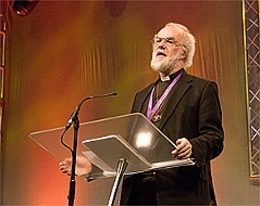

Archbishop's First Presidential Address at Lambeth Conference

Sunday 20th July 2008

With stirring words the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, opened the first full plenary session of the Lambeth Conference at the University of Kent, receiving an enthusiastic reception from bishops from around the world.In his Presidential Address to Lambeth Conference Dr Williams called for reflection and a focus on strengthening the Communion.

"You can all help shape fresh, more honest and more constructive ways of being a Conference – and being a Communion. The Conference seeks to build up a trustful community in this time together – one reason we began with a retreat, so that our common trust in God could be renewed."

"We must be honest about how deep some of the hurts and difficulties currently go; and we must refresh and reanimate our sense of what our Communion ought to be contributing to the whole ecumenical spectrum of Christian life."

"It's my conviction that the option to which we are being led is one whose keywords are of council and covenant. It is the vision of an Anglicanism whose diversity is limited not by centralised control but by consent".

Dr Williams stressed the enormous significance and importance of existing bonds of friendship and fellowship which were, he said, "valuable channels of grace, even if some want to give such bonds a more formal and demanding shape".

"I want to stress this partly because all those existing bonds are already being richly used by God for the service of his world. As we shall be reminded many times during these days, our own communion and unity are created and nourished by God for the sake of the Good News.

"If our efforts at finding greater coherence for our Communion don't result in more transforming love for the needy, in greater awareness and compassion for those whose humanity is abused or denied, then this coherence is a hollow, self-serving thing, a matter of living 'religiously' rather than 'biblically'".

"We seek for clarity about what we must do in a suffering world because....we are at one in knowing what the Incarnate Lord requires of us".

Dr Williams reminded the Conference that "Our endings are in God's hand; the Word, through the Spirit, is transforming us into Christlikeness, so that we may pray trustfully and intimately to our Father. And in that process our relations with each other are transformed, and even our relations with the material world around us. At our roots and at our end is the Word, Jesus our Lord, embodying all that God wants to do first for us and then through us."

Archbishop Williams urged that this transformation should be one not only in word but in deed and in truth.

Transcript of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Presidential Address:

As we begin our work together, we’re bound to be very much aware of people’s eyes upon us. There are expectations among our own people – both hopes and fears. There are expectations among the representatives of the world’s media – and plenty of stories already which seem to know better than any of us what is going to happen. I saw the headline “Is this the end of the Anglican Communion”. No-one has told us here. And there are our eyes on each other – perhaps not quite sure yet how it’s going to feel, who we’re going to be alongside, whether everything will come out right in the sense that after two weeks we shall be able to say something with real integrity that will move us forward in God’s way.

We know all that; but we need also to know what most matters – that God’s eyes are upon us and that God has entrusted something to us. In the last few days, we have had a chance to hold that firmly in mind as we have shared our time of retreat. We have reminded ourselves that God has entrusted something to each one of us as a bishop, the care of his people and the taking forward of his purpose for humankind through our share in God’s mission. We have been caught up in the infinite consequences of Jesus’ life and death and resurrection. We are part of God’s way of making those consequences real and liberating for all humanity. So all that is said and done in our context here is in some way to do with this fundamental agenda, deepening our commitment to God’s own vision of the world’s future in Christ.

But God does not hand out general prescriptions and inspirations: God works through the specifics of the community that is called in Christ’s name – the Church. And the Church is known in diverse forms and traditions. So God has not only entrusted to us the task of sharing in his mission; he has also entrusted to us one particular way embodying and serving this mission. He has entrusted to us this extraordinary thing called the Anglican Communion. And in our time together he is asking us, more sharply than ever before, perhaps, what we want to make of it – how we use the legacy we have been given for his glory and for the sake of the good news of Jesus Christ.

More sharply than ever? Yes, because we all know that we stand in the middle of one of the most severe challenges to have faced the Anglican family in its history. But at the same time, we shouldn’t assume that this is the worst of times. The very first Lambeth Conference met against the background of bitter controversy in Southern Africa and fierce disputes about who was a ‘proper’ bishop and who wasn’t. And if we go back in Church history to the early centuries of the Christian community, we find once again the record of councils meeting in an atmosphere of some suspicion and fear, with people not being at all sure who was supposed to be in charge and who ought and ought not to be present. We haven’t just invented church divisions in the last ten years or so; and there never was a golden age for the Anglican Communion or for the wider Church of God.

When all that has been said, and when we’ve got things into perspective, though, it’s still true that we have some choices ahead of us in these weeks together. And when God gives us choices he also asks us to think and pray about how we make the choices as well as what we actually choose. If what we want more than anything is to be guided by the Holy Spirit, and I’m taking it for granted that is what we want, who alone can make Christ alive in our midst, we shall want to find a way of letting that guidance be as powerful and as real as it could be. So I’d like at this point to say a few more words about the new methods we’re using in this Conference, the methods you’ve been hearing about this afternoon.

Quite a few people have said that the new ways we’re suggesting of doing our business are an attempt to avoid tough decisions and have the effect of replacing substance with process. To such people, I’d simply say, ‘How effective have the old methods really been?’ Earlier Lambeth Conferences issued weighty reports and passed scores of resolutions (I must put my hand up and admit that I’ve drafted parts of those reports and resolutions myself in the past!); no-one would say they have been a waste of time, because they still embody a lot of careful thinking and planning. Yet not much of this material attempts to convey what was different about meeting in a prolonged time of prayer and fellowship as we always do at these Conferences. And as for resolutions: if you look at the resolutions that have been passed since 1867, you’ll find many of them, on really important subjects, have never been acted on. At the very first Lambeth Conference, the assembled bishops passed a resolution asking for some kind of supreme canonical court in the Communion which could settle points of dispute in provinces. What happened to that resolution, I wonder. Often we have passed a motion but not thought what would be necessary to make it take effect.

So before we assume too quickly that a Conference with large preparatory books and many resolutions is the proper or the most fruitful way of going about things, we might need to pause and recognise that in this respect too there has never been a golden age of Lambeth Conferences! What has been uppermost in the minds of the group – the devoted and brilliant group, to my mind – that has put together this Conference has been a couple of basic considerations which I hope everyone will keep in mind in the days ahead.

First, as you have heard, they recognised, with the help of those members who came from outside Europe and North America, that the methods we had got used to were very much tied to Western ways – and not only Western ways, but the habits that developed in the later twentieth century, with tight procedural rules, great quantities of paper, close timetables and yes-or-no decisions. All these still have their attractions, but, as I’ve said, it isn’t clear that they actually help things happen any more effectively when you’re dealing with a large and very varied group. What’s more, this sort of method guaranteed that the voices most often heard would be the voices of people who were comfortable with this way of doing things; but what would it take to guarantee that everyone’s voice has a chance of being heard?

Second, connected with this, decisions are most effective when they are really ‘owned’ by the greatest possible number of people involved; when they reflect a discussion in which everyone is confident that they haven’t been manipulated, bullied or ignored. Even if the decision doesn’t come out exactly where they wanted, they can still be confident that they haven’t been sidelined or silenced. So what would it take to have an outcome from an event like this that the overwhelming majority felt they had shaped for themselves?

The process of the Conference as it’s now unfolding is an attempt to answer those questions – and not only to answer them, but to lay foundations for working better in the future. In institutional terms, we need renewal, and this is the moment for it. If you will, you can all help shape fresh, more honest and more constructive ways of being a Conference – and being a Communion. The Conference seeks to build up a trustful community in this time together – one reason we began with a retreat, so that our common trust in God could be renewed. We shall get to know a relatively small number of people really well in the Bible Study groups. This has always been one of the great features of the Lambeth Conferences, and my best memories of these gatherings have been in this context. But this time we want to build on them further, so that, as a group of Bible Study groups meets to make up the Indaba group, something of the same process will be reproduced as people open up more fully to each other.

Everything depends of course on everyone being ready to play their part. It means giving attendance at these groups an absolute priority during our time together. It means being willing to contribute, to share what’s on your mind and heart. It means being ready to listen to what someone else is saying and not leap to hostile or suspicious conclusions. Please, please, give of your best to this; expect the Spirit of God to be at work in this; remembering the Dean of Canterbury’s words about the mission statement of the Cathedral, keep praying the words of the Greeks in John 12, ‘We want to see Jesus.’

But the big challenge then is to draw the life of all these groups together. The indaba process is meant to clarify what the real questions and concerns are, so that everyone comes to have some sort of shared perspective on things, even if they don’t yet agree. There remains the task of finding an overview of this, and this is why we have nominated certain people to listen and report and work with each other to bring that overview into being. We also have to draw upon the hard work of the two groups we have met this afternoon, those who have worked on the draft of a possible Covenant for our life together and those who have made up the ‘Windsor Continuation Group’. They have had one of the toughest jobs of anyone connected with this Conference because they have had to think through what needs to happen for the insights and proposals of the Windsor Report to go on steering our common life in the Communion in ways that will prevent further strain and division.

The work of the indaba groups and that of these more formal working parties will affect and inform each other in our meetings; and this lays a special responsibility on those who are doing the listening and reflecting for us and who are managing the various ‘hearings’ that will take place so that all who wish can comment on how some of these matters are advancing and developing. Archbishop Roger Herft has explained something of this process. And our hope is that we shall end up with a ‘Reflection’ from the Conference that is not a set of resolutions and decisions, but which does genuinely change the situation and take us forward. It’s a difficult balance to achieve. All of us are involved in making it work.

But what of these problems, what of the future of the Communion? In what I have said there may be a hint of how we should think about this. Because the greatest need of the Communion now is for transformed relationships. This does not mean simply warm feelings about each other, but new habits of respect, patience and understanding that are fleshed out in specific ways and changed habits – in responsible agreement and search for the common mind, in constant active involvement in the life of other parts of the family, and, as I suggested in the retreat, in shared commitments to a rule of life and a pattern of prayer, so that it remains possible to see in the other person another believer, another redeemed sinner, another person on the way to transformation in Christ. We need to get beyond the reciprocal impatience that shows itself in the ways in which both liberals and traditionalists are ready – almost eager at times, it appears – to assume that the other is not actually listening to Jesus.

For this to be a reality, we must be honest about how deep some of the hurts and difficulties currently go; and we must refresh and reanimate our sense of what our Communion ought to be contributing to the whole ecumenical spectrum of Christian life. We cannot ignore the fact that what is seen to be a new doctrine and policy about same-sex relations, one that is not the same as that of the vast majority at the last Lambeth Conference, is causing pain and perplexity. We cannot ignore the pressures created by new structures that are being improvised in reaction to this pain and perplexity, pressures that are very visible in the form of irregular patterns of ministry across historic boundaries. Perspectives on the situation are very different at the moment. Some in our Communion would be content to see us become a loose federation, perhaps with diverse expression of Anglicanism existing side by side in more or less open competition but with little co-ordination of mission, little sense of obligation to sustain a common set of theological and practical commitments. Some would like to see the Communion as simply a family of regional or national churches strictly demarcated from each other – sovereign states, as it were, with independent systems of government, coming together from time to time for matters of common concern. Others again want to see a firmer and more consistent control of diversity, a more effective set of bodies to govern the local communities making up the Communion.

Each of these is attractive in some ways to people at both ends of the theological spectrum. Yet each of them represents something rather less than many – perhaps most – Anglicans over the last century at least have hoped for in their Communion. A federation of such variety that different parts of it could be in direct local competition is not really a federation at all, and would encourage some of the least appealing kinds of religious division. An ensemble of purely national or local churches both ignores the complexities of a globalised society and economy and seems to make little of the historic and biblical sense of churches in diverse places learning from each other, challenging one another and showing responsibility to each other. A centralised and homogenised Communion could be at the mercy of powerfully motivated groups from left or right who wanted to redefine the basic terms of belonging, so that Anglicanism becomes a confessional church in a way it never has been before.

Is there another option? Along with many in our Communion since the Lambeth Conferences began and international Anglicanism started to have a new kind of visibility, I believe there is; but it will require some of what we take for granted to change. Because it is not an option to hope that we can somehow just carry on as we always have: the rival bids to give Anglicanism a new shape are too strong, and we need to have a vision that is at least as compelling and as theologically deep as any other in the discussion. Without this, trying to carry on as ‘normal’ will unquestionably drift towards one or other of the options I’ve outlined, without proper thought or planning or a sense of the cost of each of them to what we value most in our heritage. That is why there is quite properly a sense of being at a deeply significant turning point.

It’s my conviction that the option to which we are being led is one whose keywords are of council and covenant. It is the vision of an Anglicanism whose diversity is limited not by centralised control but by consent – consent based on a serious common assessment of the implications of local change. How do we genuinely think together about diverse local challenges? If we can find ways of answering this, we shall have discovered an Anglicanism in which prayerful consultation is routine and accepted and understood as part of what is entailed in belonging to a fellowship that is more than local. The entire Church is present in every local church assembled around the Lord’s table. Yet the local church alone is never the entire Church. We are called to see this not as a circle to be squared but as an invitation to be more and more lovingly engaged with each other.

Someone once said about our Communion, in relation to its internal strains and differences, ‘What an astonishing number of possibilities God has given you for loving strangers and enemies!’ Can we echo that? If so, by God’s grace, we have it in us to be a Church that can manage to respond generously and flexibly to diverse cultural situations while holding fast to the knowledge that we also free from what can be the suffocating pressure of local demands and priorities because we are attentive and obedient to the liberating gift of God in Jesus and in the Scripture and tradition which bear witness to him. Already our Bible Study Groups are bringing this into focus. And I want to say very clearly that the case for an Anglican Covenant is essentially about what we need in order to give this vision some clearer definition.

The one thing this is not is a short cut of any sort. It implies, of course, some obvious and simple things – being clear (to take an obvious example) about how we recognise and accept each other’s ministries in the conviction that we are ordaining men and women to one ministry in one Body. But it means also a deeper seriousness about how we consult each other – consult in a way that allows others to feel they have been heard and taken seriously, and so in a way that can live with restraint and patience. And that is a hard lesson to learn, and one that still leaves open what is to happen if such consultation doesn’t result in agreement about processes. There will undoubtedly, in our time together, be some tough questions about how far we really want to go in promising mutual listening and restraint for the sake of each other.

That’s why a Covenant should not be thought of as a means for excluding the difficult or rebellious but as an intensification – for those who so choose – of relations that already exist. And those who in conscience could not make those intensified commitments are not thereby shut off from all fellowship; it is just that they have chosen not to seek that kind of unity, for reasons that may be utterly serious and prayerful. Whatever the popular perception, the options before us are not irreparable schism or forced assimilation. We need to think through what all this involves in the conviction that all our existing bonds of friendship and fellowship are valuable and channels of grace, even if some want to give such bonds a more formal and demanding shape.

I want to stress this partly because all those existing bonds are already being richly used by God for the service of his world. As we shall be reminded many times during these days, our own communion and unity are created and nourished by God for the sake of the Good News. If our efforts at finding greater coherence for our Communion don’t result in more transforming love for the needy, in greater awareness and compassion for those whose humanity is abused or denied, then this coherence is a hollow, self-serving thing, a matte of living ‘religiously’ rather than ‘biblically’, to refer back to the theologian I quoted during the retreat, William Stringfellow. Contrary to what some have claimed, it is not true that we at this Conference are using issues like the Millennium Development Goals to provide a rallying-point for Anglicans who can agree only about ‘secular’ priorities but not about the essence of the Gospel.

No: we seek for clarity about what we must do in a suffering world because we are surely at one in knowing what the Incarnate Lord requires of us – and so at one in acknowledging his supreme and divine authority. And we know that clarity about our calling in this world is no substitute for this unity in faith and obedience. But we also know that how we think about that unity is itself affected by the urgency of the calls on our compassion and imagination; some sorts of division undoubtedly will seem a luxury in the face of certain challenges – as many Christians in Germany found when confronted by Hitler. We have to think and pray hard about what the essentials really are. So we can’t easily pull these issues apart; and we certainly can’t use one as an excuse for not addressing the other.

Meanwhile, one thing you will have noticed is the ample opportunity for learning that is provided by the self-select groups and the fringe events. Use these as fully as you are able. Remember that learning is just that – not necessarily agreeing, but making sure that you have done all that is humanly possible in order to understand. If you have not had the chance to hear directly of the experience of gay and lesbian people in the Communion, the opportunity is there. If you do not grasp why many traditionalist believers in various provinces feel harassed and marginalised, go and listen. If you need some time and space to think through the Covenant proposals outside the opportunities in the main timetable, including hearing strong arguments for and against, the doors are open. No-one’s interests are best served by avoiding the hard encounters and the fresh insights. Bear in mind that in this Conference we are committed to common prayer and mutual care so that the hard encounters can be endured and made fruitful.

To conclude: I wonder if you noticed how the readings at our service this morning – they were from the Church of England lectionary; that’s what we had; there was no forethought – helped to ‘frame’ all our business in the context of the eternal and historical work of Christ? The gospel spoke of the seed sown by the Saviour – the Word of God, who was in the beginning, in whom all things hold together. Our beginnings are in his hand; it is from the gift of the Word made flesh that all our life as Church flows. And the epistle (Romans 8) spoke of endings – the creation set free as God’s children discover their true freedom and glory is revealed in the world we know. Our endings are in God’s hand; the Word, through the Spirit, is transforming us into Christlikeness, so that we may pray trustfully and intimately to our Father. And in that process our relations with each other are transformed, and even our relations with the material world around us. At our roots and at our end is the Word, Jesus our Lord, embodying all that God wants to do first for us and then through us. At every point, he works in us so that our relations with God and each other may be transformed; the life and process of this Conference will be a crucial part of that transformation. As I said earlier, it won’t solve all our problems straight away; but we shan’t find a genuinely Christlike way forward without such transformation. May this happen not only in word but in deed and in truth.

© Rowan Williams 2008