'What Difference Does it Make?' - The Gospel in Contemporary Culture

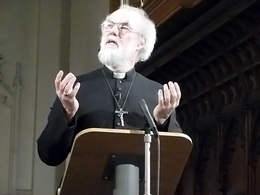

The Archbishop at Great St Mary's Church

The Archbishop at Great St Mary's ChurchWednesday 20th February 2008

A lecture by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, held in Great St Mary's Church, Cambridge, as part of the "A World to Believe in - Cambridge Consultations on Faith, Humanity and the Future" Sessions.Click links on the right to listen to the lecture [42Mb], and the question & answer session that followed the lecture [27Mb].

Read the transcript of the lecture below, followed by the questions & answers - or click here to go directly to the Q & A transcript.

Transcript of the lecture:

'What Difference Does it Make?' - The Gospel in Contemporary Culture

I want to begin with a mention of one of the great classics of Cambridge literature. Some of you will I hope have read Gwen Raverat's book, Period Piece: a Cambridge childhood (those who haven't have a pleasure ahead of them). In it she gives a picture of her family, an Edwardian, academic family, the Darwins in fact. And among her uncles and aunts are several figures of ripe eccentricity. One uncle was absolutely convinced that whenever he left the room the furniture would rearrange itself while he was out. He was constantly trying to get back quickly enough to catch it in the act. Now, that is admittedly a rather extreme case of Cambridge eccentricity, but I suspect that it may ring one or two bells with some people around here. How many of us, I wonder, as children had that haunting suspicion that perhaps rooms rearranged themselves when we were out? Wondered whether what we were seeing was what still went on when our backs were turned? And I want to begin by thinking about that aspect of our human being in the world which is puzzled, frustrated, haunted by the idea that maybe what we see isn't the whole story, and maybe our individual perception is not the measure of all truth. Our ordinary perceptions of the world around are often jolted by grief or by joy. They're jolted in a way that leads us to want to say thank you, even if we don't know what to say thank you to or who to say thank you to. They're jolted when we don't know what to do with feelings for which we haven't yet got words or strategies. And that may be a long way from Gwen Raverat's uncle, but something of the same thing is going on. What if the world is not as tame as I'm inclined to think it is? What if my perception of things is not the measure of everything? In a sense the old chestnut is true. Religious feeling and perception in the world is based on, or related to, at least, a sense of human limit, human weakness if you will, but certainly related to the sense that to be human is not necessarily to be at the centre of things, or to be in control of things with a kind of lighthouse vision that, circling about the entire scope of reality, lights up everything with an even light centred in me, my mind or my heart.

But there are two things we can do with this–one of them healthy and one of them not so healthy, one of them leading to terrible religion and one of them leading to faith. Terrible religion happens when we use our religious language, our religious stories, as a way of pretending to ourselves that we are after all in charge, that actually we really are the centre of things and our limits can be overcome. We have access to absolute and infallible truth, to an even and just perspective on all things, we know what the world is really like and there's no more to be learned. It's terrible religion and it's also a terrible form of humanism and those who might have read Prof John Gray's books Straw Dogs will recall that he speaks there about the way in which Humanism itself, purportedly atheistic, still clings to certain religious ideas – or bad religious ideas – by pretending that human beings can actually answer all the questions they set themselves and overcome all the limits that might threaten their power. And the trouble with bad religion, what makes it terrible, is that it's a way of teaching you to ignore what is real.

Now, I'm going to suggest this evening that one of the tests of actual faith, as opposed to bad religion, is whether it stops you ignoring things. Faith, is most fully itself and most fully life-giving when it stops you ignoring things, when it opens your eyes and uncovers for you a world larger than you thought–and of course therefore a bit more alarming than you ever thought. One difference that faith makes is what more it lets you see, and how successfully it stops you denying, resisting, ignoring aspects of what's real.

I used to know a very remarkable man who was for twenty-six years the Senior Consultant Psychiatrist in Broadmoor–one of the more testing jobs that anybody could have–and he was a great Shakespearean enthusiast. One of his favourite lines from Shakespeare was from The Tempest where Prospero says to Miranda at one point 'What seest thou else?' and he said that that was the question that kept him going as a Psychiatrist. Confronted with horrendous and tragic situations with people deeply disturbed, locked up in their own fantasies, he would have to ask himself repeatedly 'What seest thou else?' what more is there to see? And for him, the enterprise of religious faith was about that seeing more, seeing that the world can't be fully seen just by one pair of eyes, that the world can't be fully seen even by the sum total of all pairs of human eyes, seeing that the world has a dimension of real strangeness, a depth not sounded. It's the area where religious faith most overlaps with art, but also with creative science. Creative science, remember, begins in that conviction that there is something not seen, there is something that I or we have been ignoring and it's time we stopped ignoring it. But the arts themselves are rooted in that feeling that the world is more than it shows to any one person in any one image at any one moment.

I want, in other words, to speak about religious faith as a process of educating our vision and educating our passions; educating our vision so that we understand how to see that we don't see, how to see behind surfaces, the depth that we're not going to master; educating our passions in the sense of helping us to grow up 'humanly' in such a way that we don't take fright at this strangeness and mysteriousness and run away for all we're worth. Faith, is inhabiting a larger world. I often find myself saying that one of the problems of perception in our world today is that it so often looks as though faith leads you into a smaller world and makes smaller human beings. Whereas those of us who try to live with and in it would want to say, actually it's an immeasurably larger world.

There's a famous sixteenth-century woodcut which you sometimes see reproduced in history books, which shows a human figure pushing its head through the firmament of heaven–the smooth, tidy firmament of heaven with the little stars on it–this person has pushed through it and is suddenly looking up into a sky that he's never seen before, packed with strange stars. And that woodcut is often taken as a kind of image of what it felt like in the sixteenth century as the Renaissance unfolded, and people realized that the world was immeasurably bigger than they'd ever thought. It's quite often used as an image of resistance to traditional Christianity and religious authority. Yet I want to say that it ought to be an image of authentic faith, of a real understanding of what the tradition of religious practice does for you, pushing you through the smooth painted surface, out under a sky with stars you've never seen. All of that is by way of generalities about religious faith. And I want to move on from there to something a bit more specific.

The same theme recurs in all kinds of religious practice, from the most basic superstition to sophisticated Zen meditation. The same theme: the self is not the centre that we thought it was. There are things you're not seeing, and you'll never see them so long as you think of yourself as that solid lighthouse tower, planted in the middle of the world shedding equal light all around. But how does that play out specifically in the context of Christian faith? In that spectrum of religious practice, where and what is the Christian gospel the distinctive good news? And why might that be worth taking seriously?

And so I'm going to stop talking anything resembling philosophy for a bit and turn to the Gospel according to St John. Because I can't actually think of anywhere better to start in trying to spell out a little bit of what the Christian story of seeing looks and feels like. Those of you who know the gospel of John will recall the story of Jesus healing the man who's been blind from birth. And towards the end of that story Jesus has a sharp quarrel with some of the religious experts of the day, and he says to them: 'Because you say we can see, you're stuck in your guilt. Only if you know you can't see can you find your way.' It's one of those many startling paradoxes that that gospel is full of. Jesus is addressing the religious experts of the day and effectively saying 'Your problem is that you can't see that you can't see'. 'You can't see what it is that your habits, your status, and your skill prevent you engaging with.' And as the gospel story unfolds, we get a clearer picture of exactly what it is that these experts can't see. They can't see the mechanisms that drive them: mechanisms which lead them to be deeply afraid; mechanisms which allow them to use violence to protect their safe and self-justified positions; mechanisms that allow scapegoating, that allow security at the expense of others. They can't see all of that horrible, noisy, mechanical stuff going on inside them and they are stuck with their guilt, says Jesus. They don't know they can't see and when vision is offered to them, they run from it. Well, that's not entirely surprising, most of us when we're offered by candid friends or even more candid enemies pictures of what we might really be like, are inclined to run. Very few human beings, whatever we may like to tell ourselves, have a natural taste for hearing the truth about themselves. When somebody says to you 'Do you really want to know what I think?' the honest answer in most cases would be 'Actually, no'. So, so far, so obvious, you might say and you might feel you don't entirely blame the religious experts in the fourth gospel for panicking at the prospect of being shown the mechanisms of their own fear and their own violence.

But what makes the difference in St John's gospel is that the vision is not only the vision of yourself – a failing, ignorant, frightened self. The story of Jesus as St John tells it, is about a vision of something else which he calls glory; glory, the radiance and the beauty which is at the root of everything. In the light of that radiance, you can't keep up the pretence of self-justification and self-protection. In the full light of that radiance, you can't be like the religious experts and say 'I see, I've got it', and put the experience and the knowledge in a package in your pocket. And Jesus' mission in this gospel is described very clearly as the process of bringing that radical, radiant beauty to light in this world in such a way that only the most resolutely self-justifying and the most terminally terrified will want to resist

And self-justification, fear and violence and all the rest of the package, these things become impossible in the light of that radiance, because according to the gospel the radiance itself is the presence of an utter unselfishness at the heart of everything. What lies behind and beneath all reality, the gospel says, is an action whereby the most full, powerful, resourceful reality you can imagine, lets go of itself, makes over its own fullness of joy and life so that there may be life in another. It begins in eternity; it fleshes itself out time and again in the world's history. The radiant beauty – the glory – of that gospel is the glory of a divine letting go, and faced with that we're delivered, so we hope and pray, from the prison of violent self-justification. Why? Because if we are faced with that vision of an endless, unlimited unselfishness, we have no one we have to persuade to love us, we have no hostile, defensive, cosmic tyrant somewhere over there that we have to placate. All we have is an endless gift of unconditional love. All we have is what again in the fourth gospel we see referred to as an unceasing work, an unceasing labour of giving life. At one point in the gospel Jesus is defending the fact that he's breaking the Sabbath by healing somebody, and he says, 'My father is still at work, and I am still at work.' There is no interruption possible for this unselfish act of life-giving, healing restoration and affirmation.

And again we can perhaps recognize what a wonderful truth that would be, if it were true. And we might wonder how, precisely, such a vision could come to feel natural or possible for us. But that's where the story winds the tension more and more tightly. As the story unfolds, we begin to see more clearly just how tightly we are locked in to our self-deceptions. Gradually, as the story goes on, we see more and more deeply how and why human beings want to resist that double vision, the vision of their own fear, and the vision of the love that overcomes it. And it seems as though fear wins. Jesus is condemned and executed. The refusal to see finally means his death on the cross. But, says the gospel, that death on the cross is itself a moment of glory yet again. Because there we see what a complete letting-go of the self in love, might look like. The symbol is lifted up before us, the symbol of a love with no conditions. The cross is itself, glory. The death of Jesus shows what is indestructible in the love of God, and the work goes on. God does not stop working, does not stop being this unselfish God because of our refusals. And so unbroken is that work, that it goes on through and beyond the death of Jesus on the cross, and is shown in the resurrection after the great Sabbath of death.

Now, almost infinitely more could be said about the gospel of John, one of the most inexhaustible texts in the whole of the bible, but I've chosen to speak about it at some length because it seems to me it is – of all the classical Christian texts – the one that most insists that faith is about seeing. It is about that double vision of myself as frightened and potentially violent and God as radiant, consistent and unceasingly creative. And that's what we're invited into in the story of the gospel; it's what we're invited into in Christian faith; recognizing the self-deception, recognizing the glory. Indeed in recognizing the glory, the radiance of an unceasing, selfless love we are somehow enabled to face more courageously and more fully our own self-deceit.

The first two things that Jesus says in St John's gospel are 'What do you want?' and 'Come and see'. There couldn't really be a better introduction to faith. 'What do you want? Do you actually want to change your life? Do you actually want human wholeness? And if you do, come and see.' So the gospel story begins not with an argument, but with an invitation, an invitation to examine yourself and an invitation to be in a place where you can see something different. ('What seest thou else?') We're invited to take time with this story, because its claim – although fairly simple – is quite a devastating one. The claim that the fourth gospel makes, indeed the whole of the Christian tradition makes, is that there is a single moment in the history of the human world where that world is completely transparent to the love that made it, where glory appears in a human face. And so, only in this light can you grasp divine love and human evasion and human violence in the one encounter.

What difference does it make? The difference that the gospel proposes, today and in every setting, is to say something like this: 'It is possible to live in a world where you can see your failure and your recurrent fears with clarity, but also to know that if you want healing, there are no conditions.' It is possible to live in a world where you can see these things. All that is, in some ways, still fairly general, but I want next to talk briefly about the states of mind, the attitudes that such a story and such an invitation suggest would be possible for human beings. I think that faith understood in this way, makes possible at least these three things. First of all, faith makes possible realism and perspective. It makes it possible for you to see yourself with, in the right sense, detachment; to see yourself not defensively and anxiously and not vainly and self-satisfiedly either, but to see yourself in all kinds of roles which are often inglorious, yet always redeemable. I see myself in faith, as somebody who fails. I see myself in faith as somebody who's loved. I see myself as somebody who is called, summoned and entrusted with responsibility, and I see myself as failing again. And I see the possibility of restoration and new beginnings. And at no point in that cycle am I allowed to see myself as an ultimate waste of space. I can see myself realistically. I don't have to pretend I'm better than I am, I don't even have to pretend I'm worse than I am. I have to recognize my limits, my nature as a growing being and as a being that makes mistakes. And the message is 'don't panic'.

Secondly, this sort of faith makes possible a way of valuing what's around you. If the world really is grounded in some unimaginable act of final unselfishness, then all that's there is gift. As you have, so everyone has, a place before the source of all things. As you have, so everyone has a root in that eternal gift. You have been given space and time to grow into intimacy with holy love, and all around you is gift. The person next to you issues from divine giving, the material environment issues from divine giving, nothing is just there, everything and everyone is given.

And the third thing that grows out of this is that, if that's true, if indeed all things somehow flow from giving, then the natural way to live as human beings in the world is in giving and receiving in a mutual intimacy. Not only intimacy with holy love at the centre of everything, but an intimacy with one another in which we are committed to making one another more human in our relations with each other. And you could say too, an intimacy with the whole world around us which allows the world to make us more human and ourselves to make the world more itself – that relationship of respect toward our environment, which seems so inaccessible for 'advanced' societies. Perspective and realism, evaluation of things as gift, a sense that we are called to committed intimacy in making each other more human, those three things which this kind of faith makes possible, stand very firmly against their opposites which I think you'll find familiar:

· against emotional infantilism - that utter lack of perspective which puts my immediate needs and the gratification of my immediate passions at the centre of everything – which can show itself as greed and irresponsibility and can equally show itself, as Jesus so often says, in censoriousness and hatred of the other.

· against exploitative selfishness, against that desire to draw the whole human and non-human environment into the great hungry stomach of my ego, or of our collective human ego, that attitude which ravages our world around us.

· and against an attitude of calculation and suspicion in human relationships.

Now, if you don't see these things around in our culture, I suspect you may not be looking very hard. It seems to me that these possibilities opened up by faith as seeing, open the door to a way of resisting some of these most deeply destructive elements of the society we're in; the global culture which all of us in one way or another in varying degrees, inhabit. And if we're talking about what difference does it make in relation to faith in public life, without spelling all this out in the details of some sort of manifesto, I would say that faith conceived in this way requires of us that kind of freedom and perspective, which actually makes change in the direction of justice, change in the direction of reconciliation, truly possible.

So far then, I've been trying to say something about the overall character of a religious commitment in our world. That character which is best expressed in terms of not only seeing but seeing that we're not seeing everything. I've tried to anchor that a bit in one of the ways in which the basic Christian story is told, perhaps the most powerful of its expressions in the New Testament, the most fully developed and resourceful. And yet you could tell the same story beginning from any of the four gospels. I tried to suggest how seeing the world as the gospel of St John invites us to see it, begins to grow in us a set of human responses to the world around which will be the material of resistance to what's most destructive in our world. But, you might well say, that's all very attractive but is there any particular reason for thinking that it's true? And that's a question which everyone has to answer for himself or herself, precisely because it's not a knockdown argument we're talking about, but an invitation we're not going to get to the point where someone standing in the pulpit of this church is going to say 'Here is the proof and any fool can see that that's how we should approach reality'. That's why I mentioned earlier the significance of both science and art in understanding faith. There's an element of risk involved in all our significant commitments. The scientist embarking on a new direction of experimentation is taking risks that will lead to a whole series of non-confirmations of a theory and perhaps finally to something that at last clicks. But this in turn will set off a new train of questions. And then when we're faced with a great work of the imagination, with the poem, film, play or novel, it's not as though the author comes to us and says 'I can prove to you that this is how reality is'. That author is saying something a lot more like Jesus at the beginning of the fourth gospel, 'Come, see. Discover what you can see by standing here'. And if by standing here it's possible to see what otherwise I can't see, I may perhaps at least begin to suspect that there is truth to be seen from this perspective where some of my old habits of ignoring things have been shattered

To come out of a production of King Lear shaken, uncertain and disturbed, is to know that I've seen something I'd rather not have seen. There's more than I thought. Is King Lear true? Well, it's not a true story about ancient Britain, but it's a true story about the world we're in. Uncomfortable because true, because it puts me in touch with things I might be a lot happier not knowing. So when that question arises 'Is all that true?' my answer is that, if by standing where Jesus invites you to stand in the gospel you see more than you would otherwise see, you see a world larger than you thought you inhabited, you have at least to ask yourself 'Is not this a reality?' and perhaps also to ask 'Am I afraid of this reality?' And if this even might be the truth, might be the grain of the real world, where do I want to put myself? What do you want? Come and see.

The story of Jesus as it's presented to us in the gospel of John and the rest of the Christian Bible, the story of Jesus is unlike any other (I say this as a Christian believer) in that it holds together, inseparably, that twofold vision I've spoken of: the overwhelming reality of divine gift, the terrifying reality of human self-deceit and fear. The story of Jesus as it's told there is not just an epiphany – a revelation of glory and no more – and it's not just a commandment or a set of instructions dropped down from heaven. It is a manifestation of radiant beauty that lands in our world in the form of a profound moral challenge, because it's a showing of active love that dissolves fear.

There are all kinds of experiences, epiphanies, manifestations of the holy. Some of you may remember that wonderful poem of Rilke's about the archaic statue. It ends with memorable lines 'There is no place where you are unseen. You have to change your life'. Now, that sense of a revelation which invites you to change, that's part of what the gospel is about, but it's even more, because the revelation is itself a revelation of an action of love into which you are invited to come, with which you are invited to cooperate. Come and see. Find if it is possible to let go of that anxious and violent self in the face of a promise of radiant beauty; to be made alive in this way. Across the human world many ways are proposed for human healing, for the restoration of humanity, but the claim of the gospel is quite simply that here in this encounter with this figure, we are brought to what the gospel itself describes as a secure and eternal place, 'in the bosom of the Father', next to the heart of all things, the place where fear becomes meaningless. And so, in thinking about what the invitation to Christian faith means, I'd say that at the very least you have to ask 'What is it that my position, my culture, my education, my status, my habits, what is it that all of those stop me seeing?' 'What does my society educate me to ignore? What does my education educate me to ignore?' And then to reflect on what might be seen in this territory around the figure of Jesus. And if it is a world larger and deeper than I imagined, without shutting out any dimension of the world, the emotions and the perceptions that belong to humanity, if it allows that comprehensive understanding of who we are and acceptance of the range, the fallibility and the promise of our humanity, then the challenge of faith is the challenge about whether we are willing to live in that larger world. A world whose truth is perhaps only fully vindicated as we discover that without it, no fully healing change happens in the world of our experience.

What do you want? Come and see. And then of course those other words so profoundly resonant in the gospel, which Jesus speaks to his friends – 'Launch out into the deep': understand that your life lies in the not knowing as well as the knowing; that your life lies in understanding your limits; that your life lies in a letting-go which allows love, reconciliation and promise and which, if you believe it aligns you with precisely that energy of creative gift which sustains the entire universe.

© Rowan Williams 2008

Questions & Answers

Several related questions dealing with Christianity and other faiths:

What possible elements might bind diverse groups – like fundamentalist Muslims or fundamentalist Christians, secular Chinese and the rest of the pluralistic world?

Should the Christian Church play a greater role in the justice system?

What is the role of missions for the future of Christianity? Should their emphasis be on social welfare or preaching the gospel?

Do you believe there is such a thing as productive inter-faith dialogue? And do you think that only through accepting the claim of the gospels in Jesus will we be able to fully realize perspective, giving and intimacy, or do you think there are other ways to come to these understandings?

Archbishop:

Let me take the last two of those to start with. 'Is there such a thing as productive inter-faith dialogue?' Well, the short answer is yes. I've experienced it many times with Jews, Muslims, Buddhists particularly, and with some others too. And what I define as productive inter-faith dialogue is not an attempt to negotiate a position that nobody recognizes as their own, but to understand where each person's coming from, to be open to the possibility that you might emerge from the dialogue knowing more about God than when you started. This doesn't mean being converted to the other person's point of view, necessarily. And I believe also that good inter-faith dialogue helps you clarify a bit the possibilities and limits of action together in our society. This is related to one of the other questions: 'What possible elements might bind groups together?'

Now the examples there are of what might bind fundamentalist Muslims, fundamentalist Christians and secular Chinese and the rest of the world ... I'm afraid I haven't got a short set of answers that will solve that one. (That means my chances of the Nobel Peace Prize are much reduced!) But let me say this: in what is now several years of experience of dialogue with both Jews and Muslims in fairly intense and sustained ways, I've come to believe not that we have x, y and z in common and a, b and c that divide us; I've come to realize we do start from very different places, and we end in very different places and yet there is behind all of it a very strong sense that we see human beings in a comparable way. We see human beings as capable of receiving the will of God as an imperative and a possibility, human beings as given responsibility, and that's quite something. We don't see the process of that revelation in the same way. We don't see the precise demands upon us in the same way. And yet we have some sense of a human dignity, which I think is not trivial. And do I think that is only through accepting the claims of the gospels? Well, I suppose, finally, the reason why I'm a Christian is that I believe that it is in that relationship that human beings will most fully come to what God purposes for them. That's why I'm a Christian. Does God regard himself as bound by that? That's for God to say. Are there evidences of lives of creativity, holiness and excellence outside the boundaries of the Christian Church? Yes, don't let's delude ourselves about that. Does that mean that the grace and gift of God is around in places where I hadn't expected to see it? Yes, of course it does. Jesus had quite a bit to say about Samaritans in his own day, and some of what Jews said about Samaritans, and what some Christians say about Muslims these days no doubt, are not all that different. And yet, I can't get away from the fact that the gospel lays before me what I regard as a coherent, and credible and compelling vision of human beings becoming human in that relationship with Jesus. That's what I believe I've been given and what I must witness to. And what God is doing outside that relationship – I'm not God – I leave to him.

Should the Christian Church play a greater role in the justice system?

One of the things I was trying to say, a couple of weeks ago, is that a good society is one which understands that people have lots of overlapping allegiances. While everybody may be a subject of the law of the land, that's not the only thing about them. The law of the land when it's working well, is working with, not against those commitments and loyalties which, as a matter of fact, hold people together. These are sometimes as strong as religious law, and sometimes are just a matter of association and habit. So, I would like to see in a well-functioning society a universal law that – as I think I said in the lecture a couple of weeks ago - guarantees fundamental liberties for absolutely everybody with access for absolutely everybody. But one that is prepared to ask where conscientious exceptions should be made, where local custom or religious methods of conflict resolution might be supported by the law of the land ...and I think that does apply to Christian culture and law and morals, as to Islamic.

What is the role of missions for the future of Christianity? Should their emphasis be on social welfare or preaching the gospel?

Both! Because preaching the gospel is preaching, proclaiming that human beings are immeasurably worthwhile in God's eyes. They are so worthwhile that the life of God in the flesh, the life of Christ, is poured out for the sake of everybody. God so loved the world that that he gave his only son says the fourth gospel. In other words, preaching the gospel is saying that human beings are more worthwhile than you could ever begin to imagine. And if that's the case, the social implications and the political implications are immense. Most of our world is not organized on the basis that human beings are massively worthwhile. The Archbishop of York and I spent a couple of hours this afternoon in a detention centre in Oakington, and that is why I want to say rather strongly this evening that quite a bit of our society and our world is not organized on the basic vision that human beings are infinitely worthwhile.

If you decide to ignore parts of the Bible which clash with modern ideas of equality and human rights, do you undermine its primacy and part of Christian belief? Does this mean that you believe that some parts of the Bible are not divinely inspired?

I don't think we ought to ignore any parts of the Bible, and I certainly don't think that modern ideas of equality and human rights are God-given and obvious. How we read the Bible's vision of human rights and responsibilities in our contemporary social context is always a bit of a challenge, and it's shifted a bit across the centuries. To take the obvious example: it took us quite a while as Christians to notice that slavery didn't sit very easily alongside the gospel. But I don't think that for all those centuries Christians were being biblical, and then suddenly acquired a notion of equality and human rights that taught them slavery was wrong. I think they just started reading their Bibles a bit more carefully. And so I don't think there is that absolute opposition (I think I see where the question's coming from) I don't think we simply ought to take slogans about equality in the modern sense, as obvious and unarguable. We need to bring them face to face with what scripture says. But be prepared to be surprised by what scripture says.

Genuine faith is openness to more than we have yet seen or known. How do you marry this with a New Testament called to guard the deposit of faith? How do exploration and authority stand together – or can they?

The deposit of faith in the New Testament is, I think, first and foremost the memory of Jesus and the witness to the fact that he is contemporary. That is, the memory of the mystery of the cross, the witness to his resurrection. That's what has to be guarded, transmitted, and made real in life after life after life, generation after generation after generation. And because St John says that the whole world could not contain all the books that could be written about Jesus: I take it that the New Testament also says that in that process of passing on the memory of Jesus and the witness of the resurrection, there will be more and more to discover, more depths. There is a great eighteenth-century Welsh hymn which speaks of the mystery of God as 'a sea to swim in, not to cross over'. That will do for me.

How do we as Christians effectively show this loving vision to the world?

Well, how long have you got! I can tell you how we don't. We don't show that loving vision by presenting an image of people who are constantly monitoring one another with such hostile anxiety that other people can't see in us a fundamental gratitude and generosity. And from age to age the Church has, sadly, got stuck in that anxious monitoring of one another so that we may not quite know where we are, but we're absolutely sure where they are. And the famous story of the old Scots lady, who decided to found her own church, comes to mind. The local Presbyterian minister came to visit her and says 'Are you quite sure that only you and your coachman are going to heaven?' (This was the only membership the church had got.) The old lady thought for a while and said 'Well, I'm not so sure about Jock...' That's one way we don't do it! I think the way we most effectively show loving vision, is by going on behaving as if change for the better were possible, as if it were not a fiction or a fantasy to think that peace and justice and reconciliation could happen.

Who are the people that the world looks to as hopeful signs of our time?

Well, I may be prejudiced as an Anglican, but I do think that Desmond Tutu is pretty well up on most people's list ... and why is that? It's partly because he shows that change in the direction of justice, reconciliation and forgiveness actually are not fantasies. That's a good place to start, I think.

In the sense that science can help us master the world, is it, in your words a form of 'terrible religion'?

Actually, yes ... I think that a scientific world view which says that the purpose of science is the exhaustive mastery of our environment is both bad science and bad religion. It's a form of religion. It starts with a massive world-conquering confidence that it can wrestle human limitation to the ground. I don't think that's a particularly good place for science to be, and most serious scientists wouldn't want to go there. It's certainly a form of bad religion. 'Mastery' is a very double-edged word. The mastery of our circumstances, meaning it helps us to have some control over the circumstances in which we live, so that we're not passive and helpless, OK. Mastery in the sense of containing and enslaving the environment we're in - so that we are never surprised by it and never at a loss in the face of it – I think there's something deeply inhuman about that and deeply unreal.

Modern Western society doesn't as a corporate body recognize its need for God. It does however seem to acknowledge a great deal of boredom and restlessness. In what ways do you think the Gospel can offer a compelling response to the modern experience of boredom?

When I preach sermons to young confirmation candidates I do sometimes, I'm afraid, say 'Sooner or later somebody is going to have to let you into the terrible secret: church can be boring. Get used to it.' A degree of boredom is part of your humanity; don't expect that being human is being constantly entertained. Putting that on one side ...though it's a warning worth heeding... I sense in the great saints of the Church, the really great Christians that you come across from time to time, that they are capable of what the spiritual tradition calls the Practice of the Presence of God or the Sacrament of the Present Moment. That moment by moment you are aware of yourself and your surroundings as somehow shot through with gift, with generosity, and moment by moment you just open yourself to that reality. And that doesn't mean you're in a constant state of ecstasy, it simply means that what's before you is itself. God's gift, God's being somehow radiates in it and you move from moment to moment with a sense of welcome. What else can one say–a sense of welcome; and maybe that overcomes boredom? But how to get that across as a sort of cultural programme, I'm not at all sure.

Do you have any thoughts about the way in which climate change and its connection with the movement of Western civilization may affect the way which religion has historically conceived of human beings in the world?

A very good question and I think already we're seeing in the world of religious faith, especially Christian faith, a degree of embarrassment about the way in which bad religion has prevailed to such an extent that we have been seduced into thinking that the world's there to be squeezed and used by us and no more. I think that over the last forty to fifty years gradually the emphasis has begun to shift for a lot of religious people and I think it will shift still more and it needs to. We need to be back in touch with that dimension of religious commitment which, as I said just now, looks at our environment with a spirit of welcome. Not 'What can I get out of this?' but 'What's the gift I need to receive from this person or this bit of the environment just being the way it is'. 'What can I receive from that?'

What do the gospels teach about homosexuality, is it an affliction to be healed?

Is sharia law a product of terrible religion?

Two very simple and very tough questions. Neither the gospels nor the New Testament as a whole have a teaching about homosexuality as an orientation as far as I can see. In the gospels Jesus is very clear about certain kinds of sexual behaviour being inadmissible for his followers. He doesn't mention homosexuality specifically, though he may take it for granted. St Paul at the beginning of Romans famously has quite a bit to say about the perversion of what he calls natural heterosexual desire into homosexual desire and regards the practice of that desire as a sign of human failure. The question with which the Church is wrestling at the moment is how to map all that onto people's experience and understanding today of homosexual orientation and behaviour. I'm not one of those who think you just tear up what the Bible says and move on. Equally I'm not convinced that we fully understand how to put those things together. And that of course is why the Anglican Church is in such a muddle over this at the moment, and if I knew how to cut the Gordian knot overnight, once again, I'd be very glad of a quick solution. I can only say that that's where we are. And I don't think that the Bible gives us much ground for simply regarding homosexual orientation as an affliction to be healed. It says quite a lot of other things about homosexual behaviour, St Paul takes it for granted that it's sinful but you don't get much about the orientation as such.

As for sharia law – it is a very, very wide-ranging scheme of legal understanding within historic Islam. It's rooted in the sense of doing God's will in the ordinary things of life. In some of the ways in which it's been codified and practiced across the world, it has been appalling. And in some of the ways in which it is practiced now in terms of the punishments inflicted and the attitudes to women encoded in places like Saudi Arabia, it's grim. But, to judge Sharia in its entirety by that, is really rather like judging the Bible by a couple of chapters on the genocide of the Canaanites, let's say, from the Old Testament. We need a bit of perspective on this, and my doomed enterprise the other day was trying to produce a bit of perspective ... let that be a warning to you all!

Can you unpack a bit more the way in which art can aid the life of faith?

I suppose I'm slightly prejudiced in that I find the arts one of the most enriching things about my faith. It's one of the things that feeds my faith: drama, the visual arts and perhaps particularly poetry. And art feeds the life of faith when it keeps alive that sense of the unseen depth of things: whether it's the depth of human relations and emotions in drama and fiction or the depth of the visual world in the visual arts. That sense that there's always more to it ... I think the phrase I used a few years ago writing about this, was that the religious dimension of art isrecognizing that everything is more than it is; gives more than it has; has a resource, a dimension to it that we don't otherwise see. Understanding something about the world of art just habituates us to living in a world which is strange, not a world that's capturable and containable, and I think that's good for us as people of faith.

Is faith the fruit of our desire or renunciation?

Well, the fascinating thing I suppose is that faith is both the end of all our desiring, it's where all our deepest longings and emotions are converging, and at the same time we're told that when you get to that point of deepest convergence you can expect it to be like nothing you've ever imagined–renunciation. So, I'm afraid it's a very Anglican answer, both. We can't understand faith at all unless we understand that it is about desire. It's about Eros, about longing, about the yearning for beauty, love, relation, intimacy and you can't read a word of any religious text without seeing that. And yet, and yet the worst thing that can happen to us, it's sometimes said, is to get our heart's desire, as if I were to write what would make me happy, fill in the form, hand it in to the holy and mysterious, and holy and mysterious instead of being holy and mysterious, said to me 'OK, you can have exactly what you want. No more, no less'. And what I would miss out on was all that I hadn't known I wanted, all that I'd never known I desired. It's why, if you'll forgive the analogy, computer dating is a bad analogy for faith! We need to be surprised, and if we want to be surprised we need to do a bit of renunciation, letting go of our attempt to master the future. It's the old ego again, trying to get on top of things and renouncing that and saying 'OK, I have to let go of what I think I want from God, what I think I want God to be like: I'd better let God be God.' Every serious Christian writer, I think, has taken that for granted and spelled it out, and it's what the great masters and mistresses of contemplation are always talking about.

You spoke of the difficulties of ego. Is there a particularly hard battle to be fought in this respect, surrounded by the ceremony and importance of your office?

Many years ago when I was fairly newly ordained, I remember taking part in a ceremony – I think it was a wedding – in Norwich Cathedral. Dressed up a bit and going in procession to the Cathedral to take the service, we passed some tourists peering at us round a pillar. And I suddenly had this awful revelation of how utterly absurd it must all look! Quite seriously, unless you retain at least some sense of the absolute ridiculousness of it, you're missing out. Because, here we are, a Church with a long history and intellectual sophistication of sorts and lots of treasures both literal and metaphorical, telling the world about poverty and openness of heart and all the rest of it ... Here we are, an established Church talking about a rejected, powerless, crucified Saviour ... And the reason for carrying on with the Church is not that it looks serious and compelling and earnest all the time, but that whatever else happens it still retains from age to age the saving grace of repentance, which is another way of saying it sees itself as stupid. I said a couple of years ago that rather than saying the Church is one holy, catholic and apostolic, we should say the Church is one holy, catholic, apostolic and repentant. Because when the Church turns on itself that perspective of realism, then it must know what it is not doing, witnessing and achieving. And we just have to keep that alive as individuals, not just Archbishops, as a Church corporately, otherwise we are sunk.

Thank you.

© Rowan Williams 2008