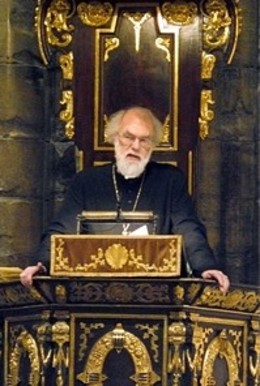

Archbishop's Holy Week Lecture: Faith & Politics

Tuesday 18th March 2008

A lecture given by The Archbishop of Canterbury in Westminster Abbey during Holy Week 2008 - the second in a series entitled 'A Question on Faith'.Click downloads on the right to listen to the lecture [44Mb], and the question & answer session that followed the lecture [23Mb].

Read the transcript of the lecture below, followed by the questions & answers - or click here to go directly to the Q & A transcript.

Transcript of the lecture:

Faith & Politics

Yesterday evening, looking at the supposed conflict between faith and science, I suggested as a conclusion that scientific research and enquiry was one set of practices among many in the human world: no more good or evil in itself than anything else. Its moral compass was not derived from itself but from all kinds of factors in the culture around. But all of that should encourage us in thinking that the Church and other religious bodies has every reason for supporting and encouraging scientific research, and no great reason to panic, whatever anybody might say. But if we're thinking about science as one practice among many in the human world, and if we're acknowledging that scientific work doesn't generate its own moral compass, then we have to face a number of issues around how society itself shapes its moral vision and its sense of what's distinctive about humanity. In other words, as you think through some of the issues around faith and science, you're more or less bound to get into questions about faith and the public realm: faith and politics.

This is a building in which the National Anthem is sung fairly frequently. But the historic second verse of the National Anthem is probably sung rather less frequently than the first, or the revised version of the second verse. For those of you who don't habitually sing the original second verse, I may need to remind you that part of it runs 'confound their politics, / frustrate their knavish tricks'. The rhyme tells you all you need to know about what the author believed about politics. Politics has, in the history of the English language, a rather bad name as a term. Shakespeare in King Lear refers famously to 'scurvy politicians' who pretend to see the things they do not. Politics and politicians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not respectable activities or agents: they were plotters, manipulators. And 'politics' in that period of the English language had a very negative connotation for that reason. Even rather later on and outside Britain, you find the great French poet Charles Peguy saying about a century ago that everything begins with mystique and ends with politique. All human visions, it seems, begin with something transcendent, something luminously obscure and suggestive, and they all end in committee rooms. Politics carries with it that abiding sense of a corrupting or corrupted milieu: the language of faith ought not to be mixed in with the necessarily ambiguous and sometimes corrupt business of getting your way in the public world.

One of my tasks this evening will be an attempt to rescue the word 'politics'. In its most ancient use, as it's used by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, for example, as the title of one of his great works, politics is simply the discipline, of how to think about civic life intelligently and consistently, and how to manage civic life in a rational and just way. Politics is the science of living together without conflict or major injustice. And in that sense you can perhaps see how a rather different meaning just might be given to the words of the French poet. Yes, everything begins in mystique, begins in vision, and needs to be translated into the science of human living together; and in that sense also, politics is inescapable for anyone in or out of the Church or any other religious community. And the Christian Church is itself a political community: it's about living together in justice. Now that is no fashionable modern discovery, it's already taken for granted in Christian scripture. The early Church saw itself as a body of citizens: you'll find the language in the New Testament, famously in Paul's letter to the Philippians: 'your citizenship is in heaven' says Paul, using the Greek word politeia. The city you belong to is something other than the community you think you belong to here on earth. You are still social beings who have to make choices about living together, but the community to which you belong is greater than any limited human society.

The politeia, the citizenship of the Church is to do – like other kinds of citizenship – with how people take responsibility for the management of power, how they cooperate, how they become responsible to each other. And the Christian community talks about itself as a polity, a kind of civic life which is in some way transparent to God. It builds on the whole history of God's dealings with the people of Israel in the days of the first Covenant. God deals with the world it seems, in biblical terms, not by individual revelations or even by generalized messages from heaven. God deals with the world by bringing into existence a community living by law, aspiring to justice, and in its dealings within itself, the dealings between people, somehow showing transparency to God. Ideally, somebody looking at ancient Israel would have been able to work out the kind of God it believed in. And the same applies, in the mind of St Paul and other early Christian thinkers, to the Church. 'Look at the Church and you may begin to see what kind of God is being talked about when you see how people relate to each other.'

It's not only in the New Testament that you find that political language and imagery around. As has very often been pointed out, the very word for Church in Greek, ekklesia, meant 'a citizen's assembly' in the ancient world. And so in the earliest Christian period, to become an adopted child of God in Jesus Christ, was simultaneously to become a political being, in a new way: to become a citizen of a larger society. To receive the grace of God, God's mercy transfiguring and enlarging your life, was, at one and the same time, to take on responsibility within the City of God, to take on responsibility for common life. St Paul picks up one of the current metaphors in ancient philosophy for society: the metaphor of the body. He didn't invent it as a metaphor, but he does some very distinct and new things with it. Instead of just saying that everybody has a different job in society, Paul says everybody has a different form of service in society, and what is given to any one member of this society is given for the good of all and requires a letting-go of selfish interest. Mutuality and self-giving belong properly to this citizenship, and all kinds of power in this citizenship are there as a capacity to be put at the service of common life. So instead of the slightly static picture of the body as it appeared in ancient philosophy—that is, a society where lots of people had different jobs which more or less inter-locked—Paul gives a dynamic focus to the language. The body is an organism where life flows between different parts, where service occurs on the part of each to all and all to each.

Now that means that the politics of the Church and the political critique and questioning which the Church may raise, is never going to be an abstract scheme or programme, it's going to be a set of critical touchstones. 'Here' says the Church 'is a pattern of social life which we believe to be transparent to God.' How do the practices of this particular society measure up to that transparency? What do they hide about God and about humanity? Buried in that, of course, is a very ambitious and unlikely claim indeed, that the Church is the ideal society. Ambitious and unlikely, because five minutes' reflection (or possibly even less) may persuade you that this is some way from what the Church has looked like and does look like. And yet, in the perspective of the New Testament, that is precisely the claim made: the sorts of responsibility, the sorts of priority, and the sorts of mutuality that exist in this body are what God purposes for the human race. And in examining the way in which this community works, you ought to be able to understand what real justice might mean.

Among the many mistakes the Church has made, historically, in coming to terms with this, is the assumption that - sometimes and in some places – this gives the Church license to set the agenda for everybody in sight; to set it in coercive and often oppressive ways. But, as the Church has very, very, slowly persuaded itself on some subjects like freedom of conscience, it has come to realize rather more sharply that if it is itself the body of those who freely consent to a common allegiance, it can't commit itself to coercive institutional forms, whether visible hierarchy with absolute powers or any particular form of state administration. It always remains what the great English poet Coleridge called 'a critical friend', in the political sphere. It doesn't seek to set an agenda by imposing or controlling; it proposes not abstract criteria for morality, but simply what it itself is. It proposes to the society around that these forms of mutual care and service and accountability are the forms transparent to the most fundamental reality of all: that is to God.

So, there is no way in which a Church can be indifferent to politics if politics is understood as that science of understanding and managing with justice the way human beings live together. And because of all that, the Church proposes to the society around certain roles and images and concepts to do with humanity. It's a community that grounds its practice on the conviction that human beings are created: that is, they are responding beings before they are initiating beings. They exist because God wills them to be. Human beings are invited and enabled to respond and to be responsible to God and to one another. Humanity rests on that responsiveness. And because all are created and all are equally the subject of God's invitation, whether or not they accept it, the first and most important thing you know in practice about another human being is that God has invited them to exist and invites them to exist in greater fullness.

For the Church, as for other faith communities, belief about humanity is absolutely bound up with belief about God and vice versa. So within a variety of human societies there exists a body of people whose view of what humanity is about is shaped radically by belief in God – an 'inviting' God, to whom response is required – whose view of humanity is formed by the supposed attitudes of God to us, the promise of restoration – a new beginning, of mercy and new creation. Within every human society, that is going to be a presence, an element. Historically, it's very often been a dominant or majority presence: in many parts of the world it still is so. But in our North Atlantic world as presently constituted, it would be rather hard to claim that that was a dominant view. Nonetheless, there it is, shaping the vision and priorities of certain people. And the question of the relation between faith and politics therefore comes to be tightly connected with the question of how such a group of people manage their relationship with a dominant cultural environment which doesn't have that doctrine of human nature, and perhaps doesn't have any doctrine of human nature. How does the Church relate to that secular environment? With what degree of confidence, humility, aggressiveness, hopefulness? Before moving on, I would just like to mention one observation, a quotation from Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanzi, Archbishop of Milan, who at a conference in Lyon some three or four years ago said: 'the human recognition of God's existence is not a compliment paid by humanity to God, but a gift given by God to humanity'. That, I think, sums up rather more elegantly than I can a great deal of what I've been trying to suggest in these opening thoughts.

So, what happens when we find ourselves as a believing community in the middle of a wider society that doesn't quite know what it believes about human nature or human distinctiveness? One of the tasks which lies before us is perhaps to attempt to draw out a bit more fully, what those around us do take for granted, if anything. I mentioned in the first lecture the way in which the issue of creating human embryos strictly for research purposes raised a number of broader questions about where we regarded the limits of human dignity to lie. But there are others in our society who, in different ways, would regard what is human as in some sense, up for negotiation or recreation. There is a movement rejoicing in the name of the Extropians who believe that the ideal future for humanity is cyberspace, and that the limitations of the body are more and more being eroded by the possibilities of electronic cyber-relationship, and that that is where we should put our energy and where we should hope to find the human future. If what I said about the Church earlier on is both ambitious and unlikely, you may feel it's not the only project to which those adjectives can be ascribed!

But what I'm saying is that in our public debate, we need to draw out a little bit further whether there is in any of this a doctrine about humanity. And very often the doctrine that emerges is a doctrine about human will and human choice, a doctrine which assumes that human will and human choice can, in certain circumstances, override any sense of the givenness of a human nature, an embodied human nature. Now, that's to oversimplify it radically, but it does seem that drawing out the doctrinal tension between a view that gives priority to will and choice, and a view that believes that something even if we're not quite sure what, is given about human nature and human dignity, invites some very serious and far-reaching debate. And just as, in the case of some of the scientific controversies I spoke about last night, we are sometimes fighting in the dark with those who don't fully recognize that they are espousing doctrines, one needs to draw out such assumptions so that there can be an open exchange. The problem arises when some people imagine that their account of human nature, or their understanding of human will and choice, is so rationally self-evident that it doesn't need to be drawn out, argued or defended. But it's of the first importance to recognize that a great deal of what is said in our current debates, whether about the status of the embryo, the character of the human body, or whatever, involves matters of faith – belief that dignity belongs here and not here, that these are the limits of what is given about humanity.

But you may say that's only one aspect of our contemporary human culture, and not the most positive. What about the fact that we live now in an environment very much dominated by the culture of human rights? Surely that secures for everyone in society, a clear sense of what is non-negotiable about humanity, a clear vision of a human dignity that can't be adjusted to convenience? The first thing I want to say about that is that it is crucial that the Church should be positive about human rights. The culture of human rights has made it harder to see human dignity as negotiable; harder to see human dignity as the possession of some rather than others. There is a thoroughly welcome universalism about this approach. It's no accident that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights entitles itself in that way as a matter of promise to all human subjects, wherever they may be. And yet, there remain some difficulties here. The history of the twentieth century, including the late twentieth century after the acceptance of a Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the UN, is not a history that encourages you to think that universal acceptance of human dignity is beyond question. In addition to countless wars, in addition to the development of weapons of mass destruction, we now also have the reopening of the question of whether torture is ever permissible. This is a question which many believed could no longer be raised some twenty years ago. Those remaining uneven areas of our rights culture should at least make us wonder whether the foundations on which it was laid were sufficiently secure. What's more, the human rights culture as it has developed in a competitive, increasingly globalized, boundary-free environment where historic communities are fragmenting is a culture that has rather encouraged the sense that the most important thing about any human individual is that he or she has claims which somebody is able to enforce. And that, while an essential part of a human rights culture within a law-governed society, is of itself a rather slender basis for the understanding of human dignity.

Within this environment - an environment which in some ways seems very uncertain about the limits of human dignity, which in other ways has some hopeful signs in terms of human rights and yet a lot of unfinished business – where does the Church stand and what is the priority with which it works.? The first thing I'd want to say is that if we're speaking of rights, the Christian community and the Christian individual need to stand on their right to attempt to persuade – not a right to settle questions by fiat: not a right to impose conclusions; but a right to participate in public debate and try to convince.

About eighteen months ago, when issues around the legalization of assisted dying were very much in public debate, some said with feeling and anger, 'by what right does the Church or any other religious body seek to impose its understanding on others, to block the freedom of others to do what they choose?' And the answer which I tried to give then and which I'd still give now, is that the Church has no right to block the freedom of others and no right to dictate its philosophy, but it has a right to attempt to persuade a voting public, whether in the general public or in the slightly more rarefied atmosphere of the House of Lords. I don't believe that there is any insult to the freedoms of others implied in that invitation to debate, and if the Church or the individual fails to persuade and the vote goes the other way: what then? Then, the Christian individual and community have the same freedom as anyone else to seek to change the law, to persuade once again. And what if the law imposes upon the Christian duties, obligations that are in conflict with conscience? Then of course there arises a very difficult problem. Christians have historically held to the right to resist what is believed to be directly against God's justice: to disobey, to fail to obey a command - even from a legally appointed superior – which is in conscience held to be against God's justice. That is a liberty the Church has always recognized, and a liberty which most liberal states likewise recognize because of their valuation of conscience. When abortion was legalized in this country, provision was made for the consciences of some. And if society doesn't grant this, then the conscientious believer has to be prepared for the possibility of suffering for conscience. None of that is new. It's ingrained in that long-standing tension between the community, the citizenship that is brought into existence by the act of God in Jesus Christ for the Christian believer, and the citizenship which belongs to the Christian in virtue of being here or there at this particular time. It is that inescapable area of reserve which makes the Christian always a slightly suspect figure in a society that is looking for unconditional loyalty to anything and everything it may determine. And I have to remind you that during the twentieth century it has been of the first importance that there have been Christians who have lived out of that sense of liberty and reserve, and so have challenged the worst tyrannies of our time.

If there really is a right to persuade, or at least to try to persuade, that means also what might be called a 'right to be visible' – an assumption that we still live in a society, which, however secular its processes, is still open to the raising of fundamental questions. From the religious viewpoint a healthy society is one that in order to foster such debate is not afraid of the public acknowledgement of and engagement with communities of religious conviction. It's precisely what is encoded in the existence of 'faith schools' as they are now so unhelpfully called. The state decides that it can and should engage with communities of religious conviction, negotiating what it can do together, insisting on its own legal state supremacy and yet negotiating with communities of conviction for the expression and dissemination of their own views. That is a healthy society. To the extent that we enjoy all of that, in this country, we live in a healthy society. And one of the signs of slight risk to our social health is the rising presence in our society of some unease about this: an unease about faith schools; an unease sometimes expressed about whether it is right for people who have certain convictions to play a part in government. Against this, we can only say that the risks of a polity which overrules conscience or which seeks to ignore communities of conviction in the public sphere are very high. The coercion of conscience is never a pretty sight and the exclusion, whether de facto or de jure, of people with certain convictions from public office is again something for which the precedents are not particularly happy. But the paradox is, I would say, that in a healthy society both the believer and the secularist may find themselves facilitating and defending the conscience of the other. A healthy society is one in which the believer is prepared to stand up for the conscience of the secularist as much as the secularist for the conscience of the believer. Once again, I believe that is where we largely find ourselves today in this country: to the extent that this comes under question or criticism, we need to have the argument.

Now, all of this takes it for granted that our moral perspectives as human beings, when they are clear and coherent, derive from what some anthropologists like to call the 'thick' textures of common life – that's to say from a common life that is many-layered, culturally alive and creative. Our moral perspectives don't just derive from abstract civic principles. Which is why a culture of human rights, without a context in practices of respect, of traditions of behaviour and so on, can lead to a deeply individualist atmosphere with a lot of anxiety about litigation and enforcement. And again you won't need me to underline that there are aspects of our society driving in that direction. A society that is only about individual rights and publicly enforceable contracts is going to be a thin phenomenon. It's going to be socially and morally anaemic, and its capacity for positive and creative mutual respect for the imagination of the other's reality is going to be very diminished. That's why it is very hard to legislate a neighbourhood into existence; why it's hard to create a corporate identity out of nothing; why it's extremely difficult to define and legislate for what we might mean by 'Britishness'; why it's very difficult to sustain commercial life without a solid background of practices of mutual trust, and so on. A healthy society is one where the culture of human rights rests upon, is informed by and sometimes challenged by the many-layered, interactive texture of a society aware of its past, aware of identities and commitments that are more than just those of public, enforceable contracts.

Once again, to speak of this Abbey where we're meeting: this is the place where monarchs are crowned and whether you are a monarchist or a republican or not too sure where you stand on the spectrum between, you will at least, I hope, recognize that there is a very large question of what it is in any society that holds together a body of practice and tradition which can outlive any one political practice or party. And it's that wider context - not simply of civil society, but of communities, of conviction and commitment – that wider reality, in which I believe the Church along with other religious communities has a distinctive place in shaping how a society thinks about itself, its health, the right and wrong ways of change.

So, moving to a conclusion: as I hinted at the beginning I'm proposing this evening that rather like science, politics needs to see itself as one set of practices which human beings are involved in. To take yet another aphorism in which the word appears: everything is politics, but politics is not everything. When politics seeks to be everything - politics in the sense of pure management of our life together, without history, corporate identity or tradition – it becomes what the National Anthem describes as knavish. And the consequences for politicians are just as serious. When politicians are understood to be first and foremost a professional, political class without a human or cultural hinterland, without connection with communities of conviction, when the only thing we need to know about politicians is their absolute neutrality with respect to any of the specific communities that make up real societies, I think we end up not only with anaemic politics but anaemic politicians. The great historian of German culture, Nicholas Boyle of Cambridge, has spoken of the immense significance in European history of that nineteenth-century process by which, especially in Germany, a class of professional politicians was created. If politics is too important to leave to politicians, I think I'd like also to suggest that politicians are too important to leave to politics. I would like to see a situation in which our communities of conviction, particularly our religious communities, actively encouraged their members much more to enter into political life and responsibility, simply so that we should go on having three-dimensional persons in public life. Politicians deserve better than to be abandoned to pure politics.

So, political identity, the understanding and management of life together, is an inseparable and necessary part of the identity of a Christian. And a Christian brings that dimension of politics to the understanding and management of political life around him or her. Christian discipleship is formed by that sense of responsibility to God and the other, and the need to create a form of life together that is transparent to the justice of God. And that vision, more than any set of principles, or system of morality, that vision of life together is what the Christian proposes in society. It may or may not be accepted, but healthy society accepts the need for a critical friend, able to stimulate and sustain debate about human dignity, its reality and its limits. Without that, our politics and politicians are in danger of becoming bloodless. But to raise those questions is to press a little bit closer to the issue I hope to be reflecting on tomorrow night: what are the roots, the bases from which Christian conviction grows? How does the Christian polity, the Christian citizenship arise historically? And on what grounds might we take that process of its arising seriously enough to believe still that it has a place in our society and our intellectual horizons today?

© Rowan Williams 2008

Questions and Answers following the lecture:

Could you suggest one thing that we as individuals could do to help build a better relationship and dialogue with the Government politic? What would that be?

There's a little cluster of things that I think Christians in particular might very well like to reflect on. One is very simply praying for your MP, building a relationship with your MP, and trying to make sure that local MPs do get invited to engage with the local Christian community wherever you are. And at Election time Churches are remarkably well-placed, in my experience, to organize hustings for candidates. I think at both the last Elections, there was very good evidence for saying that where the Church had organized public hearings for candidates in public office, they had been better attended than in any other context, by a very substantial factor. That's something worth thinking about if you want to get engaged in a good mutual debate.

Do you think that sometimes it's possible for the political realm to prophesy to the Church, and other religious institutions when they fall short of their calling?

Yes, I do I think that in the history of Western Europe there have been moments when the wider society has called the Church to account for not following its own truest instincts, and I've often used the analogy of the Church itself having lit a very long fuse which trails outside the boundaries of the Church and explodes sometimes in the face of the Church itself. Society brings back to the Church its own deepest convictions and says 'isn't this what you meant?' I like to think that the history of Feminism has been a bit like that (that might take me on quite a long excursus) but I do think that it's often been the ambient society that has taken more to heart some of what the Bible has said about the rights of women, than the Church has.

Does Christian resistance to what goes against God's justice amount to rushing to God's help in his divine weakness? Doesn't this make Christians appear much more powerful than their God seemingly is?

There's a very profound theological insight in that question. And that's why I don't think, as a matter of fact, Christians ought to 'rush to God's assistance' as if God needed our help to maintain his cause or his justice. I do think though that that's rather different from the Christian claiming the liberty not to obey a law which in conscience is believed to be unjust, because that may bring the Christian into just the marginality and the vulnerability which is where God meets us in the Cross. Recently, for a variety of reasons, I re-read a play by Charles Williams -- the Anglican novelist, poet and critic of the nineteen twenties and thirties – on my predecessor Thomas Cranmer. At one point one of the figures who represents a particular form of religious extremism in the play says to Cranmer something like; 'how is God going to be safe if we stop killing?' Now that's what over the centuries, a good many Christians have taken for granted. That, I think is a chilling, appalling, almost blasphemous observation, and that's not what I mean by the Christian claiming certain rights of dissent.

Was Jesus a-political?

No, I don't think he was. Jesus was certainly in no sense a partisan in the politics of his day, but it's perfectly clear from the Gospels that what he intended to do was to establish a community, a people, an 'Israel', a community in which God was reflected (or not) in the way in which people related to one another. And that's why the Church begins with Jesus, not with St Paul, because Jesus deals with the exclusion from community that affected the sick or the unclean. His miracles of healing for example are very often to bring the excluded within. And so I don't think you could say he was a-political. He was constantly being nudged and shunted into position by those who wished him to take their side in a political conflict, but he evades those pressures. He evades them not by taking refuge in an internal world of spirituality, but by acting to re-create community in his own terms.

Do the rights of the few or the rights of the many predominate, if the use of torture is in order to prevent a terrorist attack?

I would have to say that there are some things which when we do them, so alter the moral character of our own position, that we only do them at the cost of undermining everything that we stand for. That's why I believe that even in such circumstances, torture is inadmissible. It's never been a successful way of getting reliable information to put it mildly; it's not as if you've got a cast-iron case for its efficiency. But even if you had, I would say (as I would have to say about nuclear weapons) there are some things the use of which represents an abandonment of our own moral claims. That's why I think we mustn't give in.

The human right to influence can become control: fundamentalisms, atheism, Christian, Muslim, Jewish politics and religion. Comment.

Influence can become control, yes. Which is why everybody, religious or otherwise, claiming the right to persuade (and I would underline 'persuade' rather than 'influence' which is a more nebulous and perhaps more dangerous word) needs at the same time to have a very robust doctrine of legitimate dissent. That's why I said the believer needs to be active for the sake of the conscience of the unbeliever, just as much as the other way around. I think if that is so, if the priority of ongoing disagreement is accepted, then the claim to a right to persuade is proper. What I mean by that is that if you win the argument on some controversial matter, that doesn't give you the right to stop the argument for ever, you can't close it off. Winning any argument in political terms is a short-term thing: it's worth trying when you care deeply about the issues involved, but you can't, if you win, close it off and assume you now have the right/mandate to allow no further change. While I think the Christian Church, like other bodies, needs to have some scepticism about one form of democracy applicable to absolutely everybody, everywhere, there is an element of democracy, the simple right of disagreement, which the Church does need to defend.

If politics is the science of living together with justice and the Church is involved in that, why has not more effort been made by the Church to oppose the abolition of the Blasphemy law, when blasphemy as Leslie Newbiggin said 'is the poisoning of the well-springs of social survival and justice?

A very current question ... I wasn't able to be in the Lords for the debate on the Blasphemy amendment, but I was able to say something about it a couple of weeks before in the Lords. And the problem that I think many Christians felt in conscience about this was that the Blasphemy law had been used consistently only in circumstances where social disorder was involved, not as a matter of ideological principle, for a long, long time, and that suggested it had become a 'dead letter'. The point that the Archbishop of York and myself made in writing to the Prime Minister about it was; if the provisions in the religious hatred legislation cover some of what is legitimate concern in the existing Common law of Blasphemy then we don't want to go to the stake for the existing position. That I think was why not everybody wanted to put their neck on the line for this particular bit of the law. The concern which the Blasphemy law rightly covers is a concern to protect a general register or tone within our society which is quite simply respectful of disagreement; and there are certain kinds of public utterance or publication which do not respect disagreement or difference. Now, the level at which that impinges on freedom of speech has notoriously been very hard to calculate, but there are areas of concern there, they're not adequately provided for under the existing Blasphemy law. Perhaps they're better catered for in a law about religious hatred, such as has been passed and is now developing in practice. We'll see what happens.

Why not vigorously pursue political power to effect the honouring of the faith-based values one holds, to the greatest degree practical?

Whenever there have been Christian political parties, they've tended to turn into something rather different before very long: groups that are more and more dominated by one social interest or another; groups that let go of radical Christian commitments in order to be acceptable. I'd much prefer to see Christians being 'unreliable' party members -- that is people who always have rather awkward questions about the political affiliations they're in the middle of -- than trying to have a watertight consistent, Christian political approach. The history of all that is pretty unpromising, whether it's Christian Democrats in Europe, or the alliance of certain Christian groupings with the political Right in the USA.

How do you rate the health of the American political system?

Not being an American citizen, I don't think I'd better say very much about that, except to observe a real anxiety about the way in which for high office in the US it's impossible to campaign without what, for British people, are unimaginably vast financial resources. I don't think that's good for a democracy.

Does personal morality impinge on one's attitude to politicians? Are the shadowy areas of a politician's private life relevant to their public credibility?

I don't think there's a watertight distinction here between the public and the private. I deeply deplore the way in which the private life of politicians is a matter for idle prurience and curiosity but I think that if a politician's personal life is characterized by an untrustworthiness in a wide area of relationships, I would have some questions about their trustworthiness in politics. I don't think that's an absolute or simple guide but I'm unwilling to make a complete disjunction here between the private and the public. It's one person we're talking about, and if they are in the habit of untrustworthiness in one area, I'd need to be convinced that they were trustworthy in others.

Is there a fundamental conflict between those who base politics on revelation and those who base politics on reason alone?

I haven't met all that many people who base politics on reason alone. Even if they think they do, they're very often taking for granted a good many hidden moral and even spiritual assumptions. Reason alone is often identified with managing a variety of people's self-interests and that gets you so far, it doesn't get you to the point where politics turns into something a little bit bigger than just the calculation of self-interest, when it understands something about obligation outside the immediate, when politicians act for the sake of the poor elsewhere or for the sake of the environment generations on, or whatever. I don't think that's covered just by classical accounts of self-interest, and in that sense I don't think it's just about reason; there's something about vision and moral energy in there somewhere. So I'm not sure I'd accept an absolute difference between revelation and reason in that connection.

Can politics live without faith?

I think my answer to the last question might suggest that I don't think it can, really, without faith of one sort or another, what I call moral energy and imagination.

Should politicians give direct expression to their religious convictions in framing laws for the benefit of the community?

I hope so. I hope that what makes their minds up as they vote for this or that law is shaped by who they are as people, including their convictions of faith. But that's rather different from saying that their agenda should be dictated by a set of religious principles which they go in to enact (it's the Christian politician/party business again). So I want to see people across the road there, acting on their Christianly-informed consciences when they vote. That's why I believe that there should be a free vote on certain bits of the Human Fertilization and Embryology Bill, incidentally, because that's a conscience issue for so many people.

Should the Archbishop of Canterbury be a (good) politician?

The Archbishop of Canterbury's bound to be a politician in the sense that he has got to think about the understanding and the management of a quite varied and often rather unruly Christian community: the Church of England and the Anglican Church, worldwide. And of course there are politics in that, understanding power, understanding responsibility, transparency, accountability: the Archbishop's bound to be a politician. But in the context of our society, I think an Archbishop – like any other Christian, and particularly any other Christian pastor or teacher – does have the responsibility of trying to move forward the sort of debates I've been talking about, and draw out the assumptions of people in our society about human dignity and human nature: in that sense a politician. And by long tradition the Archbishop is in fact a legislator, and like any other legislator the Archbishop needs to vote according to his conscience. So I hope that when he does that, he is in some sense a 'good' politician.

Is there still a case for an established Church in England? To what extent would the removal of Bishops in the House of Lords result in social anaemia? How do you view the possible loss of the Bishops from a re-organised House of Lords? Isn't having the Queen at its head, itself a political statement by the Church something that inextricably aligns the Church with a certain political view?

The case for the establishment of the Church of England is, I suppose, the case for two things: one, for the recognition by the state of some element in its life, answerable to more than narrowly political interest; the state says 'we keep a place there for a community recognized by us as a state, which looks beyond the boundaries of the immediate political conflicts'. That's one part of the case. The other part is the state's recognition that everyone in the nation has a right to access some kind of spiritual service. Quite a lot of both of those can be met in ways other than the establishment as we now see it. I had ten years as a Bishop in a disestablished Church in Wales without noticing a great deal of difference a lot of the time. So I don't believe in the general principle that disestablishment is lethal for the Church, or that the establishment in its present form is a ditch the Church would have to die in. I have more faith in the Church than that. At the same time if disestablishment meant the pushing of a strong secularizing agenda, or the removing of that sense that a state needs people in it who have obligations and affiliations beyond, to transcendent reality, then I'd be worried. I'd think that the state would lose out in that.

Bishops in the Lords?

In the context of what I've just been saying, that's where the legislature allows that there are people in it licensed to ask awkward questions on a religious basis. They wouldn't in principle have to be bishops and it may well be that in the future of the House of Lords we'll see other religious bodies drawn in; I'm sure that'd be right. But simple removal of Bishops from the Lords might well be the amputation of a genuinely useful part of the polity: not because the Bishops are clinging to privilege, but as a matter of witness to that more than political dimension that I touched upon.

What about the responsibility of Christians to take a stand for human rights, the rights of those suffering injustice, like the plight of Palestine? Why aren't Christians taking an active part in the peace process, claiming their part of the Holy Land?

I think Christians actually are taking a part – sometimes quite prominently – in that discussion. Many of you will be aware of the role that Christians of different confessions have played in the peace process in the Holy Land as elsewhere. And whenever I've been in Jerusalem I've found a remarkable willingness on the part of a number of religious leaders to get together and engage with this, Christian, Jewish and Muslim. My predecessor launched some years ago the Alexandria Process, designed to draw religious leaders of all these traditions into the peace process much more visibly. And in terms of standing up for human rights generally, the rights of the disadvantaged, I think the record of the Church in many contexts worldwide is not bad, and sometimes wonderful. Whether it's the South African history which is, I guess in most people's minds, the history of many of those in Latin America, who've stood alongside the poorest: or the current fact of those in India who so vigorously defend the rights of so-called 'untouchables' in Southern India especially.

Should the current preoccupation with rights be balanced with the greater recognition of responsibilities?

The nature of the Christian Church is that it is a community where people take responsibility to and for each other before God. And the most fundamental question about the moral colouring of the Christian Church is: how effective is that responsibility to and for one another? That is part of what the Church proposes to society as a vision and an ideal.

© Rowan Williams 2008