that is a trend, and maybe one that we need to think through a little bit further, to explore whether in fact we have got things a little bit imbalanced. But in such a climate, where there is strong and insistent emphasis on outcomes, on functions and problem-solving, there's a sense in which faith becomes a bit harder in a university climate.

The prescription of what matters – whether it's in terms of political agendas or problem-solving exercises – is always going to rub against and sometimes seriously undermine the idea that the university's primary task is to help people discriminate in argument so that they may be better decision makers. It's the area of university life which the Regius Professor [Professor David Ford, chairing the lecture] has so eloquently written about in terms of the 'wisdom' appropriate to university life. A university as a society committed to this critical task is a society interested in forming people who have a discerning attitude to language. By this I don't at all mean that they should all be literary critics, because scientific argument is about discerning our relation with language just as much as education in the humanities. Scientific education too is about recognizing a good communicable argument when you see it, about shared language and shared proofs. And to say that the role of the university is focally about helping us to have this discerning approach to language is not to say that the university is committed to – in the narrow sense – rationalism or intellectualism, but to say that it is rather about the forging of the proper medium of human exchange. The good of a university, what justifies it at the end of the day, must be in this valuation of critical discernment in the service of common life.

This is to say that part of the function of a good working university is to form critical and active citizens. The critical or active citizen is not somebody who will necessarily accept without question what somebody tells him or her they ought to be accepting. A critical and active citizen is not one who regards the business of social life simply as problem-solving. The critical and active citizen is someone who is prepared to set high standards for communication, to ask hard questions about who and what is to be trusted, and to be committed to finding ways of working together that are honest and constructive, the language that we share. And it's interesting that bits and pieces of writing about the priorities of the university in the last ten or fifteen years have more than once come back to underline this question of the university as being responsible for citizenship - not by laying on courses in citizenship, as you might do in a secondary school, but by equipping people with the skills and the virtues that you'd need to be a critical and active citizen.

I think that's quite an important point in its way. Because for some people, if you object to or raise questions about the idea of the university as a problem-solving institution bound up in projects with clear outcomes, they will sometimes say 'but surely you can't believe the university is just there for the life of the mind, for contemplation alone, in this age?' But between a picture of academic life which is all about pure, contemplative study and a picture that's all about functionalism and problem solving, I would say there is this middle ground which connects those two, training in 'a discerning attitude to human language'. The purely contemplative bits of study, the apparently useless bits, are themselves a reminder that the mind is a hungry and sometimes almost indiscriminately hungry thing. It looks to find things out, it seeks to understand, it assumes it doesn't know things and it absorbs information on all sorts of matters and reflects whether or not that appears to be instantly a problem-solving mechanism. But those critical skills which are bound up even in the most contemplative of study all have their use in shaping the critical, active citizen. So it's a false antithesis to say either the university focused entirely on problem-solving, on contracts from industry and government etc, or a university locked up in what's assumed to be a seventeenth or eighteenth-century model of entirely introverted, contemplative scholarship. Somewhere in between is the university as the nursery of citizens: the university as a society with its own particular excellences in this training of a discerning attitude to language, looking towards a social good which is discovered and developed through rigorous and honest argument.

The University College of Christ Church, Canterbury (a new-ish foundation in terms of university status) puts on each year a series of open lectures, and I was delighted to discover as I was preparing my thoughts for this afternoon that on 12 March, Professor Jon Davidson of the Templeton Project 'Learning for Life' is giving a lecture in Canterbury entitled, irresistibly, 'Mr Chips to Postman Pat: how we stopped teaching and began delivering a curriculum'. I don't know what Prof Davidson is going to be saying, but it sounds as though he is going to alert us to some of the dangers of the metaphor of delivery where education is concerned. If we're talking about education as a formation, about the critical mind and the discerning attitude to language, delivery as of something prepared and packaged and self-contained, is never going to be a helpful metaphor. It may indeed be a deeply corrupting metaphor. If we care about formation in this context, about the university as a place where people learn to be a certain kind of human being, as well as everything else, then we ought to maintain a high level of skepticism about the language of delivery. However often and however respectably it's used, it carries with it a lot of dangers.

To speak in those terms, of the delivery of something pre-packaged and self-contained, begins to push aside the idea that what I'll call a critical humanism is possible. That is, 'humanism' in the sense of a rich and resourceful approach to what human beings are capable of, intellectually and socially; critical humanism because it's a style of living and thinking that assumes there are always questions to be asked, and nobody else is automatically entitled to tell you to shut up when you ask them. And that trust that critical humanism is possible, a critical humanism which in other contexts I've once or twice described as an 'argumentative democracy' is, I would say, something profoundly connected with religious commitment, surprising as that may sound.

And in the last part of what I want to say, I want to underline that dimension of connection with the religious vision. In a modern university, threatened or seduced at times by these pressures towards delivery and problem solving and functionalism, there is a very particular role for all kinds of humanistic perspective. That perspective may come from the arts or from the sciences, but there is an even stronger, more marked role for the religious perspective. Because one of the things which theology in the university ought to be saying to the institution as a whole is that there is in the broadest sense an 'anthropological' perspective, a doctrine about human nature, involved here, which frames our human questions.

Religious belief is not only belief about God, it's belief about human beings. And what is non-negotiable in faith is not simply a set of doctrines about the transcendent, but a set of commitments about how human beings are to be seen and responded to. Not everybody in our society has an anthropology, a doctrine of human nature, not everybody has a set of such commitments and they probably never will. But it is a very impoverished society, and it is a very limited educational policy, that assumes you can do without the memory of such doctrines and commitments around. Christian anthropology, the Christian vision of what human beings are about, assumes a number of things about humanity which shape Christian responses to human existence. It assumes that human beings are summoned to respond to an initiative from God, that human beings are summoned to shape a life that will itself communicate something of God to others, and something of humanity itself to God. It assumes that humanity is called to question fictions about both the society and the human self in the name of some greater destiny or capacity in humanity than most political systems or philosophies allow. So, properly understood, Christian anthropology – the Christian doctrine of human nature – is one of those things which ought to reinforce in the university and in society more widely, a set of deep suspicions about the ways in which that range of human capacity is shrunk by political expediency and convenience.

I spoke last night about how religious faith rightly understood brought one to a place where you could see more rather than less of human complexity, richness, tragedy and fulfillment. And perhaps our current discussions about the place of theology in the modern university should consider this. I say this, conscious of the fact that that place is not taken for granted by everybody, that the role of the university in collaborating in the formation of Christian and other religious pastors, is not particularly secure at the moment. And I know that the discussion of that issue has raised in some quarters, the not wholly unfamiliar cry that theology has no place in a modern university because it works with a whole set of unexamined beliefs which can't be proved by simple evidence - rather like approximately 60% of the university curriculum anyway. I don't believe that to defend the role of theology in the university is automatically to say that universities have to be respectful and uncritical about confessional allegiances, to expect that everybody studying theology will have a religious belief. But at the very least, to have a sophisticated and well-resourced theological component in the life of the university is to be reminded that there are communities which historically have certain commitments about what is non-negotiable in human nature. I think that does any institution, any society, any university, the world of good. What is horrible and tragic about the history of universities in Germany in the nineteen-thirties, is that quite clearly a very large number of academics allowed themselves to be convinced that there were certain aspects of human nature and human dignity which were negotiable after all. Sadly, the presence of theologians at many of those universities didn't necessarily save them. But it's reasonable to ask, at least, how much worse the situation might have been had there not been those theologians like the great heroes Karl Barth, and his colleague Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who as theologians reminded the academic institution and the academic world of their day, that at the very least there had been people who believed in non-negotiable things about human nature. And a university pretending to have a synoptic comprehensive view of the human project could not ignore those traditions.

So the subject matter of theology for the believer may be the relations of God and the human world and the non-human world that God has made. But the subject matter can also be, at the very least, the phenomenology of this kind of critique which arises from faith, the phenomenology of an imaginative form of life in which human beings are cast in unexpected, awkward, surprising and sometimes glorious roles in the narrative that faith relates. If that is truly part of the university's corporate self-understanding - that it is there to bring in, understand and work with some such visions of what humanity is like - I think the role of theology in the university is reasonably assured. And as that living sense of the university as a society, a societas perfecta - a society that sets its own agenda and defines its own forms of excellence - comes increasingly under pressure and seems sometimes to be shrinking in an unsympathetic and social climate, I suspect that we may find, to our surprise, that theology may be a more rather than a less essential part of the landscape of a university that is trying to do what it wants to do and what it is equipped to do, to create critical discernment about human language, to form critical and active citizens, to help people recognize when sense is being made and what sorts of discourse can be trusted. I'm struck by the fact that it is still possible to have these arguments in our universities, particularly here in this great historic institution. We are beginning the celebration of the eight-hundred years of this university's existence, and it would be a rather sad paradox if that eight-hundredth anniversary was marked by the down-grading of the study which, at the very beginning of the university's life, seemed to be the most comprehensive and the most resourceful of all: the study of theology.

But, in conclusion, don't let me give the impression that this lecture has been entirely about special pleading for the status of theology, not even with the Regius Professor at my right hand! It has been rather, an argument about what I've called a critically humanistic approach to the university. My great predecessor, Michael Ramsey, worked very hard to reclaim the word 'humanism'. He believed that it was one that had been unfairly and unhappily kidnapped by those who used it to mean an essentially non-religious view of the world, and he more than once preached and lectured on the subject of Christian humanism with, at the back of his very capacious and considerable mind, that wonderful statement from one of the early Church fathers [St Iraeneus]: 'The glory of God is a human being fully alive. The life of humanity is the vision of God.' That full aliveness of human beings includes surely, focally, centrally the capacity to ask the right questions, the capacity to know what is to be trusted and what is not to be trusted, the capacity above all to find words in common that enable acts in common to prevent us from the literal madness of isolation and self-destruction.

I hope, then, that, as the university celebrates this anniversary, such a critical and humanistic perspective will be very much at the heart of its discussion, so that the next eight hundred years may be again a record of people being trained in those critical skills of decision-making and collaboration, which are part of the glory of God.

© Rowan Williams 2008

Questions and Answers following the lecture:

Question:

How can citizens who are unable to study at university become better citizens equipped with critical and discerning decision-making skills? Should more citizens be encouraged to attend universities to develop these skills and virtues?

Archbishop:

I very much welcome that question because it does remind me, first of all, that the university can be a privileged environment for the formation of the critical mind and that not everyone has that privilege. And therefore, secondly, issues around access are crucial. How are these skills and critical virtues communicated? Universities have got better as time has gone on, I think, about their interaction and outreach with the community, and in my time as a Bishop in Wales I was privileged to sit on the governing body of a very different academic institution: the University of Wales College, Newport, an institution profoundly committed to access, an institution which worked intensively and very imaginatively with a deeply deprived and depressed region of South East Wales, making it possible for some of these skills to be developed. And I think that is part of the answer: universities need to work repeatedly at that issue of access. Sadly, we're often confronted with what I think is a false antithesis between access and excellence in higher education. I don't think that's a necessary stand-off, but working it through is not easy. I welcome the question and think that widening of university access within the framework of some clear understanding that what you're trying to do is not simply produce people with qualifications but people with qualities ...

One of my tutors was fond of saying that the most interesting figures in the history of ideas were those who turned out to be wrong. How might universities encourage the excellence of being wrong.

I think the answer is partly that a university ought not to see itself as primarily a risk-free, sanitized intellectual environment. The history of our intellectual life in this country and Europe more generally and the world at large is of course a history of risk-taking. The history of science is a history of risk-taking. There would have been absolutely no advance in science at any point had people not been willing to make fools of themselves, to offer wrong answers to questions that nobody else seemed to be asking but which needed asking. So, I think there's a very considerable place for being wrong in university life. Heaven help us if the first consideration of any working intellectual is 'how can I be absolutely sure I'm not making a mistake?' That's a recipe for absolute stasis, I think.

Can you say more about the skills, dispositions and virtues of the teacher in a university context, from a theological perspective?

There's been some quite interesting writing about this in recent years and I would say that the skills of a teacher are primarily those of a learner. By which I mean a good teacher is somebody who has not finished with his or her subject and whose engagement in communicating it is part of their own exploration. Which is why I think a glib and facile separation between teaching and research will never be for the good of any university or any intellectual institution. A good teacher is a good learner who in communicating what he or she loves, and is committed to, is themselves developing. That means of course that a good teacher is a good listener as well as a good speaker, someone who is prepared to learn even from their students. When I look back on nearly twenty years of university teaching in my own life, I can without exaggeration point to perhaps four or five moments when students of mine have said things to me that have actually changed my perspective for good and all. Not necessarily even that they have argued me out of a position, but that simply by coming to a field or subject new to them and just a little stale to me, have made me think afresh. And my most vivid memory of that kind is of one of my students, now a distinguished cleric in the Church of England, saying to me as I was trying to explain a theological point to him '...but why is that a problem?' and he was absolutely right to ask that. I'm still asking about that particular subject! But that's some of what I'd say about the virtues of the teacher. And from a theological perspective more specifically, I think that in the New Testament there is in the letters of Paul especially, there is a wonderful kind of shot silk, double-sided portrayal of the Christian teacher who is also, in communicating truth, discovering it. I sometimes used to say to my students that St Paul didn't know he was writing the New Testament, so his argumentation is not tidy and his prose is convoluted, and he is feeling his way into a deeper understanding of the truth as he communicates. Because his primary sense of what his duty is as a teacher, is to let truth be in him, not to describe it, categorize it or imprison it, but to let it be. Theologically, I'd say that's where teaching begins, can truth find a home here, and be alive?

Do you believe in ultimate truth?

The answer is yes. I don't believe that the world is simply the construct of what we choose. I don't believe that the world is a kind of minimal agreement about what we can just about manage together. I believe the world, because it comes from the hand of an absolutely real God, the world is thus and not otherwise, and that education therefore is always education in reality in knowing how to relate to a truth, a reality, a life which doesn't change as we do. And it's precisely because I do believe in ultimate truth that I'm wary of premature attempts to say 'and we've now got it', because of its solidity and infinity, it's glory, we have to be very cautious about supposing that we have it now wrapped up, though we can believe it draws us and compels us and has authority over us.

Why does society find it easier to admire excellence in sport and the arts etc, than excellence of the mind?

I guess it was ever so, though there are societies other than ours which seem to be a little more generous to the life of the mind than we sometimes are. But I wonder if it's something to do with the sheer fact of performance? You know what it looks like for somebody to be good at sport, you know what it looks like for somebody to be a great artist. What does it look like for somebody to be a great mind? Imagine a great mind, and all you can think of is probably some bloke, sitting in a study somewhere, looking slightly pained. As performance goes, that's not very exciting! We are a very image-obsessed, performance-focused culture aren't we? And I suspect it may have just a little bit to do with that ...

Several linked questions:

How far do you think reason and science should approach religion and the question of God's existence?

God is outside time and space: why would he care about us who live in such a minute part of it?

If God cannot be demonstrated with evidence, in what sense can he be said to exist? Isn't it avoidance of argument to say it's down to faith?

In all sorts of areas of our human life we make commitments that are not absolutely compelled by evidence. We do what the late, great philosopher Gillian Rose called 'staking ourselves'. There is enough to make us feel compelled or drawn by something, to say 'here I must be.' And I take the risk of moving into that space where I'm committed. It's not peculiar to religious faith, though religious faith is a particularly sharp and extravagant form of it. And that means that when we look academically at what faith is all about, two things at least are going on: one is the very general work of mapping out some of those things in the human world that do as a matter of fact, rightly or wrongly, draw people to the edge of commitment. What are the sorts of argument and the sorts of experience that impel people to the edge of commitment? We can at least look at how that happens. And then we can look at how people argue when they are committed. How do they draw conclusions about the divine and the interaction of the divine with the human world? What do their arguments look like when they are committed? And in between those two moments is of course, that inaccessible and mysterious moment of transition when you make the commitment, when there is a choice. And while the academic analysis could say quite a lot about what happens on the way to that and what happens after it, there remains somewhere in the middle something which does resist pure academic study. I hope that's not too evasive an answer, because I think it's not quite as uncommon a feature of our human existence as we might think uless we have a rather simplistic view that we always act when the evidence has stacked up and we can say 'allright, there's really no decision to be made, that's the obvious thing to do'. In how many areas of our lives or even our intellectual lives, do we actually work like that? Not all of them: which is why I said that quite a lot of what goes on in a university is actually the study of things that are not wholly unlike religious faith.

© Rowan Williams 2008