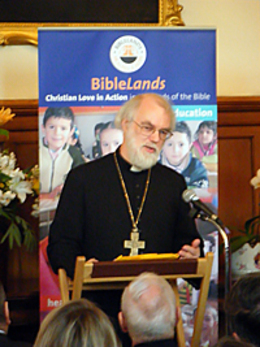

Archbishop at BibleLands conference - 'more dramatic and more costly' change for Christians in the Middle East

Wednesday 16th April 2008

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, hosted and addressed a conference at Lambeth Palace for the charity BibleLands examining the challenges facing Christian communities in the Middle East.(Full text of the Archbishop's address is below.)

The conference, entitled 'The Christian Presence',sought to examine and reflect the conditions in which Christian communities in the Middle East are living and how Christians in the UK can create a positive difference to the current situations found in countries like Iraq, Israel and Egypt.

BibleLands is a non-governmental, non-denominational, Christian charity working in partnership with Christian-led Projects in the lands of the Bible. Established in 1854, the work of BibleLands focuses on education, special needs, social & medical care, vocational & adult training and the support & care of refugees. The ethos of the charity is to share the compassion of Jesus as they tend, treat and teach the young, the sick and the needy and seek to bring the peaceful things of God to those in most need – regardless of their faith or nationality.

Dr Williams addressed the conference alongside Archbishop Paul Sayah (Maronite Archbishop of Haifa and the Holy Land) and Bishop Angaelos (General Bishop of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the UK). Following the three lectures there was a pause for evening prayer and then a question and answer session to a panel of guests, chaired by Lord Steel. The panel was comprised of:

Dr Williams addressed the conference alongside Archbishop Paul Sayah (Maronite Archbishop of Haifa and the Holy Land) and Bishop Angaelos (General Bishop of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the UK). Following the three lectures there was a pause for evening prayer and then a question and answer session to a panel of guests, chaired by Lord Steel. The panel was comprised of:

| Dr Rowan Williams | Archbishop of Canterbury |

| Dr Paul Sayah | Maronite Archbishop of Haifa and the Holy Land |

| H G Bishop Angaelos | Bishop of Coptic Orthodox Church in the UK |

| Rev Dr Shafiq Abouzayd | Aram Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies |

| Rev Daniel Burton | Chairman, BibleLands |

| Dr Harry Hagopian | Middle East Ecumenical & Political Consultant |

| Rev Gendi Ibrahim Rizk | El Saray Evangelical Church, Alexandria |

Describing the situation of Christians in the Middle East, the Archbishop said:

"There is an urgent need for people in the UK to wake up to the fact that Christians in the Middle East are living through a time of change more dramatic and more costly than anything that has been seen for a thousand years and more. Apart from the tragic situation of Christian refugees from Iraq, there is a quiet but numerically huge exodus of Christians - especially but not exclusively educated Christians - from the whole region. The remaining Christian communities are left exposed to violence or extremism in many countries, and the societies they live in are deprived of some of their most creative and resourceful citizens.

We badly need to be better informed about both the present and the past of these communities. The publication by the Middle East Council of Churches of a comprehensive book on Christianity: A History in the Middle East gives us a first rate tool for learning about the historical background.

But we are also announcing today the funding of a scholarship to study the impact of migration among Iraqi Christians, supported by the Archbishop's Mission to the Assyrians, the Philip Usher Fund and the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association. In addition to this, the Nikaean Ecumenical Trust is giving a Bishop Buxton Bursary to two Syrian Orthodox deacons from Lebanon to study English in the UK for two months and to learn something of our own Church.

These are small gestures in the overall context of anxiety and suffering for our brothers and sisters in the Middle East, but our hope is that they will do something to raise awareness on behalf of Christian communities in the ancient heartlands of faith who so often feel ignored or forgotten by us their Western fellow-Christians."

A full transcript of the Archbishop's speech follows:

Thank you very much for those kind words. Your Eminences, Your Graces, friends, it is a very great delight to be able to welcome you here this evening for this event which I hope will be not only a celebration but also an injection of energy for the next hundred and fifty years or more.

I want to begin with a story which I think will be familiar in one or another form to many of you. One of my Palestinian friends speaking about an encounter with a western Christian who asked him, "When did your family become Christian?", to which he replied, "About two thousand years ago!" What I want to do in my opening remarks this evening is to just set the scene a little bit with the historical background of Christians in the Middle East to raise the question of why their position has changed and become so much more vulnerable within our own lifetimes and to open up some issues of where we might go in supporting, enriching and being enriched by the life of Christian communities in the Middle East. The historical background is not insignificant because anyone who has ever had anything to do with those who haven't got a strong or long-term interest in the Church will be aware of how much ignorance there is in our country and culture generally about Christians in the Middle East, even, dare I say, at the level of Government. It is remarkable how many people you come across who think that Christians arrived in the Middle East about a hundred years ago because, of course, before that, from time immemorial, they had all been Muslims. There is something slightly odd about this picture of Middle Eastern history to put it mildly and it encourages some very unrealistic and unconstructive policies on all sides.

I needn't labour the point that the Christian communities of the Middle East have indeed been there since the beginnings of Christianity, but perhaps it is worth saying a little bit about the role they have played in the intervening centuries. The first great shock to those historic communities was, of course, the rise of Islam. One shouldn't in that framework forget how much the politics of the region, even at that point, played a role in the development of society and governance in the Middle East. There were many of those in the Middle East at that time who preferred to welcome Muslim invaders to living under the rule of the Empire of Byzantium, operating what they would regard as a rather doubtful theology applied with a very heavy hand. So even the ministry of Byzantine Christianity in the Middle East is not innocent. Very little history is!

But in the centuries which followed, one of the things that is most striking to the objective reader of history is what an extraordinary and pivotal, entrepreneurial role Christians communities played in the centuries of Muslim rule in the Middle East. It is well known that it was the Syrian Christian communities who transmitted to the Muslim world the heritage of Greek medicine, mathematics and philosophy. It is less well known that right up until the Middle Ages, in Syria, in Iraq, and in Egypt, Christian physicians, philosophers, and teachers continued to play a crucial role in the management of a number of Muslim states. It has been said, and I am not an Arabist so I can't judge the accuracy of this, but it has been said by those who ought to know that the maintenance of variegated, sophisticated literary culture and intellectual culture in the Arabic language was from the 8th century to the 11th/12th century very much the responsibility of those Christians who continued to support and inform the life of the Muslim states in which they lived and worked. So that, alongside the undoubted history of civil and legal disadvantage under which Christians lived in so many of these states, there was also that crucial role of being, perhaps one could say, a broker of cultural goods within the Muslim world – Christians who kept alive certain sorts of intellectual understanding, certain sorts of imaginative possibility.

The arrival of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East and its great triumphs in the 15th and 16th centuries made a considerable difference. It created for the first time a huge single authority stretching from the Balkans to central Asia and to the borders of Ethiopia. And within that context it was far less easy for Christian communities to have the role that they had previously. And yet, once again, one can see, especially as the centuries move on, how the Christian presence within the Ottoman Empire began to play, more and more, the same sort of role. It began to stimulate and to challenge and to enlarge.

The renaissance of Arab culture in the 19th century owed an enormous amount to Christian communities. During that century, some may be surprised to learn, the demographic pattern in the Ottoman Empire has pointed to an increased percentage of the Christian populations. That in its turn brought instabilities. In the later part of the 19th century we see the succession of appalling atrocities committed against Christian communities, again from the Balkans to the borders of central Asia. The genocidal violence that was practised against so many of the Christian minorities; Syrian Christians, Armenian Christians, Assyrian Christians and of course Orthodox Christians in the Balkans as well – and the burden fell very heavily on those communities which Your Grace {indicating Metropolitan Athanasius, Bishop of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the UK & Ireland} represents in effect this evening. It was partly a reaction against the perception that Christians were indeed playing the role of a leaven in the lump, raising questions about the governments of the Ottoman Empire, about justice and efficiency in the system, about the best way in which those communities which composed the Ottoman Empire might live with Western powers.

One of the great paradoxes of the history of this period is that so much of what emerged in the early 20th century as Arab nationalism and Turkish nationalism has many of its roots in the Christian thinkers and writers of the later 19th century in the Middle East. Within the 20th century Christian intellectuals, particularly in Syria, had a key part in shaping the ideals of a secular society respectful of all religions. That was a major role once again played by Christians in this region.

Now I underline all this, partly because it is a history that most of us are not very familiar with and partly because I think that it is important to challenge the idea that the historic Christian communities of the Middle East are just museum pieces. We may say that it is very nice that they have been there for such a long time and they have all kinds of interesting rituals and practices and that they are very picturesque. I want to suggest that the history is a great deal more than that, at its very best the history of Christians in the Middle East, Syrians, Armenians, Copts and others, has been a history of intellectual stimulus, of creativity, of constructive social challenge, even within the most difficult of circumstances. I think we ought to acknowledge that with gratitude as Western Christians.

It is sometimes said that the history of the Near East is a history that was until fairly recently of happy religious co-existence; well that's overstating it considerably. There has never been a golden age in Middle Eastern history and as I've indicated, massacres and, genocidal violence against Christians has sadly occurred again and again in the history of the region. And yet it is fair to say that up until the later part of the 20th century, you could have said of many parts of the Middle East that there was at least an assumption that different faiths should be capable of living together and entering into constructive, political and social dialogue as well as dialogue at the level of faith and theology.

What has made the difference? Because it will be very hard today to point to the Middle East as a region where it was taken for granted that the different religious traditions could live together in harmony. There's no one quick answer to the question of what has happened. But, one could point to two major factors which in a strange way are interrelated. The development of Arab nationalism, owing so very much to Christian inspiration originally, reached a kind of peak perhaps in the 1940's and 1950's and then somehow ran out of political energy leaving a vacuum into which it was very easy for the more extreme forms of Islam, bit by bit, to spread. The assumption that Arab and Muslim were interchangeable terms began to get a tighter grip in the region and that remains, internally and externally, one of the great problems that we face. It is a point that I have gone back to again and again in recent years and it is crucial to the health of the region and of the world that we don't assume that Arab and Muslim are equivalent terms; that at its best the Arab world has been a pluralist world. I shall come back to that question a little bit later. So the rise and then fall of a certain kind of secular Arab nationalism left a vacuum into which unfriendly forms of Islamic extremism could and eventually did penetrate.

The creation of the state of Israel for all kinds of intelligent, historical reasons produced in that area another highly self conscious national body creating any number of conflicts and tensions, which I won't elaborate on now. It played into the fears and anxieties of Muslim communities in the region and its relationship to the indigenous Christian communities in the region has always been complex.

These are simply historical facts about what has changed the shape of the Middle East, but until fairly recent years we could discuss this question without naming a third and at present perhaps the most globally troubling factor which has produced change. The military policies of the West in the last few years have firmly cemented in a great deal of the Middle East the notion that Christianity is a foreign, aggressive and Western presence. Indigenous Christian communities throughout the region have suffered from being associated with the American global project and indeed at times the British global project, as part of the American global project as sometimes it has been. And I am sure that those closer to the painful realities on the ground at the moment will confirm the appalling pressure that has created for one after another of the historic Christian communities in the Middle East. It is to be seen in Palestine, it is to be seen in Iraq, it is to be seen elsewhere as well. It means that communities that have a history of co-existence suddenly have become antagonistic. It means that pressure on Christian groups locally has increased so intensely that the rate of migration has increased by an almost incalculable factor. To speak in that context of local Muslim pressure of Christian communities is not to make a glib point about Christianity and Islam; simply to recognise the effects of the policies of the last decade on the real life of local communities. A factor which I would hope Western governments become more conscious of than they are at present. This is part of the effect of decisions made here, part of the responsibility that Western governments carry.

At present the pressures on so many of our Christian brothers and sisters in the Middle East are well nigh intolerable. Migration which in the 19th and early 20th centuries was a positive thing for Christian communities in the Middle East, a way of extending their experience and their engagement with global culture, has now become a desperate measure to get away from an unbearable situation and one of the biggest anxieties which I would guess is shared by most people in this room is the prospect of the Middle East without a vital, creative Christian presence – such as its history might suggest – and the reduction particularly of the Christian sites of the Holy Land to being museums. If the Holy Land itself, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, are not to be theme parks as far as Christianity is concerned then Christians elsewhere in the world need to keep their responsibility and their awareness keen – that's part of why we're here this evening I would suggest.

Just to illustrate this point, I think one of the most harrowing and difficult afternoons I have had in recent months was the time spent in Syria with a couple of hundred Christian refugees from Iraq. Last autumn I was privileged to see some of the work done by the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate with those refugees in Syria. Their work is exemplary, heroic. Indeed the response of Syria to the influx of Iraqi refugees has been until recently very generous. But the load that is thereby put on Syria itself is unbearably heavy and the state of those refugees is a matter of deep concern and indeed, I would say, scandal. We know and we have been reminded in recent weeks in the most vivid way possible, of the threats and the pressures under which Iraqi Christians live. We know therefore how far away we are from a peaceful settlement, from security within Iraq for all its communities. We know so long as that continues, the pressure is on for not only Iraqi Christians to leave but for other neighbouring countries to have to bear the burden in ways that they are not well equipped to do. I regard it as a real tragedy that this ongoing crisis is yet to be the subject any firm policy declaration or indeed even recognition by some of our Western governments. We can say a great deal about those pressures and others here this evening. Others will say more from firsthand experience but I simply want to put that against the background of which I began.

The history of Christian communities in the Middle East is a history that suggests a real capacity for the presence of Christians at the heart of the Arab world to be a presence that is a creative possibility. I would say that is what we must pray for and work for once again. If that is not the case, we do run the risk of a monochrome Islamic Middle East; not only Islamic but dominated but forms of Islam that are most unfriendly to the rest of the world. We need to see the democratic, argumentative, interactive, creative society in that region which will only come if all religious communities there – Christians, Muslims and Jews – are able to engage in that way.

What can we do? I hope that in this evening's discussion we shall have some suggestions about this, but I would mention just one or two things which we are trying to do from here in response to the critical situation in the Middle East. We have been able to arrange for a Deacon in the Syrian Orthodox Church to spend time here in the United Kingdom in St Stephen's House to share experience of that Church and that people with us. We are also setting up a scholarship whose purpose will be the study of the impact of migration on the Iraqi Christian communities. The Scholarship will be funded mainly by the Philip Usher Fund but also from the Archbishop of Canterbury's Mission to the Assyrians (an historic 19th century foundation) and the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association; because we need to have the best possible research and information on the status of Christians in the region if we are to make informed judgements. These are very small things indeed. There is much more that many of us ought to be able to do, not least in continuing to put the facts before our democratically elected representatives in this country. But in terms of spreading information, perhaps I may be excused a quite shameless plug for a book published by the World Council of Churches, 'Christianity, a history in the Middle East'. A wonderfully comprehensive account of the last two thousand years of Christianity in the region which brings vividly to light all these images of the history of the region which seem to me to be so important in our understanding of it.

I won't detain you longer but in conclusion let me once again underline what I think is the positive goal to which we ought to have in mind at least. For centuries Christian communities have been a vital part of the political and social and cultural health of the Middle East. A region deprived of that contribution becomes a region more unstable, more open to the pressures of fanaticism, less able to deal with its own internal problems and less able to deal with the rest of the world. We should give as much effort as we are capable of in ensuring that monochrome, inward looking and inherently unstable future does not happen. And that means addressing these issues wherever they arise; and addressing some of the root causes as well. Addressing the insecurity of so many communities, Christian and other, in the region – whether it is the insecurity from sadly, some local and popular, rather than governmental, pressure on Christian communities in Egypt; whether it is the insecurity of Christian communities in Iraq and increasingly because of the refugee problem within Syria itself; the insecurity of the Palestinian Christian communities caught between the upper and lower millstone of the Israeli government and pressure from Muslim extremists. We are well placed to bring to bear informed comment and this evening will enrich that informed comment and also inspire and sharpen our willingness to undertake that comment and the action that will follow from it. Thank you.

Christianity, a history in the Middle East is published by the World Council of Churches. ISBN-10: 2825414247