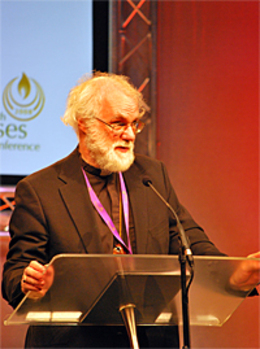

Archbishop's Second Presidential Address at Lambeth Conference

The Archbishop speaking at the Lambeth Conference

The Archbishop speaking at the Lambeth ConferenceTuesday 29th July 2008

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, at the Lambeth Conference 2008.'What is Lambeth '08 going to say?' is the question looming larger all the time as this final week unfolds. But before trying out any thoughts on that, I want to touch on the prior question, a question that could be expressed as 'Where is Lambeth '08 going to speak from?'. I believe if we can answer that adequately, we shall have laid some firm foundations for whatever content there will be.

And the answer, I hope, is that we speak from the centre. I don't mean speaking from the middle point between two extremes — that just creates another sort of political alignment. I mean that we should try to speak from the heart of our identity as Anglicans; and ultimately from that deepest centre which is our awareness of living in and as the Body of Christ.

We are here at all, surely, because we believe there is an Anglican identity and that it's worth investing our time and energy in it. I hope that some of the experience of this Conference will have reinforced that sense. And I hope too that we all acknowledge that the only responsible and Christian way of going on engaging with those who aren't here is by speaking from that centre in Jesus Christ where we all see our lives held and focused.

And, as I suggested in my opening address, speaking from the centre requires habits and practices and disciplines that make some demands upon everyone — not because something alien is being imposed, but because we know we shall only keep ourselves focused on the centre by attention and respect for each other — checking the natural instinct on all sides to cling to one dimension of the truth revealed. I spoke about council and covenant as the shape of the way forward as I see it. And by this I meant, first, that we needed a bit more of a structure in our international affairs to be able to give clear guidance on what would and would not be a grave and lasting divisive course of action by a local church. While at the moment the focus of this sort of question is sexual ethics, it could just as well be pressure for a new baptismal formula or the abandonment of formal reference to the Nicene Creed in a local church's formulations; it could be a degree of variance in sacramental practice — about the elements of the Eucharist or lay presidency; it could be the regular incorporation into liturgy of non-Scriptural or even non-Christian material.

Some of these questions have a pretty clear answer, but others are open for a little more discussion; and it seems obvious that a body which commands real confidence and whose authority is recognised could help us greatly. But the key points are confidence and authority. If we do develop such a capacity in our structures, we need as a Communion to agree what sort of weight its decisions will have; hence, again, the desirability of a covenantal agreement.

Some have expressed unhappiness about the 'legalism' implied in a covenant. But we should be clear that good law is about guaranteeing consistence and fairness in a community; and also that in a community like the Anglican family, it can only work when there is free acceptance. Properly understood, a covenant is an expression of mutual generosity — indeed, 'generous love', to borrow the title of the excellent document on Inter-Faith issues which was discussed yesterday. And we might recall that powerful formulation from Rabbi Jonathan Sacks — 'Covenant is the redemption of solitude'.

Mutual generosity : part of what this means is finding out what the other person or group really means and really needs. The process of this last ten days has been designed to help us to find out something of this — so that when we do address divisive issues, we have created enough of a community for an intelligent generosity to be born. It is by no means a full agreement, but it will, I hope, have strengthened the sense that we have at least a common language, born out of the conviction that Jesus Christ remains the one unique centre.

And within that conviction, what has been heard? I want now to engage in what might be a rather presumptuous exercise — and certainly feels like a risky one. I want to imagine what people on different sides of our most painful current debate hope others have heard or are beginning to hear in our time together. I want to imagine what the main messages would be, within an atmosphere of patience and charity, from those in our Communion who hold to a clear and traditional doctrinal and moral conviction, and also from those who, starting from the same centre, find fewer problems or none with some recent innovations. Although these voices are inevitably rooted in the experience of the developing world and of North America, the division runs through many other provinces internally as well.

So first : what might the traditional believer hope others have heard? 'What we seek to do in our context is faithfully to pass on what you passed on to us — Holy Scripture, apostolic ministry, sacramental discipline. But what are we to think when all these things seem to be questioned and even overturned? We want to be pastorally caring to all, to be "inclusive" as you like to say. We want to welcome everyone. Yet the gospel and the faith you passed on to us tell us that some kinds of behaviour and relationship are not blessed by God. Our love and our welcome are unreal if we don't truthfully let others know what has shaped and directed our lives — so along with welcome, we must still challenge people to change their ways. We don't see why welcoming the gay or lesbian person with love must mean blessing what they do in the Church's name or accepting them for ordination whatever their lifestyle. We seek to love them — and, all right, we don't always make a good job of it : but we can't just say that there is nothing to challenge. Isn't it like the dilemma of the early Church — welcoming soldiers, yet seeking to get them to lay down their arms?

'But please remember also that — while you may say that what you do needn't affect us — your decisions make a vast difference to us. In this world of instant communication, our neighbours know what you do, and they see us as sharing the responsibility. Imagine what that means where those neighbours are passionately traditional Christians — and what it means for our own members, who will be drawn to leave us for a "safer", more orthodox church. Imagine what it means when those neighbours are non-Christians, delighted to find a stick to beat us with. Imagine what it is to be known as the 'gay church' in a context where that spells real contempt and danger.

'Don't misunderstand us. We're not looking for safety and comfort. Some of us know quite a lot about carrying the cross. But when that cross is laid on us by fellow-Christians, it's quite a lot harder to bear. Don't be too surprised if some of us want to be at a distance from you — or if we want to support minorities in your midst who seem to us to be suffering.

'But we are here. We've taken a risk in coming, because many who think like us feel we've betrayed them just by meeting you. But we value our Communion, we want to understand you and we want you to understand us. Can you find some way of being generous that helps us believe you care about us and about the common language and belief of the Church? Can you — in plain words — step back and let us think and pray about these things without giving us the impression that the debate is over and we've lost and that doesn't matter to you?'

And then : what might the not so traditional believer hope has been heard?

'What we seek to do in our context is to bring Jesus alive in the minds and hearts of the people of our culture. Trying to speak the language of the culture and relate honestly to where people really are doesn't have to be a betrayal of Scripture and tradition. We know we're pushing the boundaries — but don't some Christians always have to do that? Doesn't the Bible itself suggest that?

'We are often hurt, angry and bewildered at the way many others in the Communion see us and treat us these days — as if we were spiritual lepers or traitors to every aspect of Christian belief. We know that no-one is the best judge in their own case, but we see in our church life at least some marks of the Spirit's gifts. And part of that is acknowledging the gifts we've seen in gay and lesbian believers. They will certainly be likely to feel that the restraint you ask for is a betrayal. Please try to see why this is such a dilemma for many of us. You may not see it, but they're still at risk in our society, still vulnerable to murderous violence. And we have to say to some of you that we long for you to speak up for your gay and lesbian neighbours in situations where they are subject to appalling discrimination. There have been Lambeth Resolutions about that too, remember.

'A lot of the time, we feel we're being made scapegoats. Other provinces have acute moral and disciplinary problems, or else they more or less successfully refuse to admit the realities in their midst. But those of us who have faced the complex issues around gay relationships in what we feel to be an open and prayerful way are stigmatised and demonised.

'Not all of us, of course, supported or took part in the actions that have caused so much trouble. Some of us remain strongly opposed, many of us want to find ways of strengthening our bonds with you. But even those who don't stand with the majority on innovations will often feel that the life of a whole church, a life that is varied and complex but often deeply and creatively faithful to Christ and the Scriptures, is being wrongly and unjustly seen by you and some of your friends.

'We want to be generous, and we are hurt that some throw back in our faces both the experience and the resources we long to share. Can you try and see us as fellow-believers struggling to proclaim the same Christ, and to be patient with us?'

Two sets of feelings and perceptions, two appeals for generosity. For the first speaker, the cost of generosity may be accusation of compromise : you've been bought, you've been deceived by airy talk into tolerating unscriptural and unfaithful policies. For the second speaker, the cost of generosity may be accusations of sacrificing the needs of an oppressed group for the sake of a false or delusional unity, giving up a precious Anglican principle for the sake of a dangerous centralisation. But there is the challenge. If both were able to hear and to respond generously, perhaps we could have something more like a conversation of equals — even something more like a Church.

At Dar-es-Salaam, the primates tried to find a way of inviting different groups to take a step forward simultaneously towards each other. It didn't happen, and each group was content to blame the other. But the last 18 months don't suggest that this was a good outcome. Can this Conference now put the same kind of challenge? To the innovator, can we say, 'Don't isolate yourself; don't create facts on the ground that make the invitation to debate ring a bit hollow'? Can we say to the traditionalist, 'Don't invest everything in a church of pure and likeminded souls; try to understand the pastoral and human and theological issues that are urgent for those you are opposing, even if you think them deeply wrong'?

I think we perhaps can, if and only if we are captured by the vision of the true Centre, the heart of God out of which flows the impulse of an eternal generosity which creates and heals and promises. It is this generosity which sustains our mission and service in Our Lord's name. And it is this we are called to show to each other.

At the moment, we seem often to be threatening death to each other, not offering life. What some see as confused or reckless innovation in some provinces is felt as a body-blow to the integrity of mission and a matter of literal physical risk to Christians. The reaction to this is in turn felt as an annihilating judgement on a whole local church, undermining its legitimacy and pouring scorn on its witness. We need to speak life to each other; and that means change. I've made no secret of what I think that change should be — a Covenant that recognizes the need to grow towards each other (and also recognizes that not all may choose that way). I find it hard at present to see another way forward that would avoid further disintegration. But whatever your views on this, at least ask the question : 'Having heard the other person, the other group, as fully and fairly as I can, what generous initiative can I take to break through into a new and transformed relation of communion in Christ?'